‘Born to dare’, ‘Don’t crack under pressure’, ‘Live for greatness’ – every brand has a mantra by which it defines itself. Swiss watch manufacture Rado, aka the self-proclaimed ‘Master of Materials’, stands by the words: ‘If we can imagine it, we can make it. And if we can make it, we will.’ But, in a world in which watch brands grapple with mineral composite fibres and dabble with concrete cases, where exactly does Rado stand? In order to find out, I hopped on a train to Boncourt and the nearby town of Lengnau, Switzerland, to discover the world of ceramic production at Rado for myself.

Long-time innovators

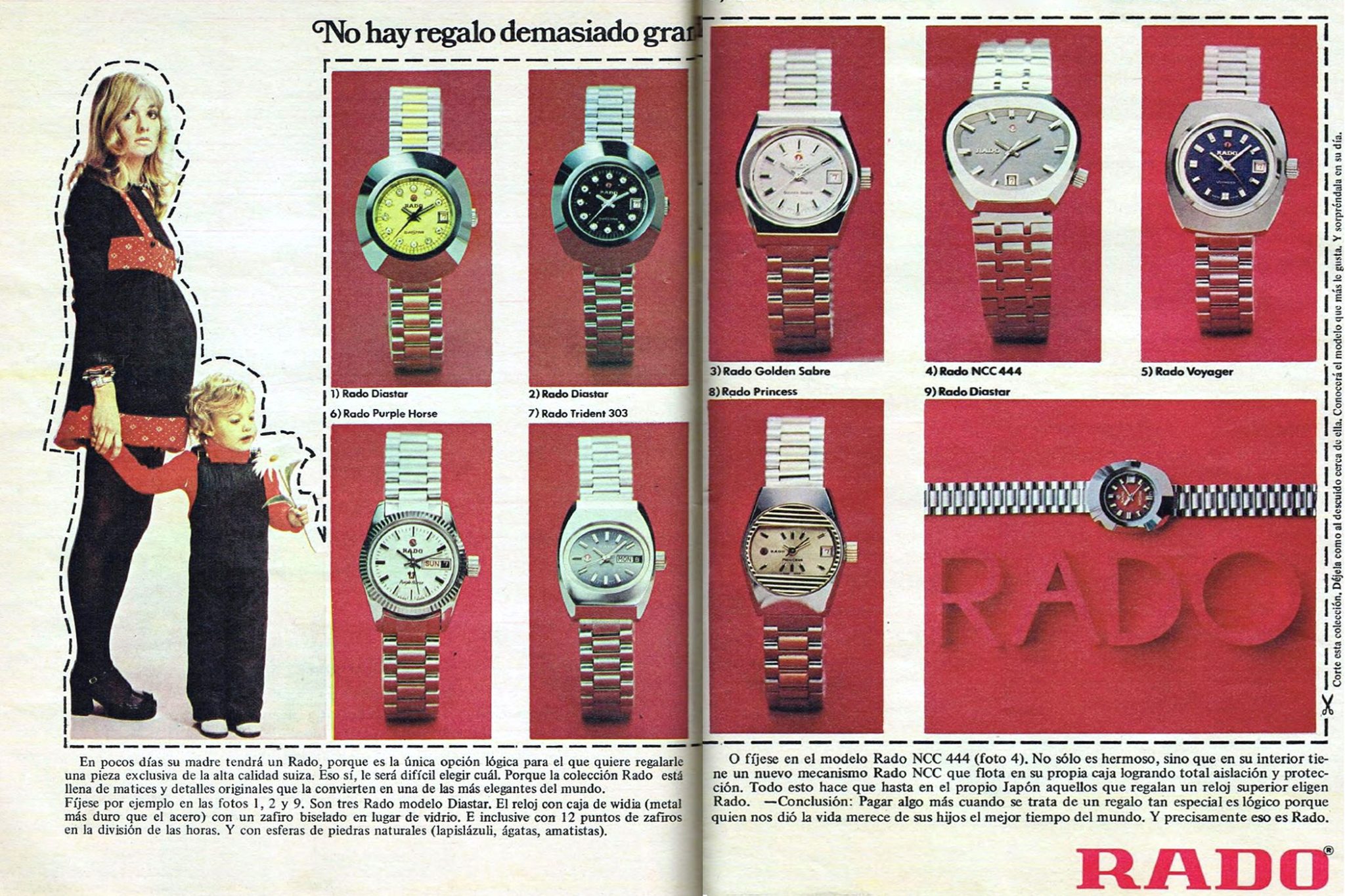

From art to technology, humanity has made use of ceramic for well over 20,000 years. Take the Venus of Dolní Věstonice, for example, which dates back as early as 28,000 BC. Admittedly, Rado’s history might not stem back quite as far, but the company’s use of ceramic has nevertheless played a pivotal role in horological history. Since its initial founding under the name Schlup & Co. in 1917 and its formation under the Rado name in 1957, when its first official collection appeared, the brand has continuously placed emphasis on pushing boundaries.

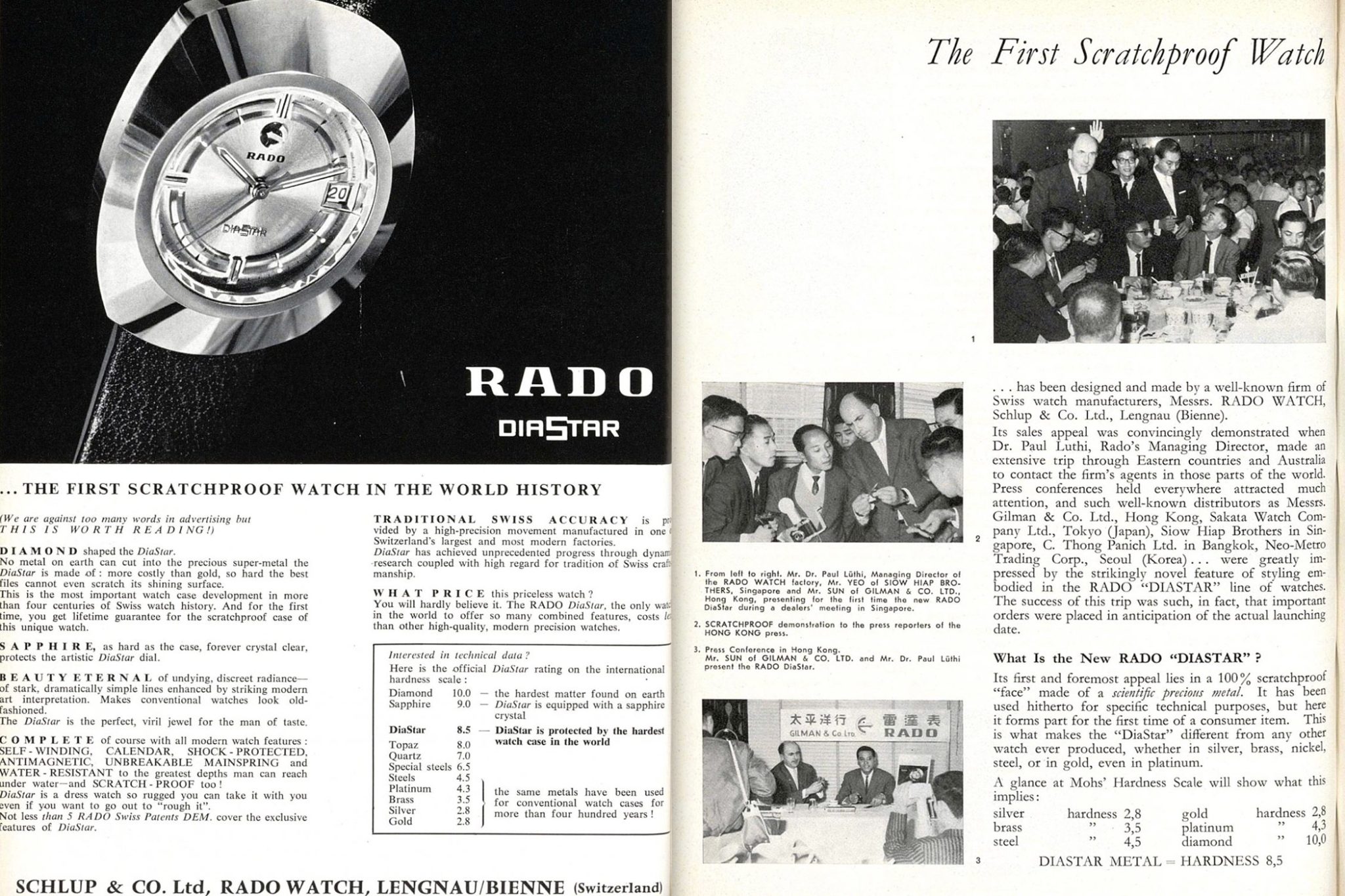

A defining moment in the history of Rado’s role as ‘Master of materials’ came in the form of ‘Hardmetal’, appearing in the DiaStar 1 in 1962 – the same year as the formative Captain Cook was introduced. As the first watch to offer both a genuinely scratch-proof case and sapphire crystal glass, the DiaStar 1 set the tone for the future of the manufacture.

This was only the beginning. Rado reached a new milestone in 1986 with the launch of its high-tech ceramic, heralding a new era in the field of ceramics. The 80s also marked the conception of Ceramos, although this material would not be officially introduced by the brand until 2011. But these ground-breaking new materials weren’t the only thing that garnered attention: the watches, with their vibrant aesthetics and metallic-looking surfaces, also won clients over with their cool, silky, tactile qualities – hence one of Rado’s other catchphrases: ‘Feel it’.

Watches should last forever – where does high-tech ceramic fit into that?

Rado is largely defined by its work with ceramics and innovations in the field – but what status does High-Tech Ceramic hold in the luxury watch industry? The answer is that high-tech ceramic actually has a number of benefits that sets it above commonly used materials such as steel or precious metals. Most notably, the material is incredibly hard, yet simultaneously light: 500 percent harder than steel, it is nonetheless 25 percent lighter. This makes it not only resilient, but also a preferable option for those who don’t like to feel much of a presence on their wrist. Likewise, Rado high-tech ceramic is ten times harder than 18-carat gold, as well as 2.5 times lighter. In addition, steel (excluding certain steel alloys dreamt up by the likes of Chopard, with their Lucent steel), is generally not hypoallergenic, whereas high-tech ceramic is not only hypoallergenic, but also adapts to its wearer’s skin temperature. Rado further increases the lightness of its ceramic watches by using monobloc ceramic cases, which forgo the need for a steel centre.

High-tech ceramic: How does Rado create it?

A trip to Comadur in Boncourt, the manufacture where Rado’s high-ceramic components are created, provided me with an insight into the production process behind the brand’s best-known material: high-tech ceramic. High-tech ceramic is, to break it down for the non-scientists amongst us, an inorganic, non-metallic material that is solidified by a firing process at high temperature. It is based on high-purity starting materials, such as zirconium oxide, aluminium oxide or silicon nitride, in powder form with a perfectly uniform grain size. High-tech ceramic has played a significant role at Rado for decades, first appearing on the bracelet of an Integral model back in 1986.

The name of the manufacture, Comadur, is a French portmanteau of ‘components’, ‘material’, and ‘durability’. Owned by the Swatch Group, the manufacture not only produces for Rado, but also, upon occasion, the other 16 brands inside the group, from Longines and Omega to Blancpain.

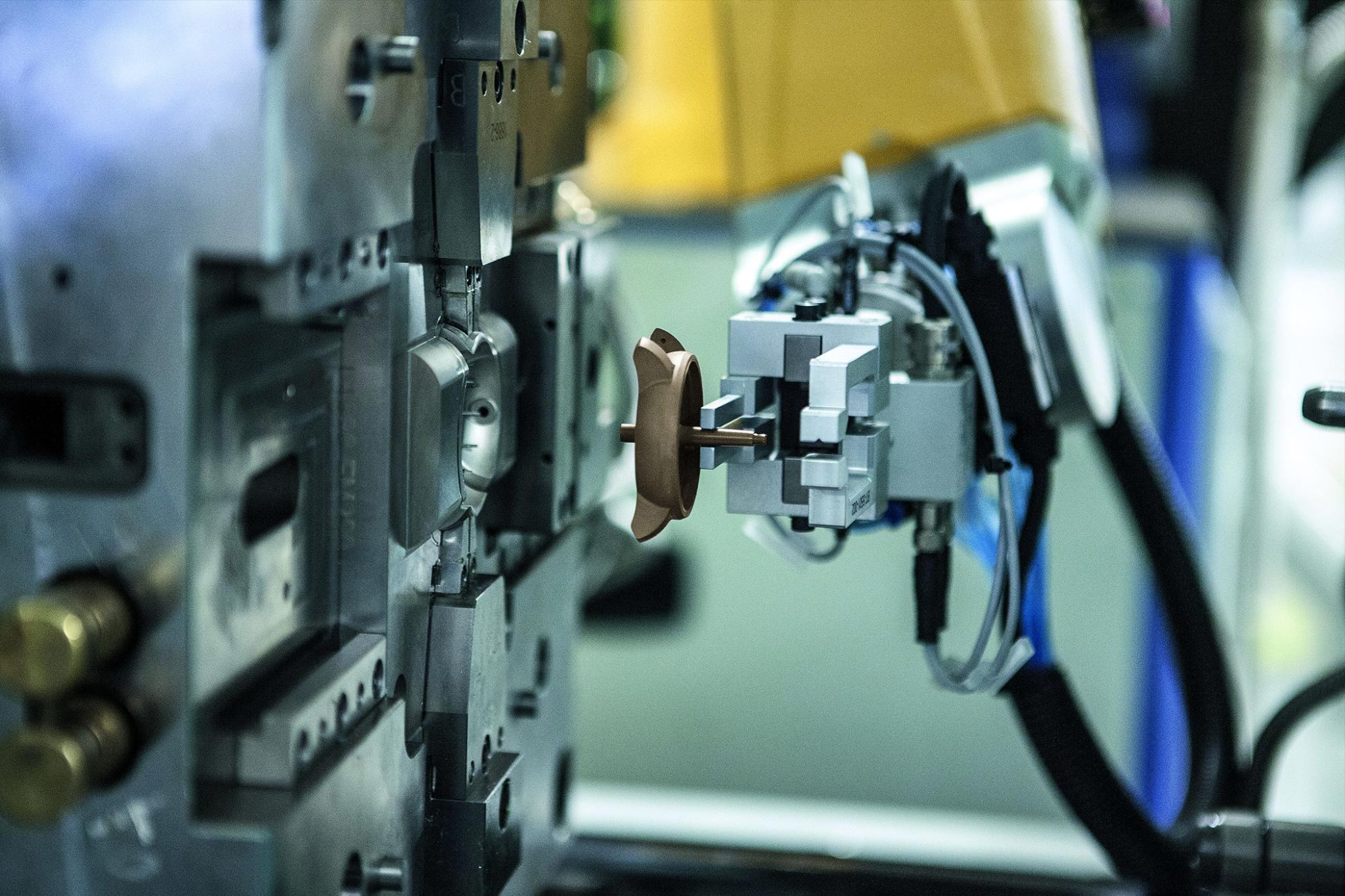

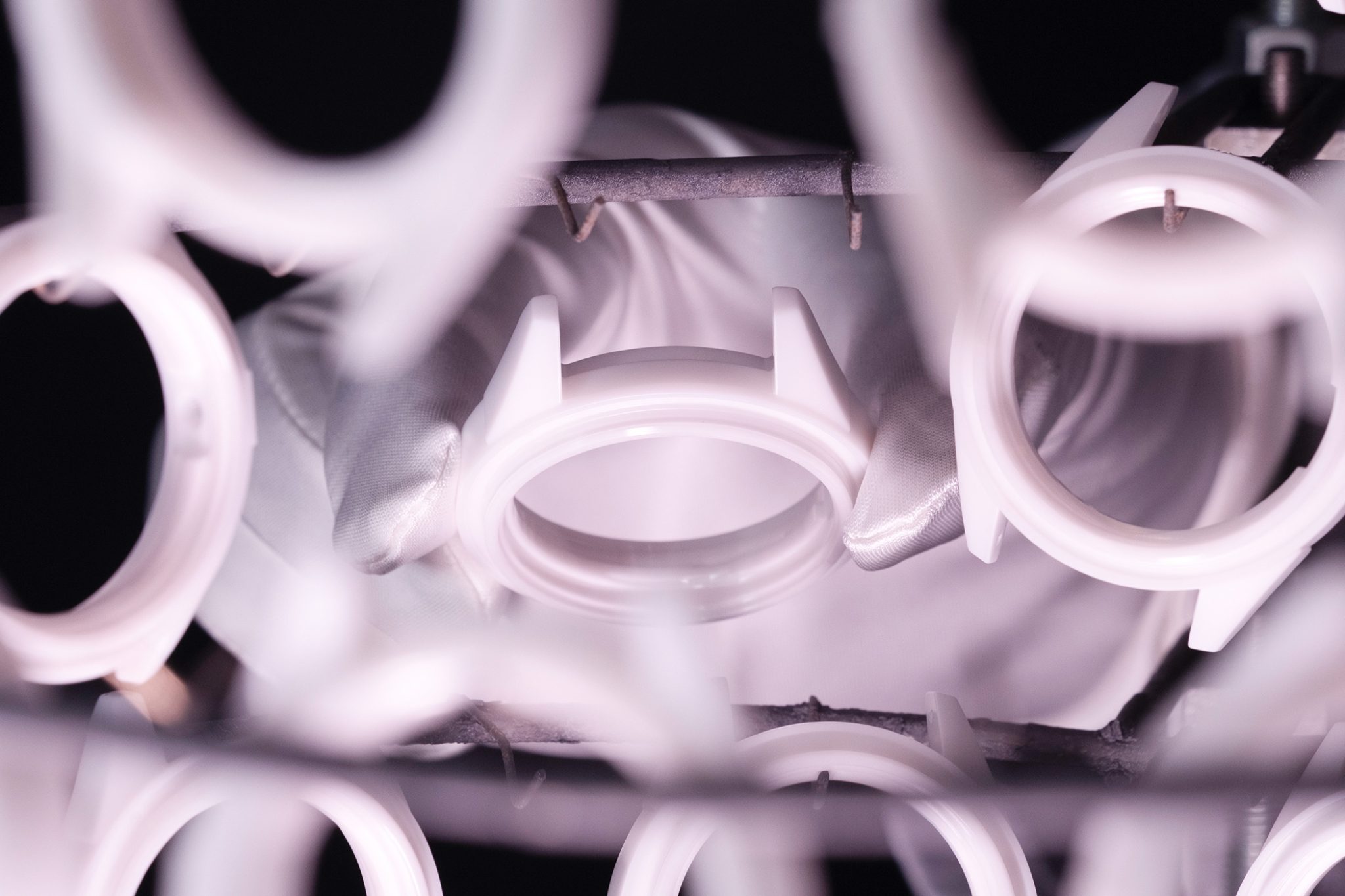

Donned from head to foot in dust-proof clothes and lab jackets, the journey into the manufacture begins with small balls (comprising of high-purity zirconium oxide powder, colourful pigments and a polymer binder), which are put into a gigantic vacuum, before extrusion and granulation can be carried out to create a thick mixture resembling playdough. At this point, the mixture can be injected into the moulds conceived by Rado’s watch designers. During this lengthy part of the production process, vital components can be created; the average Captain Cook model, for example, requires no less than 18 different moulds.

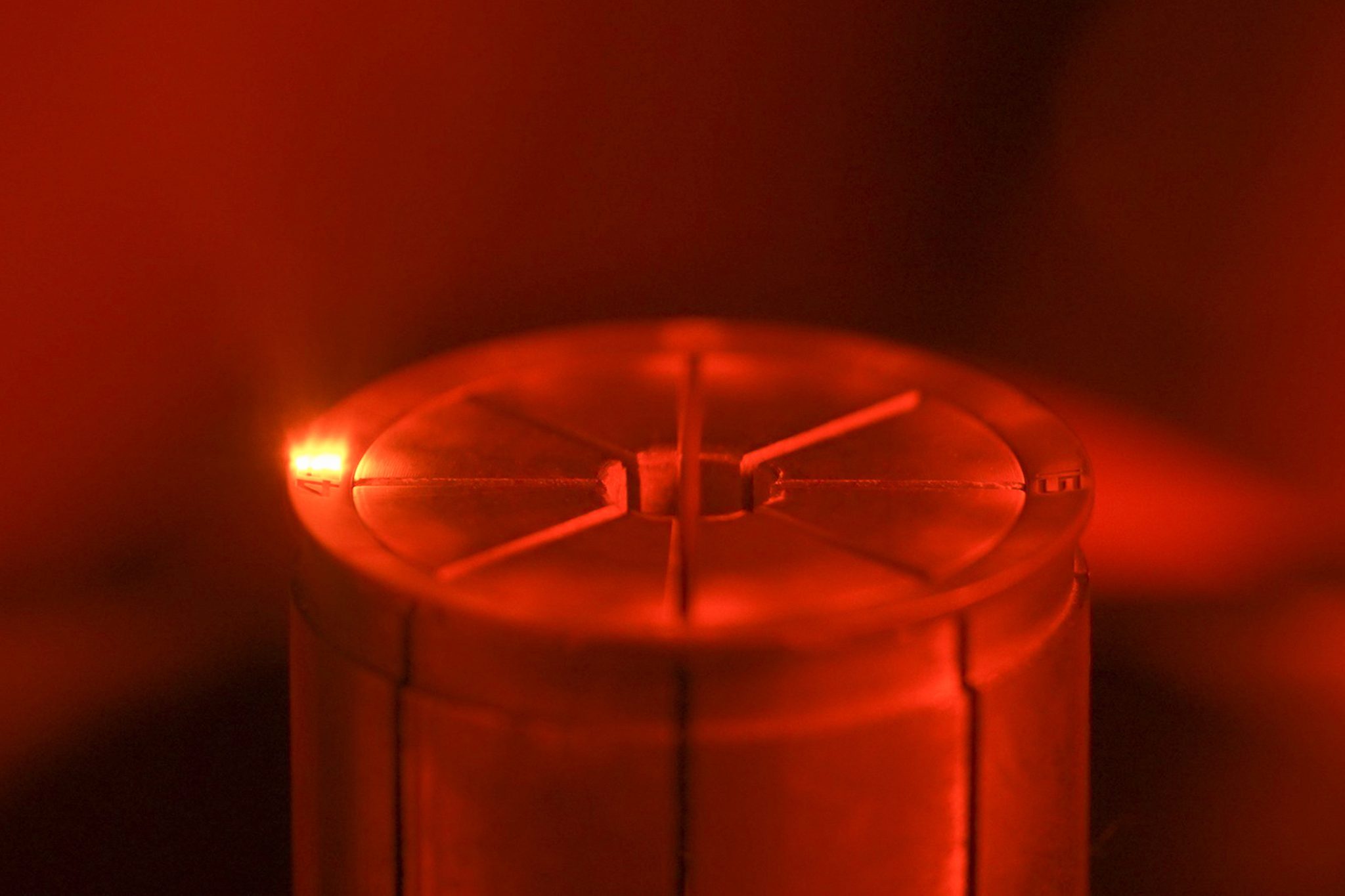

After this, the material undergoes a ‘debinding’ process (various substances are removed before sintering) that involves putting the components in alcohol so that the next step can take place: sintering. During the sintering process, the ceramic gains its hardness of 1,250 Vickers (compare that to stainless steel, which has a hardness of 180 Vickers). The pieces put into the oven, which has phenomenal temperature of around 1,450 C (although this varies slightly according to the desired colour), causing them to shrink almost 25 percent.

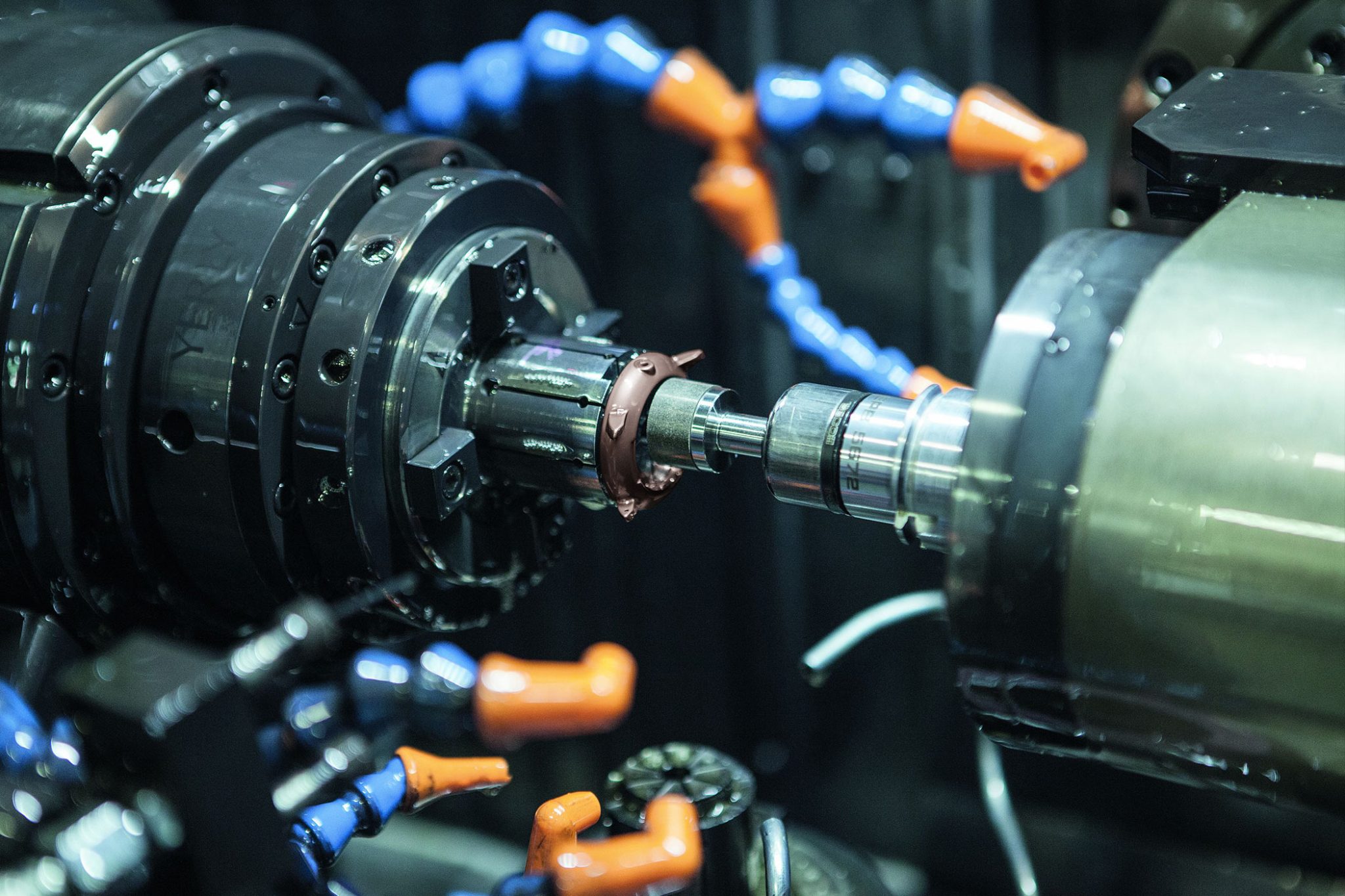

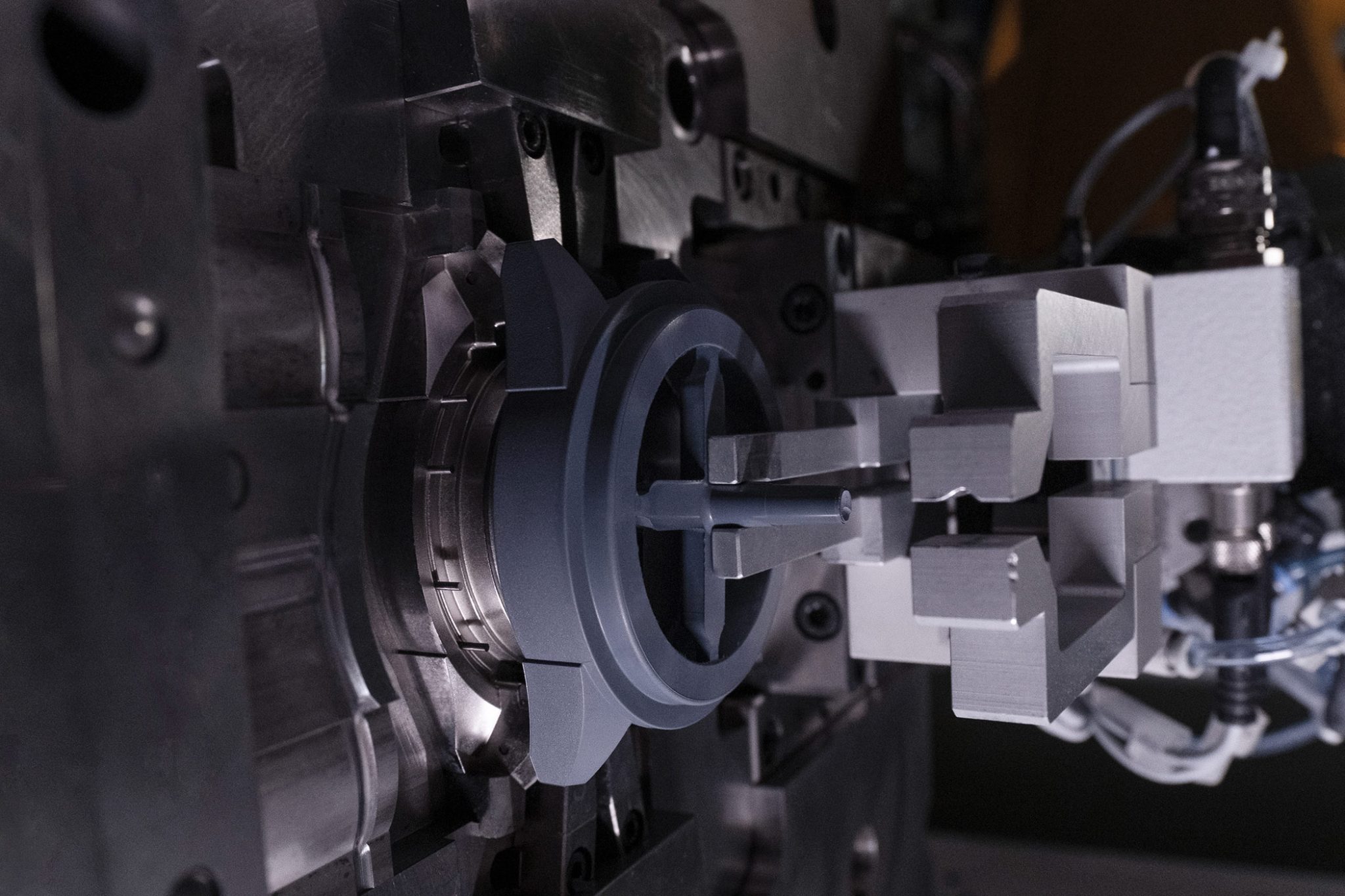

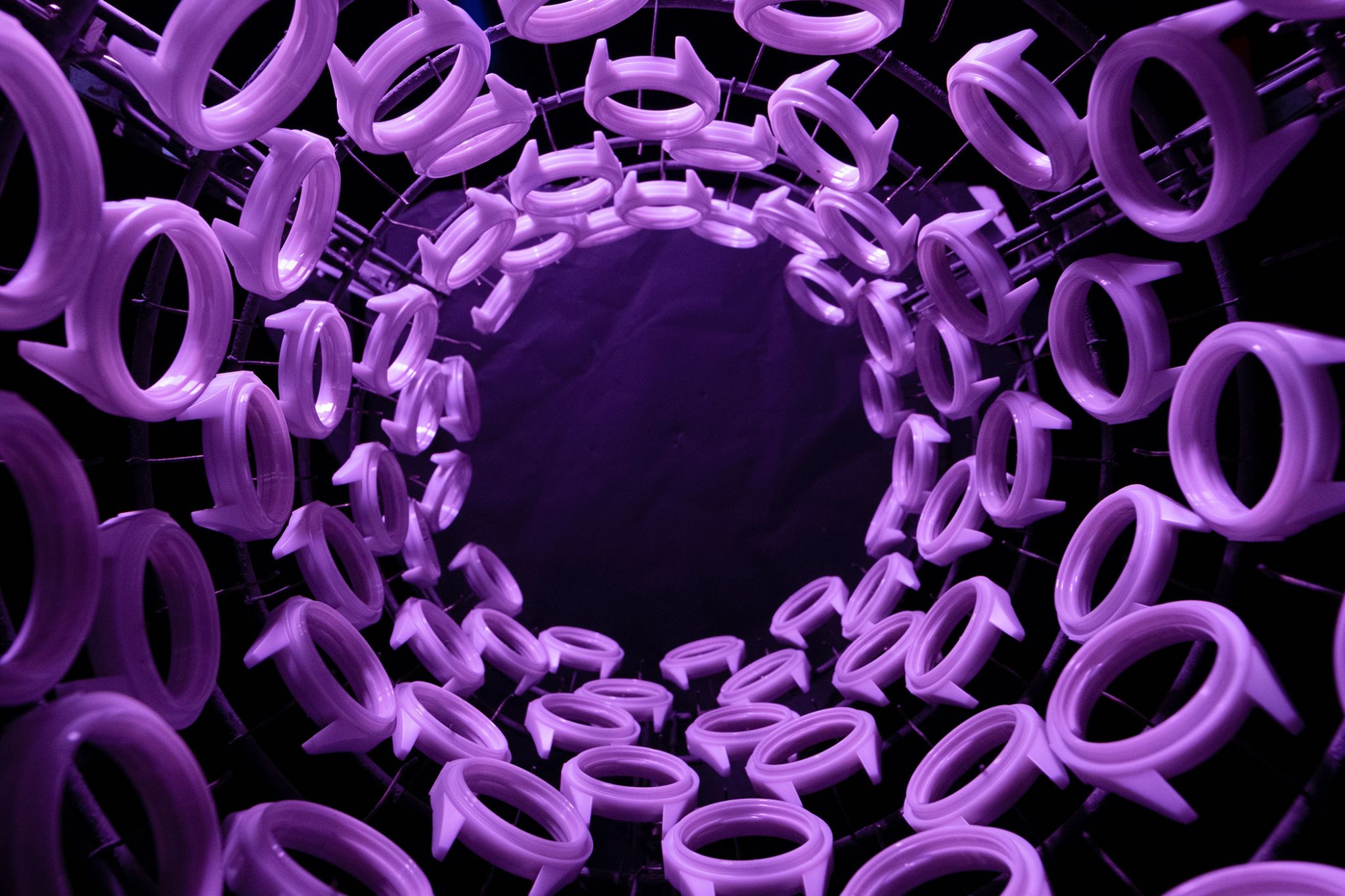

Most notably, the ceramic’s desired colour appears during the time in the oven. The true colour only appears after the sintering process is complete: for example, red is white prior to sintering, while yellow is initially grey. After the process is complete and the components are starting to resemble the finished article, the ceramic components can be machined. Given ceramic’s hard qualities, this is a complex and timely process: while steel components take only around three minutes to machine, ceramic components take one hour. Furthermore, the cases must be machined using a diamond wheel, aka a material that is harder than ceramic. Polishing the ceramic (which involves plunging the components into a churning bath of small ceramic fragments) is not much easier, with components taking one full week to complete. Then, after any engravings have been lasered onto the bezel, the lacquering of Rado watches is done by hand.

Plasma ceramic

While these steps all apply to Rado’s distinctive high-tech ceramic watches before being sent to assembly and control, a different approach is necessary to achieve the distinctive metallic colour in the brand’s plasma ceramic watches.

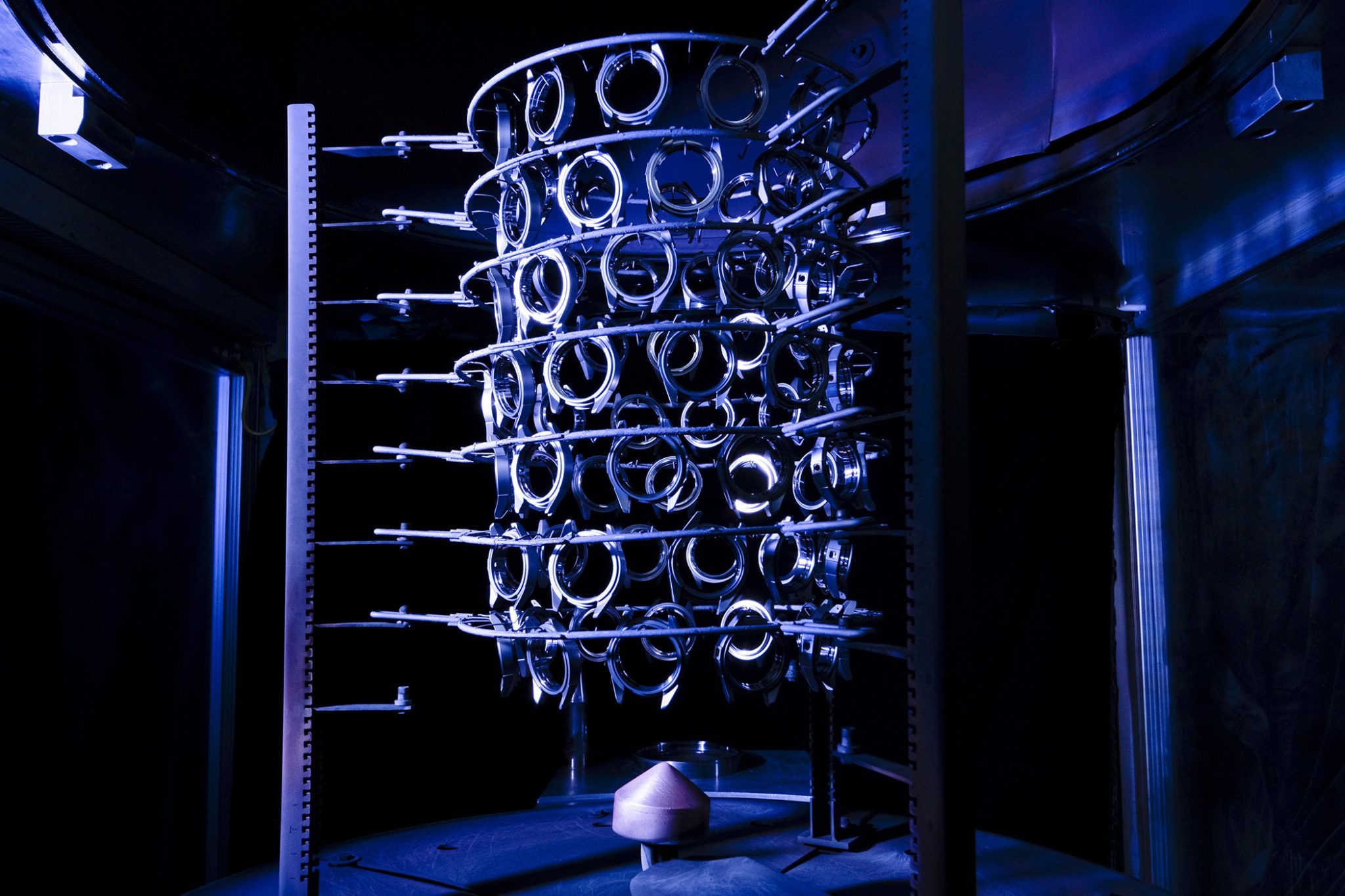

This extra step sees pre-polished white ceramic watch components being inserted into a plasma column, heated to no less than 20,000 degrees C, and remaining in the column for three hours. This ‘plasma carburising process’, which Rado has been using since the launch of the Ceramica in 1998, does change the chemical composition of the ceramic, though its properties remain unaffected. This leaves plasma ceramic watches as hard, scratch-resistant, light and hypoallergenic as any other ceramic watch produced at Rado with a very distinctive metallic appearance.

The pivotal role of the Rado Diastar 1

The Rado Diastar, aka the world’s first scratch-proof timepiece, was a ground-breaking watch within the industry, also marking several milestones for the brand. This includes the conception and implementation of materials such as Ceramos, sapphire crystal, and Hardmetal, each of which are worth looking at in more detail.

Ceramos

While plasma ceramic, despite appearances, is not a metal, Rado’s innovative composite material Ceramos does use metal, combining hard ceramic (around 90 percent titanium carbide) with the lustre of a metal alloy. This not only creates further scratch resistance, but also lowers the watch’s weight. The best known Ceramos model is certainly the Diastar Original reintroduced last year – which is a perfect model for a segue into Rado’s work with sapphire crystal, our penultimate stop on this whistle-stop tour of Rado’s journey to its title as ‘Master of Materials’.

Sapphire crystal

Sapphire crystal is one of the hardest materials known to man – yet it didn’t enter the watch industry on a large scale until deep into the second half of the 20th century, with many brands typically using plexiglass. Rado changed the luxury Swiss watch game in 1962 when it came forth with a commercial watch, produced on a large scale, in the form of the distinctive DiaStar 1 in 1962. Yet Rado’s use of sapphire crystal extends beyond ergonomics, with the brand also exploring how the material can enhance the aesthetics of Rado watches.

Firstly, Rado has specialised in ‘edge-to-edge’ sapphire crystal since 1976. While on most watches, the sapphire crystal extends as far as the bezel, ‘edge-to-edge’ sapphire crystal extends over the case. Secondly, Rado adds distinctive geometric shapes to some of its watches’ sapphire crystal. This is no easy process, with machining and grinding carefully carried out with the help of diamond tools.

Hardmetal

Hardmetal can be seen as the precursor to Ceramos: indeed, the first DiaStar introduced in 1962 used this material. Consisting of ceramic (tungsten carbide) and a metal binder, Hardmetal offers both the hardness of ceramic with the toughness of metal, as well as a high-gloss finish.

If we can imagine it, we can make it. And if we can make it, we will.’

A quick trip to Comadur barely touches the surface of Rado’s achievements in the field of materials. Numerous models have challenged standards in the industry, from pieces such as the eSenza (the first watch without a crown) and the V10K, made of high-tech diamond and offering the same hardness of real diamonds, to the collaborative True Shadow, which changes colour thanks to a photochromic lens. Evidently, the creativity and ambition of Rado’s designers know no bounds.

The decision to largely focus upon one material (high-tech ceramic) is also a crucial component in Rado’s strong DNA. Whether looking for a watch that can be knocked around without the worry of scratches, or wanting something silky smooth to the touch, perhaps much of the brand’s success also boils down to people knowing exactly what to expect from a Rado watch – a genuine vantage point in unpredictable times for consumers.

Whatever the reason, there’s no doubt that, with Rado’s ever-increasing success – not least in the fast-developing Indian market, where Rado has had a stronghold for decades – we can expect great things from a horology house that constantly strives to turn its dreams into reality. Perhaps we can all learn something from that.