Oris Aquis Date Calibre 400 is the first watch to house the new in-house movement Calibre 400 - with 5 days power reserve and 10 years guarantee.

Stephen Forsey and Robert Greubel

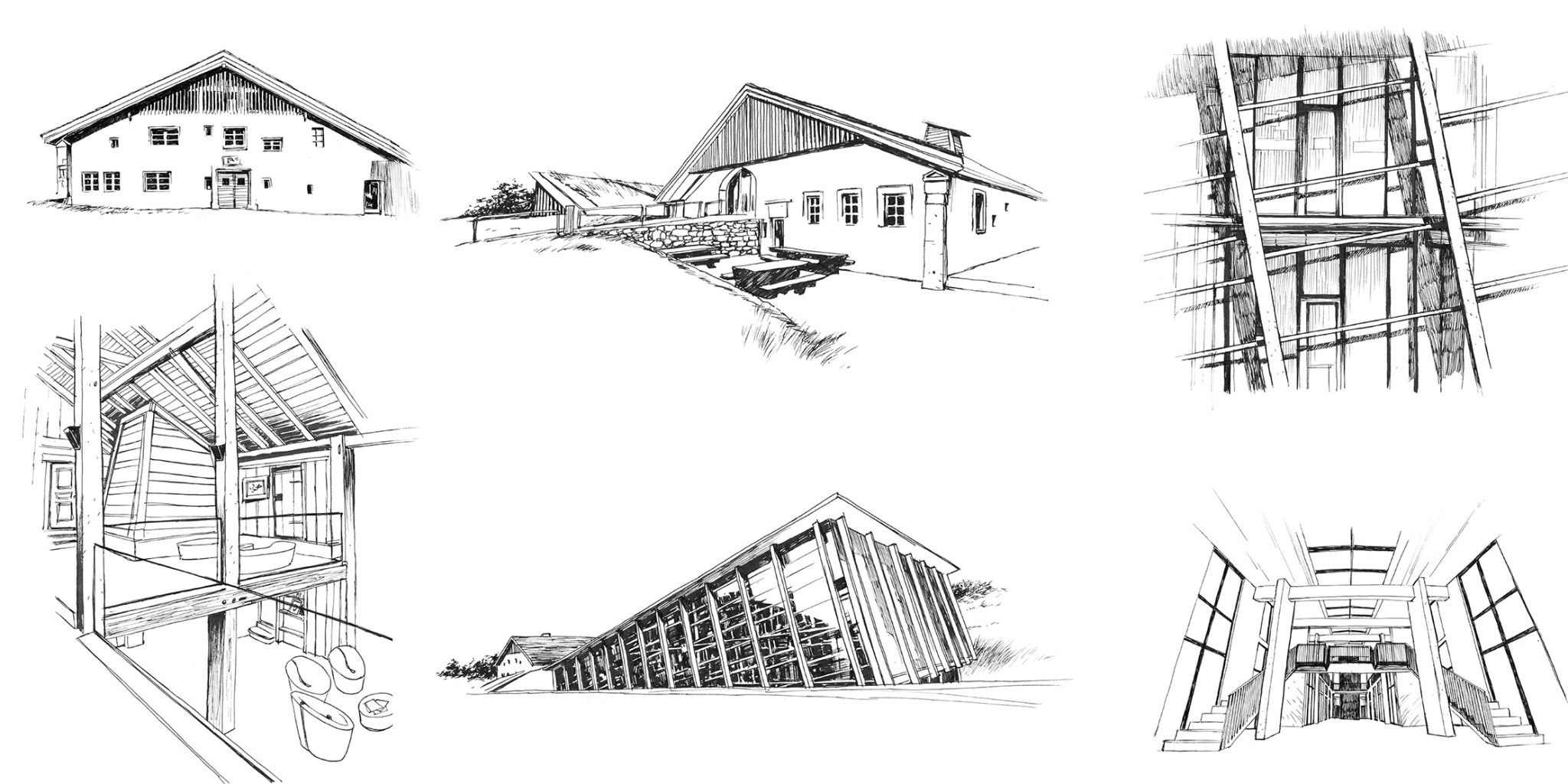

Of all the places that Stephen Forsey and his business partner, Robert Greubel, could have chosen, it is a 300-year-old farmhouse that they have picked as their place in which to carry out their mission to ensure the future of watchmaking.

The old 17th-century farmhouse

However, the old farmhouse embodies only one half of the manufacture’s philosophy, which aims to combine traditional craftsmanship with modern Haute Horlogerie. Therefore, just behind the farmhouse, stretches an avant-garde building of a kind never seen before in this quiet area of the Swiss high valley. This building is the horological heart of the Greubel Forsey watchmakers, while its adjoining farmhouse is the faithful old soul of the manufacture.

Greubel Forsey’s avant-garde atelier

Stephen Forsey doesn’t really like the term “manufacture”. He prefers to speak of a “atelier”. In 2004, he founded his watch brand together with Robert Greubel. In 2007, Greubel and Forsey bought the old 17th century farmhouse.

The farmhouse and atelier are interconnected

It is only since 2009, when the atelier was completed, that Greubel Forsey’s atelier became united under one roof: researchers, mathematicians, physicists, mechanics, craftsmen and, naturally, watchmakers. Before that, they were spread out over ten different sites throughout La Chaux-de-Fonds and the surrounding area.

Under the direction of Gilles Tissot, a local artist, the old farmhouse was renovated. It was important to preserve as many parts of the old building as possible. For example, many of the wooden beams, the fireplace, the cowshed, the wine cellar and a weathered stone sundial are original. Where cows once found shelter from the harsh Swiss winter, a small canteen has now been created for the approximately 100 employees at Greubel Forsey. In the old farmhouse parlour, there is still an old ceramic stone oven where, Stephen Forsey is convinced, clock-making was already practiced several hundred years ago. The room is now used for personal meetings and presentations.

Stephen Forsey

As beautiful and idyllic as the farmhouse may be, it naturally cannot meet the demands of today’s watchmaking. For this reason, Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey built the extension adjacent to the farm, in order to house the workshops with their specialists.

Like a mountain, the massive glass façade rises out of the earth, yet blends harmoniously and unobtrusively into the landscape, as if it were a part of it. It was designed by the architect Pierre Studer from Neuchâtel. The double windows of the imposing glass façade are designed to store and release the heat and cold in the spaces between them, so that the temperature in the atelier remains constant.

The building is designed to provide sufficient daylight, yet never to be exposed to direct sunlight – thus providing ideal working conditions for the watchmakers. The sloping roof is covered with grass in summer, which is used as grazing and food for sheep.

In summer, sheep graze on the roof

There is no way of reaching the atelier aside from through the old farmhouse. As a result, it’s almost as though each watchmaker is reminded every day that his work is based on a centuries-old tradition. When you come through the entrance into an old room, you will first notice a display with various inscriptions that appear on the cases, movement plates, bridges or the oscillating weight of Greubel Forsey timepieces: Savoir-Faire, Noblesse, Inventeurs Horlogers, Unique, Architecture, Perfection Garde-Temps or Exclusivite.

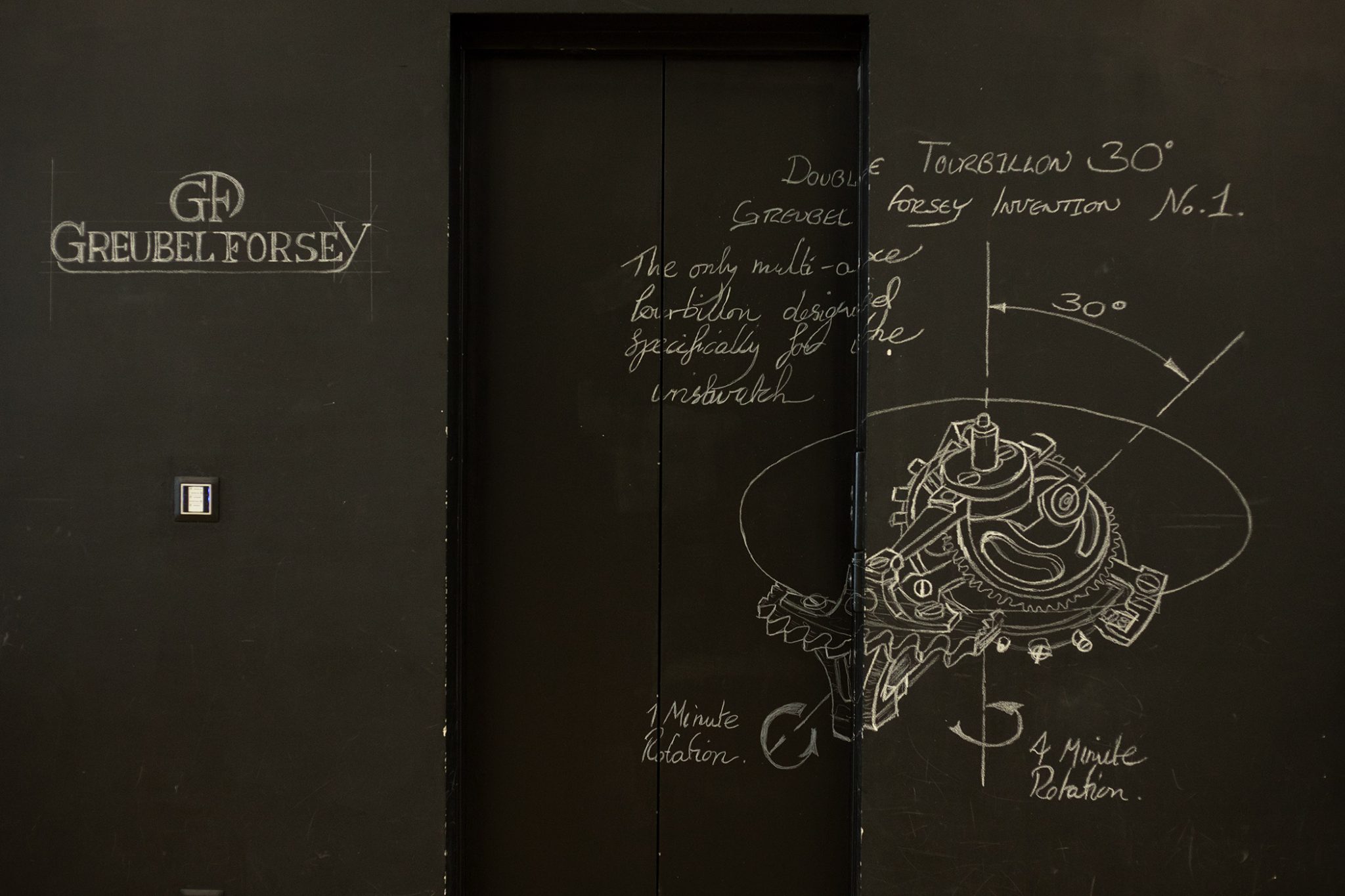

They are synonyms for the principles that the two watchmakers have been striving for across the decades. The business partners first met at Renaud & Papi, where they both worked on ultra-complex movements. There they realised that they shared the same vision, and founded CompliTime in 2001 with the aim of developing complex mechanisms for established brands. In 2004, they created their own brand, Greubel Forsey, and launched their first timepiece and invention, the Double Tourbillon 30°.

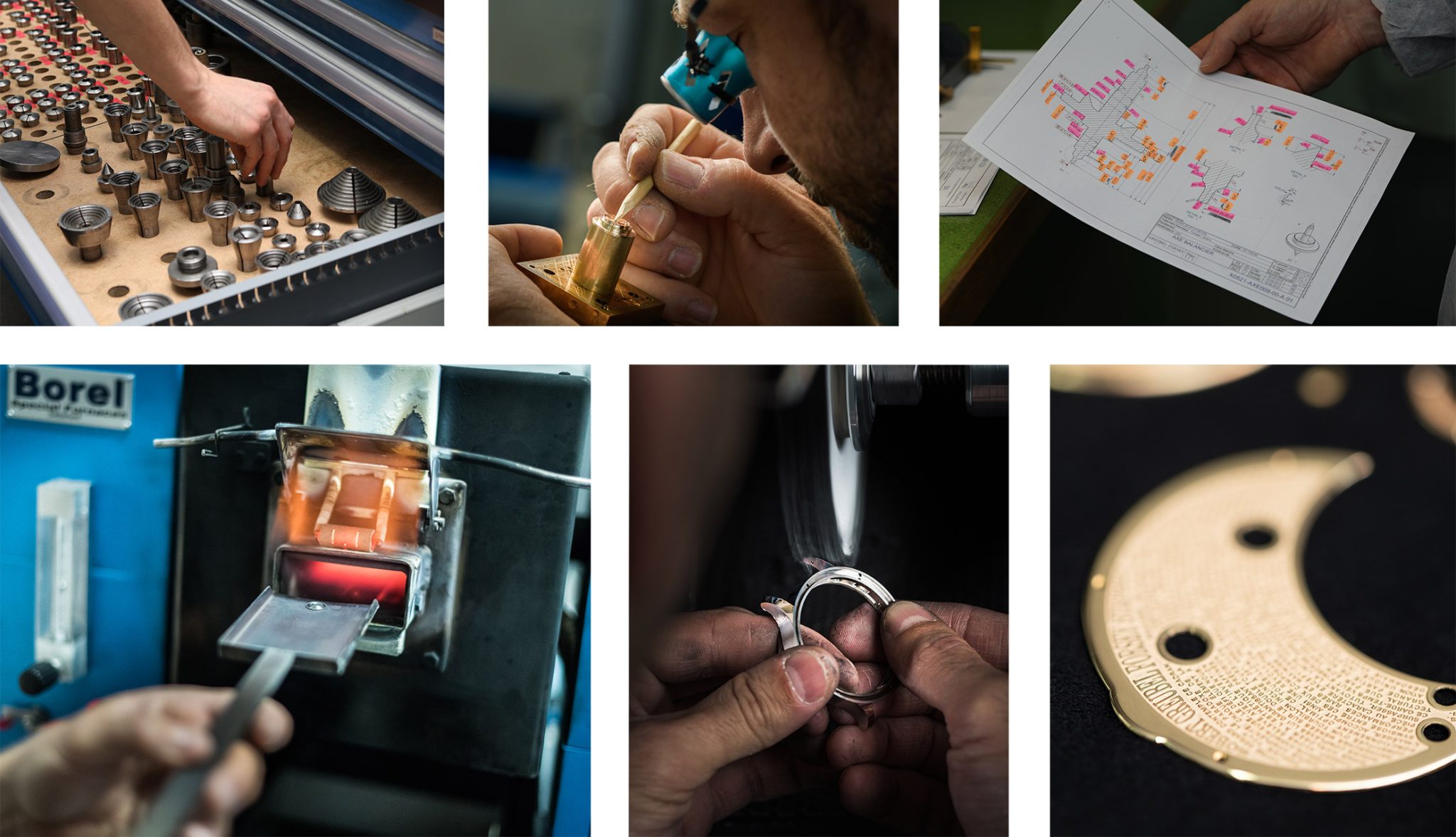

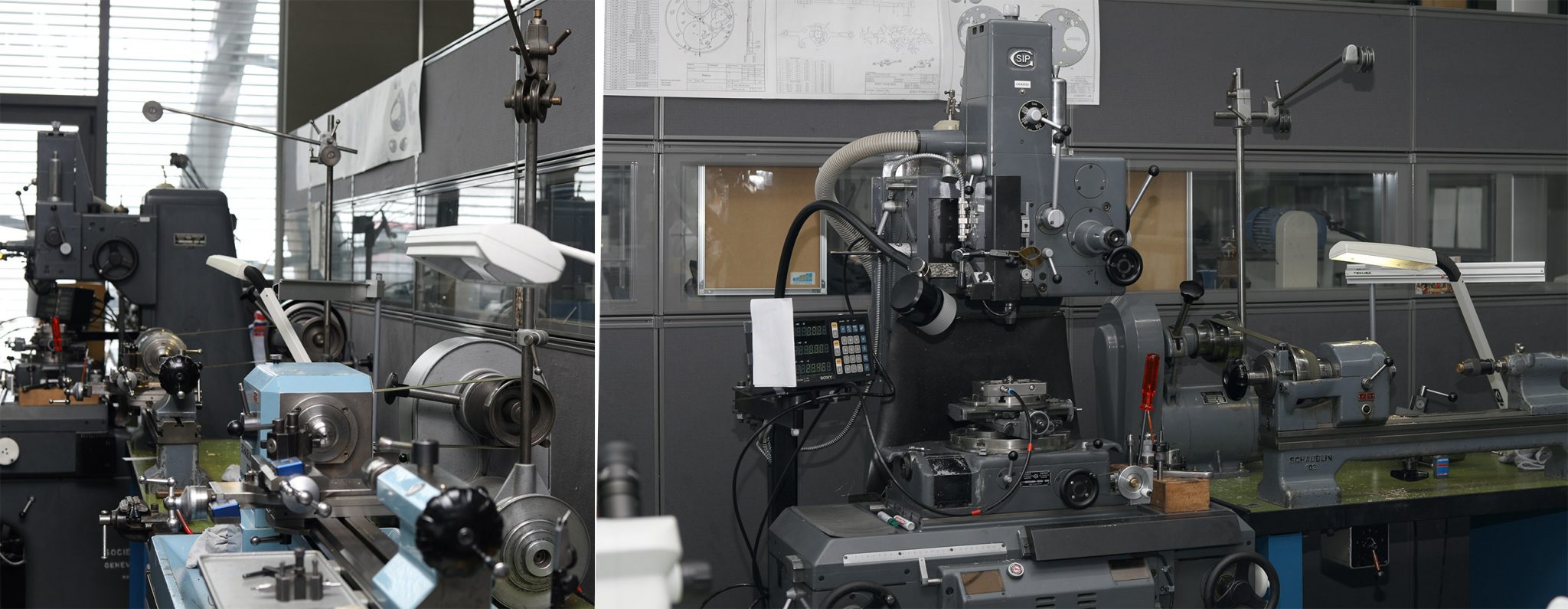

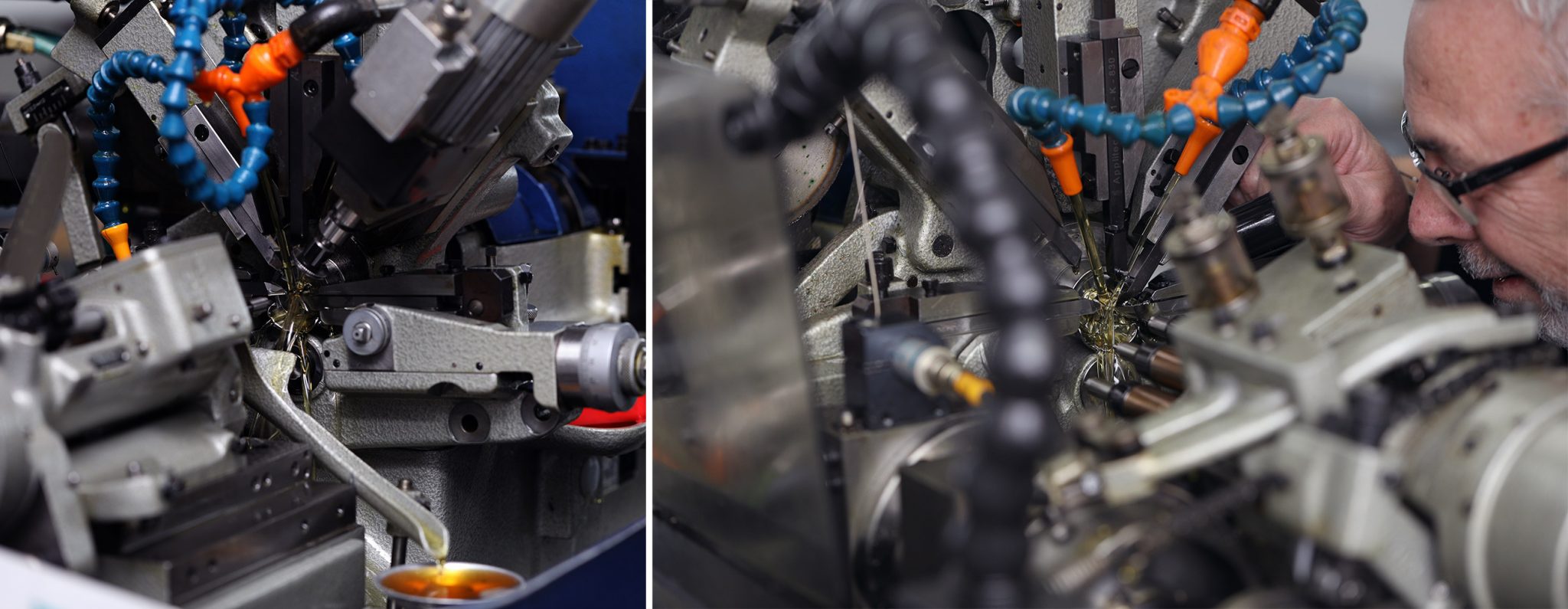

Creating a timepiece at Greubel Forsey is not about speed or the latest machines. Only about 100 timepieces are created in the atelier each year. Most of these are made by hand or with the help of machines, some of which are over 100 years old. Greubel Forsey aims to defy the increasingly industrial side of watchmaking, alternatively cultivating traditional craftsmanship in order to prevent it from dying out.

Of course, machines support the watchmakers in their work, but they are mostly operated by hand. “The machine is merely an extension of the human hand,” asserts Stephen Forsey. It takes about 10-15 years to master the old machines completely, and sometimes, it takes 50-100 times more time than working with a modern CNC machine. Nevertheless, the two watchmakers are more concerned with “keeping a craft alive than running against the clock”.

At Greubel Forsey, all movement parts are pedantically embossed, polished, finished and checked for the smallest discrepancies by only the best watchmakers. Stephen Forsey and Robert Greubel are perfectionists through and through. However, there is a bit of a contradiction in that – because with the modern machines, the tiny components could be machined much more evenly than by hand. “In the search for perfection there is no way around imperfection, because asymmetry also stands for beauty,” Forsey says. Almost all the components of the movement mechanism are made in their own workshops. Only a few parts are supplied externally.

Even if the beauty and care that goes into a Greubel Forsey timepiece is impossible not to see, a large part of its components do remain hidden from the wearer. Only the watchmaker knows how much work and time the watches contain. Therefore, Greubel and Forsey regularly invite faithful fans of the brand to their farm and atelier to help them better understand the extent of craftsmanship on site, which is no longer visible once their watch has been assembled.

From reading this far, you would think that at Greubel Forsey, time almost seems to stand still. Every single thing requires an incredible amount of patience and time. About four months pass by (depending on the model) only for the finishing and decoration of a watch’s components. Assembling a watch at Greubel Forsey takes about 10 to 20 times longer than the average watch.

Nevertheless, Stephen and Robert have developed 30 calibres in only 16 years, including seven inventions and countless patents. For an independent watchmaker of this size, this is a rapid development within a very short timeframe. For each calibre, which usually consists of between 250 and 935 components, many parts are also brand new, and individually manufactured in small quantities. From bridges and wheels, to the smallest screws, even tools have to be produced regularly at the atelier, if there are no suitable machines available.

All working areas at Greubel Forsey are located within the new building, which is directly connected to the old farmhouse. It’s a three-storey building in which a long open corridor in the middle separates the rooms on the right and left. At the end of the corridor, an elevator takes you to the two upper floors – the white chalk painting on it, showing drawings of the various tourbillons and inventions, is hard to miss. After a brief history lesson provided by the entrance to the farm, the watchmaker is reminded here that they live life in the modern day, and, more specifically, are reminded of the technical achievements possible today.

One of the largest areas is the decoration workshop. Around 25 of the total of around 100 employees are solely responsible for the finishing of the movement components, plates, bridges, dials and cases. Interestingly, there is no school where one can learn the craft applied here. The craftsmen here are not watchmakers, but rather newcomers or career changers who are interested in the craft. At Greubel Forsey, they learn everything from the bottom up, sometimes without any previous knowledge. This, of course, requires experienced craftsmen able to pass on their knowledge.

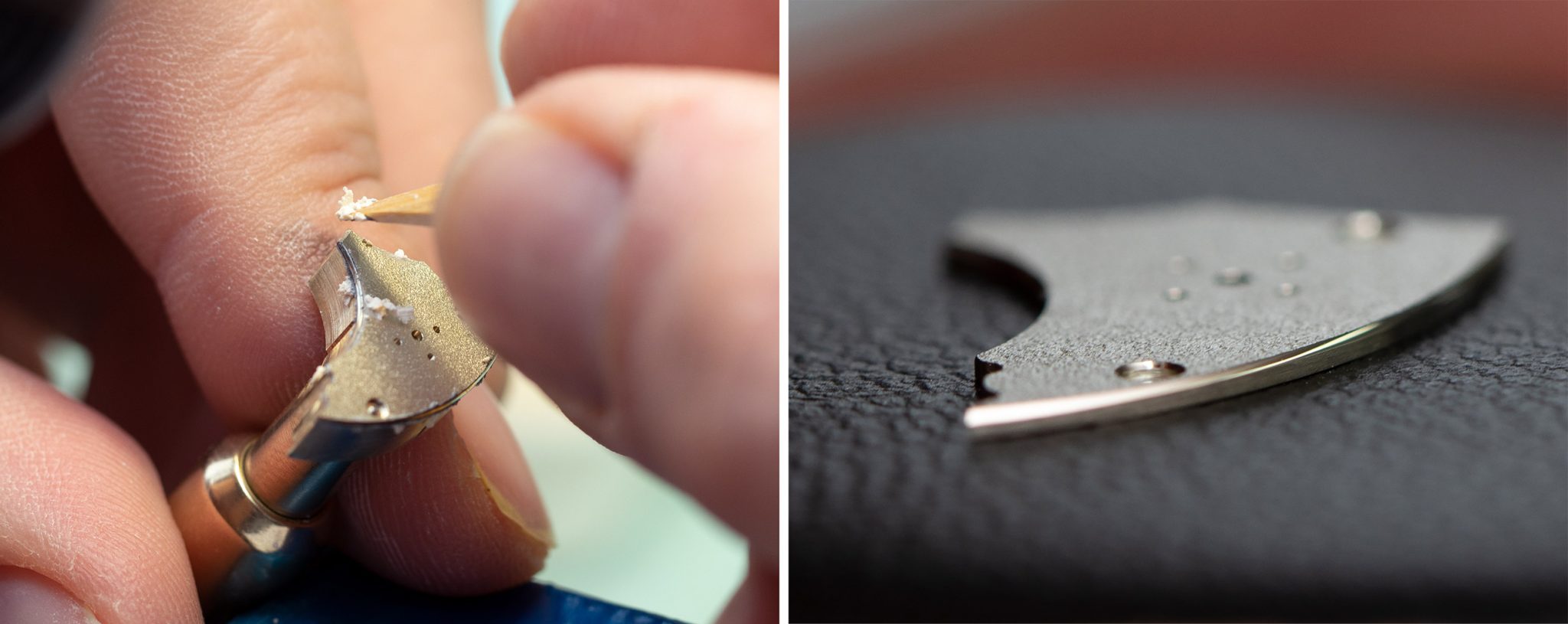

Aside from elaborate engravings, pearl cuts and polishes, “black polishing” (poli noir) is the supreme discipline of decoration, and has become a hallmark of Greubel Forsey. The surfaces are treated so carefully that light cannot reflect through tiny irregularities, and the surfaces therefore appear almost black. In the past, this method was used to protect the parts from corrosion and to remove excess material. Today, it primarily serves to add aesthetic value. As with angling, “black polishing” involves applying a paste to a wooden stick, which gives the surfaces a fine polish. For the final – and finest – polishing, a bamboo-like plant is used, which grows locally. Its surface is so fine that it is difficult to imagine that it can be used to ‘polish’ precious metals. “Alcohol is distilled from the root of the plant”, a member of the atelier staff tells us with a grin.

Meanwhile, in other rooms, designers work together with physicists and mathematicians to find solutions to the watchmaking challenges they have set Stephen and Robert – possibly the next big coup the two consequently stage. In the assembly department, a single watchmaker then assembles all of the components into a watch.

A particularly ambitious project arose earlier this year. Stephen and Robert presented Hand Made 1, a watch that was 95% handmade in the traditional way. The timepiece alone took 6,000 hours to create. Only the sapphire crystal, the case gasket, the mainspring, rubies and mainspring were not made by hand.

We can now ask ourselves the question: why go to such lengths? Is this the future of watchmaking? Well – for one thing, our human instinct tells us not to lose control of something, to the extent that it can only be controlled by robots. Moreover, it is the very sober realisation that in 50-100 years, the mechanical watch may well become a thing of the past, because knowledge will simply be lost, slowly but surely, if nobody takes action. “At Greubel Forsey, all of the traditional techniques promoted are hardly ever used nowadays,” says Forsey. After all, there are still enough people out there who appreciate real craftsmanship.

Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1

With a Greubel Forsey watch starting at 160,000 euros, you are not only investing in terms of the incredible amount of effort involved in its production – but also investing in the future of watchmaking.