From June 10th to 25th, Richard Mille will host its own regatta on both sides of the English Channel for the first time.

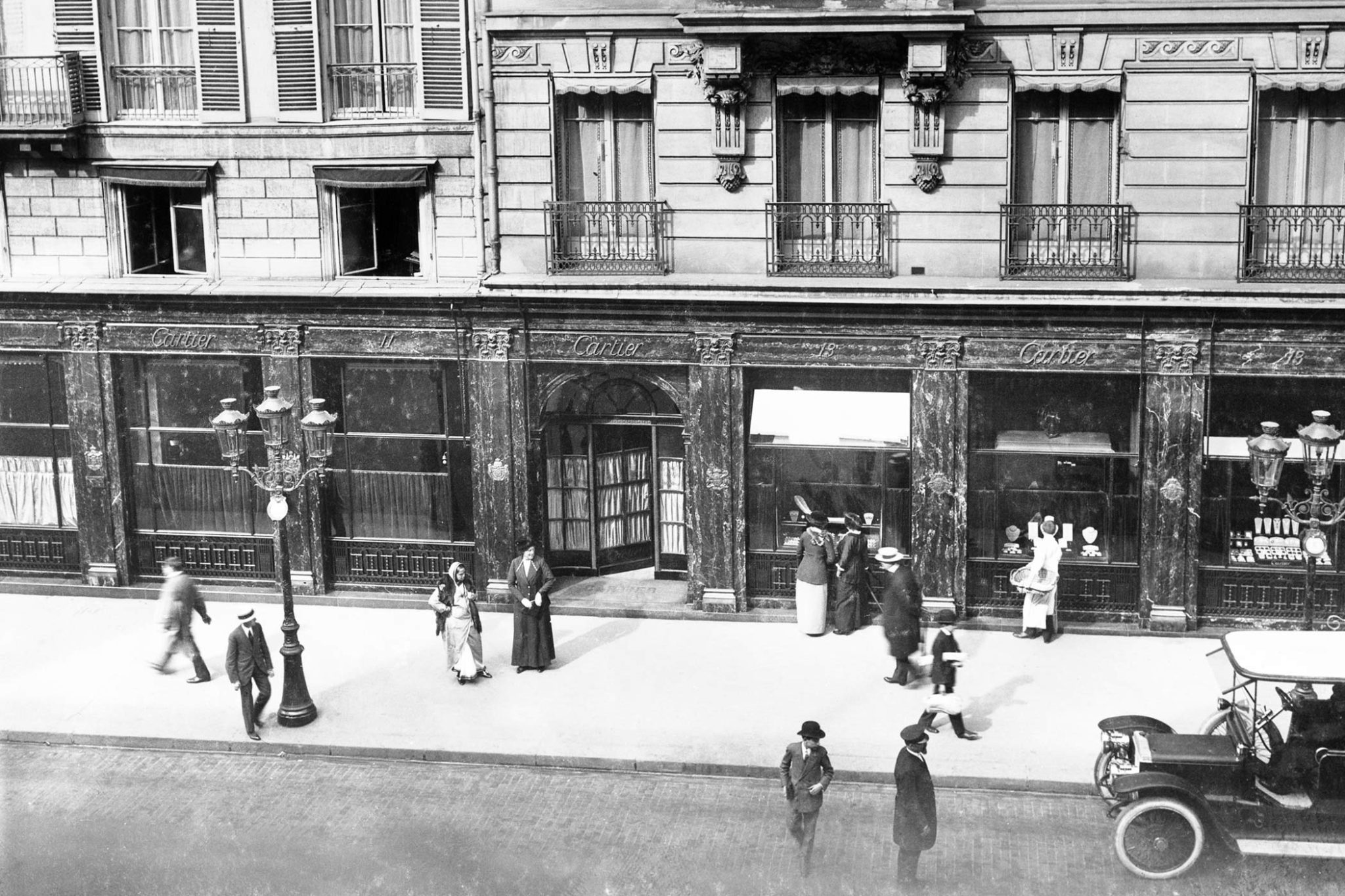

Of all the luxury brands out there, Cartier is surely the most resplendent. The Cartier insignia, glowing in gold and set against lavish red, represents decades upon decades of history, jewels, fashion, kings, queens, actresses – and, most importantly for us, watchmaking. Understatement and refinement are important: style is vital. Allow us to paint you a horological portrait of the most refined, sophisticated luxury brand on the planet.

Credit © Cartier

Jewellery, fashion and imaginative items

The year is 1847. 28-year-old Louis-François Cartier acquires a jewellery workshop from his employer in Paris, specialising in ‘jewellery, fashion and imaginative items’. Six years later, the workshop begins to sell directly to customers – and it is at this point in time, in 1853, that watches enter the Cartier books in the form of watch-brooches, chatelaines and pendants for female clients. Within two years, the brand has its first royal clients – one of whom is Princess Mathilde, cousin of Napoleon III. Cartier never was one to beat around the bush.

Louis-François Cartier (1819-1904)

Credit © Cartier

Amid the rise of the Second Empire under Napoleon III, the workshop flourishes, prompting Louis-François to open the first Cartier boutique in 1859. In the midst of the Paris uprising known as the Commune in 1871, the company is forced to temporarily relocate to London, forging the start of a relationship with a country that would go on to shape the brand’s very DNA – but more on that later. Shortly afterwards, the Cartier enterprise becomes a family business, with Alfred Cartier at the helm from 1874.

During the 1870s, against the ill-fated campaign of Napoleon III against Prussia, Cartier begins to sell miniature watches set into rings, indicating a marriage of jewellery and timekeeping within the brand. Almost two decades later, in 1888, Cartier begins to produce its very first earliest form of wristwatches. Three jewel-studded watches are available, each of which is set on a gold-link bracelet.

Credit © Cartier

In 1898, Cartier gets a new name: Alfred Cartier & fils. Louis, Pierre, and Jacques soon become Alfred’s right-hand men. As is perhaps to be expected for the time, only Alfred’s daughter, Suzanne Cartier, remains outside of the business. From the very start of his reign at Cartier, Alfred’s goal is to be international. Alfred starts by sending Pierre to Russia, to study the work of Fabergé and seek out business opportunities. Less than convinced, they soon resolve to focus on the West – though Russia and its Czars would one day become instrumental to the business.

Pierre Cartier travels to Russia

Credit © Cartier

While Pierre instead opens up Cartier to America, gaining the most elite clients from Rockefellers to Vanderbilts, Jacques takes care of expanding Cartier in London from 1902 onwards. Most crucial from a watchmaking perspective, however, are the contributions of Alfred’s visionary son Louis Cartier. Alfred brought 23-year-old Louis on board in 1898 – and he is the man who truly changes the face of Cartier’s horological faculty forever.

Alfred, Louis, Pierre and Jacques Cartier

Credit © Cartier

We must make […] articles that have a useful function […] decorated in the Cartier style.

Louis Cartier

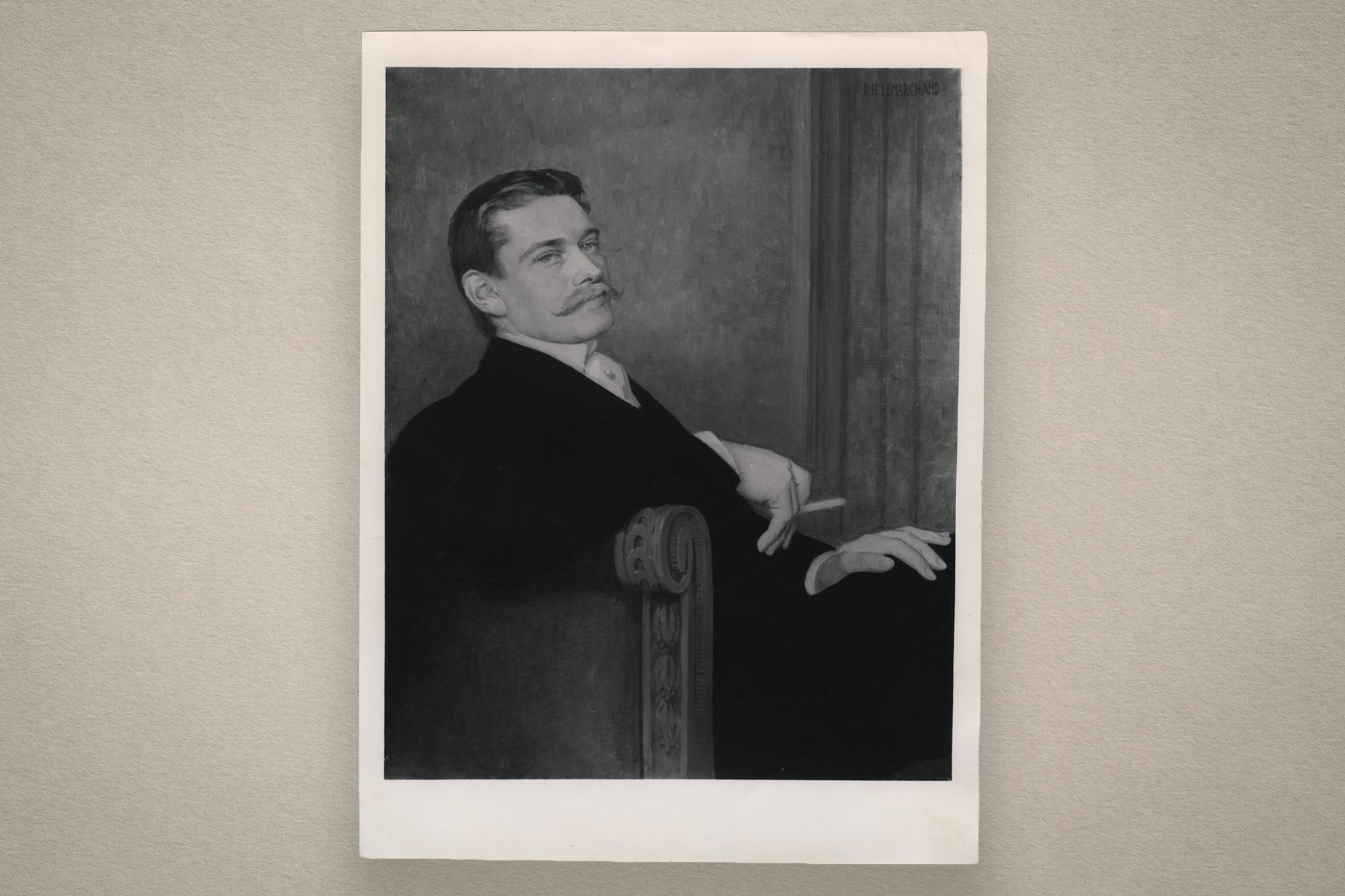

Louis Cartier (1875-1942)

Credit © Cartier

Although Cartier has a horological history dating back to 1853, it prospered most under the richly creative eye of Louis Cartier. In the early 1900s, the gentleman’s pocket watches and decorative feminine pendants used established horology houses such as Audemars Piguet and Vacheron Constantin for the movements inside. In the eyes of the Cartier business at the dawn of the 20th century, watches weren’t highly sought after; jewellery remained at the forefront of client demand. What’s more, jewellery did not require the constant tinkering, fixing, and setting inevitably demanded by watches. Thus, Cartier largely settled for creating a few specially ordered pieces created in collaboration with external watchmakers, as well as reselling externally created timepieces. This could prove lucrative enough in its own right: the maison’s records from the previous century even mention a resell of a vintage timepiece from the days of Louis XIV, as well as a couple of pieces by Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Ever the fount of creativity, it was Louis Cartier who changed this slightly lacklustre model of collaborating and reselling. He proposed a reformed watch segment model to his father, consisting of three key pillars: introduce a production workshop; reform watches into being viewed as jewellery; and support this watch production with a series of decorative clocks.

The man himself: Louis Joseph Cartier in 1898

Source: Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine

The gold and silver Cartier timepieces made (as mentioned, with external movements) up until this point had featured a few decorations: onyx, pearls, and traditional enamelling for example. In Louis’ eyes, a watch should be an item that is first and foremost beautiful: functionality should take second place. Much of the inspiration for his new timepieces, which took the form of ultra-thin ladies’ pieces, table clocks, and pocket watches, was found in Italian baroque styles promoted by Louis XIV; from wreaths, regal laurels and scrolls to Russian-inspired engine-turned decoration. Blue and green emerged as his signature colours to work with, while ‘egg clocks’ became a firm favourite of the young visionary.

1900s Cartier Egg Clock

Credit © Cartier

Platinum became an ever-more prominent material at Cartier, both in watchmaking and jewellery. In 1899, Louis sold a diamond-embedded platinum watch to the richest man in the world, American financier John Pierpont Morgan. Cartier’s timepieces were well and truly established.

By 1899, records show that Louis Cartier already had a working relationship LeCoultre, already revered for its movements. Yet Cartier also relied on several important individuals for its timepieces. From 1900 onwards, Cartier enlisted watchmakers Dagonneau, Brédillard and Prévost for their table clocks’ movements. This trio of watchmakers were also the first suppliers of movements for pocket and pendant watches. Meanwhile, a man named Joseph Vergely was the watchmaker responsible for Cartier’s distinctive gold-coin watch cases.

A diamond-set coin clock by Cartier from the early 20th century

Credit © Christies

It was Vergely who introduced Edmond Jaeger to Cartier; a decisive move that would instigate a second watchmaking revolution at the company. Having worked under Abraham-Louis Breguet himself and working as Cartier’s main supplier from 1903, Jaeger signed an official 15-year contract with Cartier in 1907, giving them exclusive rights to the vast majority of his output. This pivotal agreement gave Cartier access to an array of his inventions, from marine chronometers to his extra-thin Swiss-lever escapement movements. Jaeger’s creativity and corresponding flexibility allowed Louis Cartier to run free with his ideas, with Jaeger working on the likes of Louis’ beloved egg-shaped clocks and ball-shaped watches.

French clockmaker Edmond Jaeger (1858-1922)

Credit © Hautehorlogerie

Louis Cartier’s collaborative work with these various revered watchmakers marked another important first in the industry: the then-unique concept of a jeweller who is equally well-versed in horology, going so far as to conceive its own watches. While Cartier’s formidable line-up of watchmakers concentrated on the mechanics, Louis Cartier’s thoughts turned increasingly to designs.

The Santos was the first of Louis Cartier’s major horological conceptions, and its story is amongst the best-known Cartier legends to this day. The watch was conceived for his friend, socialite and aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont. The pilot wanted a timepiece that could be strapped to his wrist during flight, thus avoiding the dangerous need to pull out a pocket watch in the cockpit. This innovative watch might have stayed a personal secret if it had not been for the fact that socialite Santos-Dumont was something of a fashion icon in Paris – meaning what he wore was highly influential.

Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont

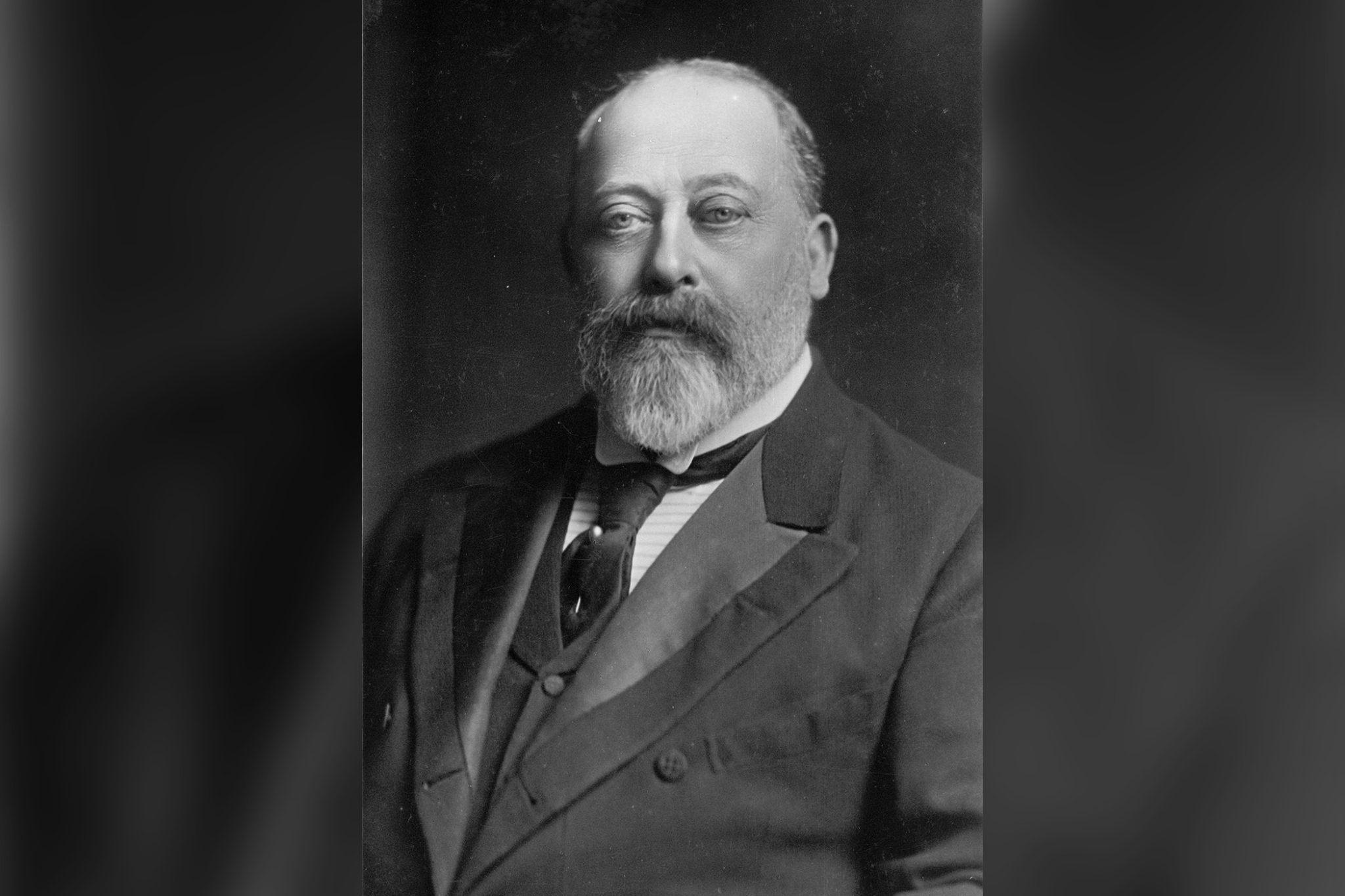

The year is 1904. Cartier London has received a Royal Warrant from King Edward VII, who later described the company as the ‘jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers’. Wristwatches are creeping into the military, but remain a fascination reserved primarily for women. Then appears a watch on a strap, conceived for Santos-Dumont, that resembles no timepiece seen before. This is the world’s first modern wristwatch for men. Cartier refer to the strap as an ‘incorporated attachment’; the term ‘strap’ is not yet in existence in this context.

King Edward VII, photographed in the early 1900s

Yet what is particularly interesting is Louis Cartier’s intuitive faith that wristwatches would catch on – long before any other maison calculated as much. By 1909, Cartier’s phenomenal watchmaker Jaeger had filed a patent for the ‘deployant buckle’, which remains a common sight securing watch straps and bracelets to this day. By 1910 – prior to the First World War, when wristwatches became more common due to necessity – Louis Cartier was creating wristwatch designs for both female and male clients of Cartier.

An early example of the Cartier Santos

Unfortunately, no trace of the first Santos watch from 1904 remains. However, the aesthetics of its 1908 successor, initially christened Santos and soon renamed the Santos-Dumont, is likely much the same. On this wristwatch, which was available commercially from 1911, we already find some of the Cartier hallmark features present today. Slanted Roman numerals; railroad minute track; cabochon crown. Legend has it that the Santos’ design aims to evoke a view of the Eiffel tower from above, in a nod to Parisians’ obsession with bird’s eye views following the invention of the aeroplane in late 1903. Ultimately, though, the Santos is known as the first ‘modern’ wristwatch because of its design’s inherent focus upon uniting the strap and case. Rather than simply using lugs to attach the strap, the rounded corners of the square case meld into the curve of the lugs.

A smart Santos model from 1912

Credit © Cartier

Many of these hallmark characteristics were transferred into Louis Cartier’s radically different Tank, featuring a movement supplied by Jaeger. Predominantly drawing inspiration from the newly conceived Renault FT tanks published in L’Illustration magazine during the First World War, the Tank’s vertical side bars evoke the caterpillar treads that flank the machine. It is odd to think that something as enduringly beautiful as Cartier’s Tank should transpire from something as terrible as war.

The then-formidable Renault FT tank

Credit © Three Lions/ Getty

Parisian Louis Cartier also likely used the prevalent avant-garde Cubism movement as his muse for the Tank, hence its strikingly simple form. As with the Santos, the straps were carefully integrated into the design of the watch – in fact, this time, the aesthetic intermission between lug and case was even smoother, with the so-called brancards (straight sides of the case) stretching straight ahead.

An early Tank model (1925)

Photocredit © Cartier

As was the case with the inadvertent advertising gifted by the chic Alberto Santos-Dumont, an early Tank prototype was quickly known for being offered up to the renowned General John Pershing, several of whose decisions proved decisive at the Western Front. The prominence of Pershing, too, pushed the geometric Tank into the world’s psyche. Other figures such as socialite and art dealer Boni de Castellane also popularised the watch in French high society, while the watch model made its Hollywood debut on the wrist of Rudolph Valentino in The Son of the Sheik – a powerful assertion to see a supposed Arabian prince donning a French watch.

Rudolph Valentino wearing his Tank in The Son of the Sheik (1926)

Credit © Phaidon

Since the introduction of the first prototype in 1917 and commercial models in 1919, with six pieces marking the start of the line, numerous models followed closely behind; most notably the Tank Cintrée in 1921 and the Tank Chinoise a year later. The first model specifically marketed towards females appeared in 1922 in the form of the Tank Allongée. In 1931, Jaeger would go onto make Cartier’s famous eight-day Tank, only needing winding one every eight days. The double-barrel movement incorporated a Swiss lever escapement, bimetallic balance, and a flat balance spring. Interestingly, though, many of these eight-day Tanks did not feature a cabochon on the winding crown – the economic depression of the 1930s did not allow for such luxuries.

Cartier ‘Kodak’ 8 Day Travel clock

Credit © Antiquorum

I don’t wear a Tank watch to tell the time. Actually I never even wind it. I wear a tank because it is the watch to wear!

Andy Warhol

Photocredit © Cartier

As with the Santos, the first men’s modern wristwatch, Louis Cartier had to somewhat convince his customers to get on board with his unusual new product. In the case of the Tank, the challenge was to demonstrate the petite Tank’s masculinity to men in particular. Interestingly, the watch was pointedly given a masculine pronoun: while in French, the word for watch uses a feminine article – la montre – the Tank watch took a masculine pronoun, making it ‘le Tank’. The Tank has proved a resounding success with men across the decades, having graced the wrists of many: from actor Fred Astaire to President John F. Kennedy, with the latter proclaiming the Tank ‘France’s greatest gift to America since the Statue of Liberty.’

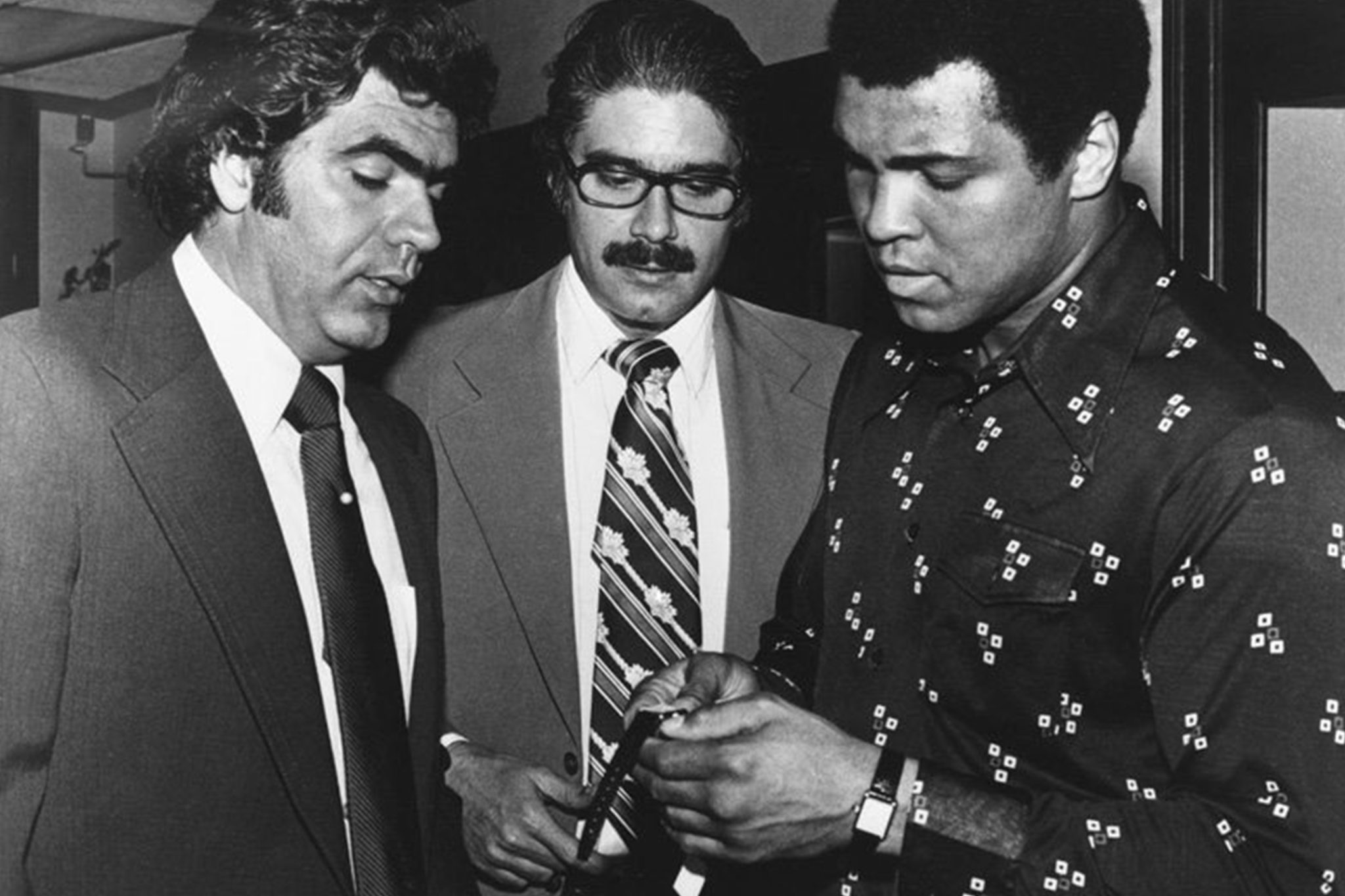

The Tank soon became the most famous unisex and ubiquitous luxury watch in the world, making it the best possible symbol of Cartier’s widespread appeal. There’s no doubt that Cartier has accompanied the world through history: from Romanovs and maharajas, to kings and politicians, it’s hard to surmise who the archetypal Cartier client is. And that’s just it: Cartier is universal.

Jacques Cartier travels to India to attend the

Delhi Durbar

Credit © Cartier

There are a few owners of the Tank, however, who stand out. Muhammed Ali is one such example; a heavyweight boxer measuring 6 foot 3 in height, who sought out elegance in a 24 mm Tank JC. By contrast, the dainty Audrey Hepburn wears a classic gold Tank in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Fast-forward to this century and, there’s Michelle Obama, famously growing up on the South Side of Chicago and rising to the dizzying heights of First Lady of the United States, who wears a Tank Française. The list is endless, with other Tank owners including the likes of Princess Diana – whose Tank was later purchased by Kim Kardashian for 379,500 US dollars –, actress Jackie Kennedy, and singer Mick Jagger.

Muhammed Ali buying his Cartier Tank in Puerto Rico, 14 February 1976

Credit © Cartier

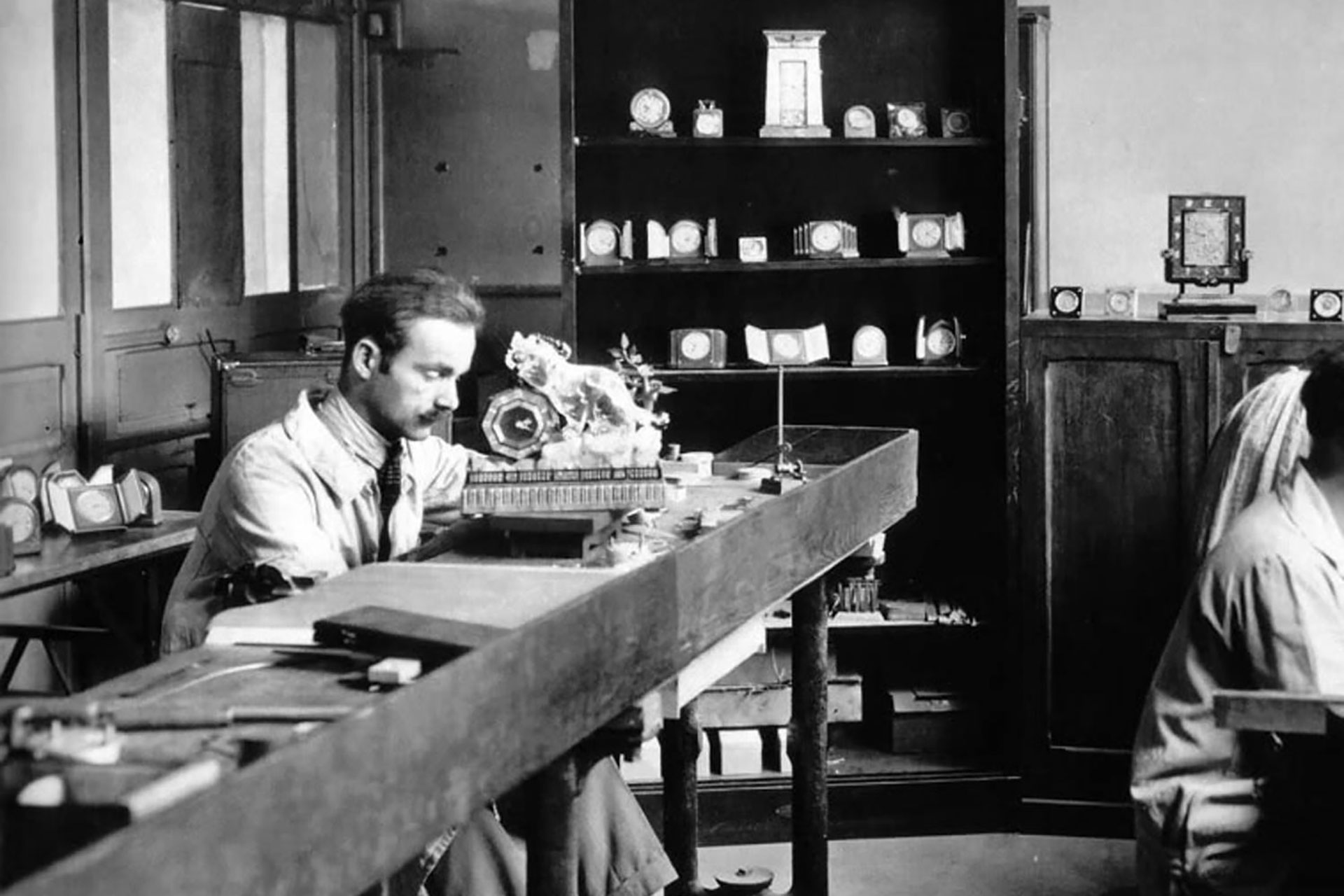

While the portfolio of Cartier watches developed ever further at Cartier in the first half of the 20th century, clocks remained an important part of the company – and the most important of these were the ‘mystery clocks’. The man responsible for these ethereal creations was Maurice Coüet. Crowned ‘miracles of timekeeping’ by one fashion magazine back in 1925, their maker Coüet was another exclusive supplier for Cartier. Coüet took much of his inspiration for these stunning horological creations from his father – an illusionist and magician.

Maurice Couet, shown in the Cartier clock workshop in 1927, was responsible for the design of Cartier’s great Art Deco clocks.

The ‘mystery’ floating clocks did not directly link the hands to the movements. Rather, they attached to two crystal discs fitted with serrated metal edges. Activated by the movement, usually housed in the clock’s base, these discs then turn the hands, one for the minutes hand and the other for the hours hand. To ensure that the illusion is perfect, the edges of the discs are concealed by the hour circle. The legacy of the clocks continue to this day; in 2022, Cartier launched the Masse Mystérieuse to much acclaim.

Credit © Cartier

The 1930s at Cartier were a time of many innovations, with the company filing handful of patents. Alongside introducing wonders such as ‘mystery pocket watches’ (an evolution from ‘mystery clocks’) and watches with interchangeable movements, there were also more important watchmaking milestones. This includes the introduction of the firm’s miniscule calibre 101 (albeit conceived by Jaeger-LeCoultre) and its first water-resistant watches.

Patents filed were largely for straps. Most significantly, Cartier patented its Vendôme strap attachment system using a central bar to put the strap on, as well as a strap that engaged not with the lugs, but rather with the bezel. Additionally, Cartier patented a method for setting a watch movement into cufflinks.

As Edmond Jaeger’s contract with Cartier came to a close, the 1930s also saw a shift away from Cartier’s close relationship with Jaeger-LeCoultre. While still a supplier, Cartier also turned to the likes of Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet, and Piaget. Fully independent watchmaking at Cartier lay still some way in the future.

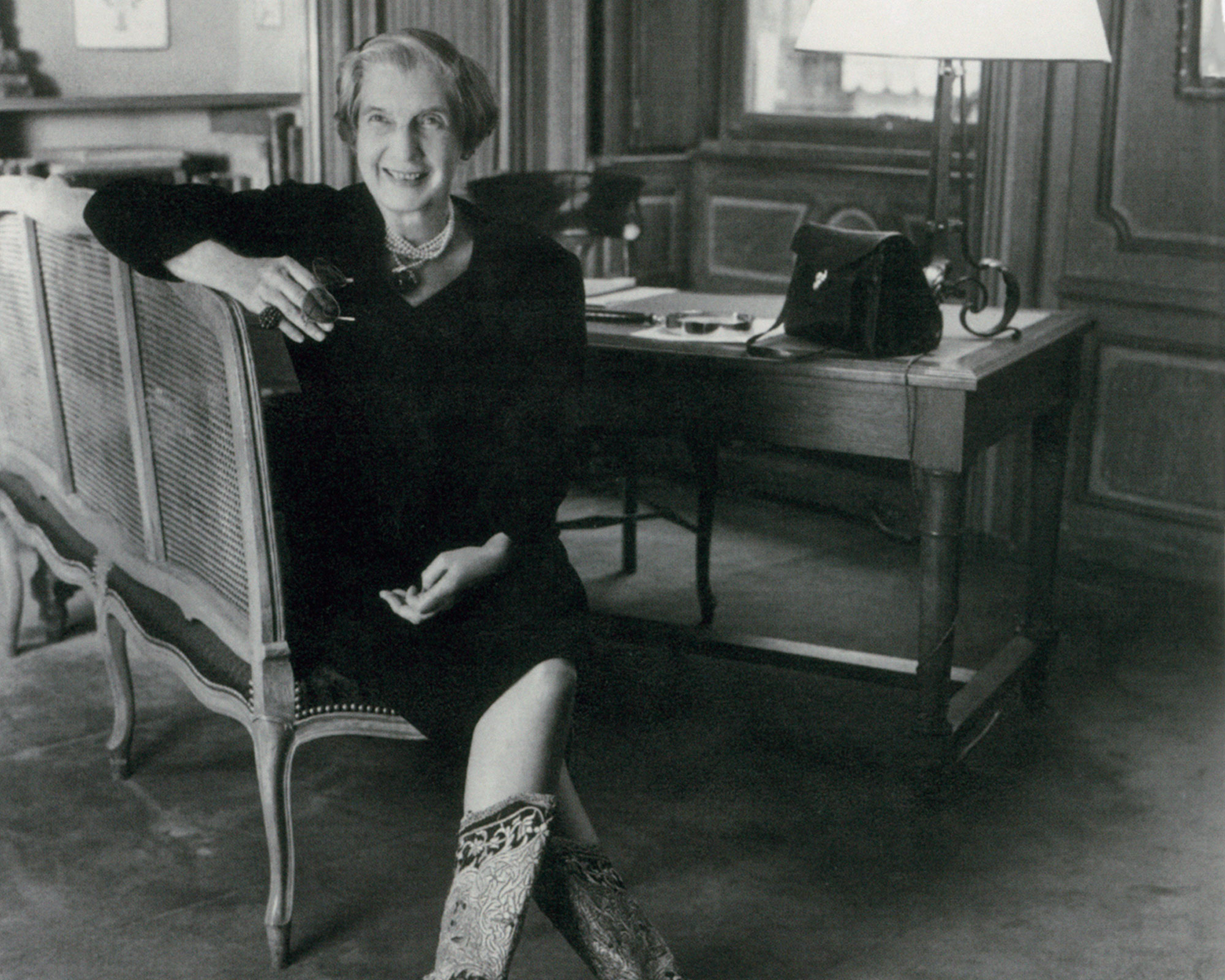

In 1941 and 1942, Jacques Cartier and the dynamic Louis Cartier passed away in quick succession, while Pierre Cartier retired soon after the war. The family-run era of business at Cartier drew to a close. Yet one important common thread from the time remained: Jeanne Toussaint. Toussaint started life at the company as the girlfriend of Louis Cartier, where he put her to work in the handbag, accessories and objects department. Thanks to her close relationship to Louis, she gained much knowledge about precious stones, settings, and technique, while she, in turn, imparted her endless creativity and natural sense for increasingly prevalent Art Deco trends, from vivid and sharp-edged looks to stylised geometric patterns.

Jeanne Toussaint (1887–1976)

Credit © Cartier

Promoted by Louis Cartier to head of the Fine Jewellery department in 1933, Toussaint also had a large impact on watchmaking at Cartier. Overseeing an entirely male workforce of designers, gem-setters and craftsmen, the creations from this time have become some of the most collectable Cartier pieces in history. Toussaint experimented with use of gold, most notably by introducing flexible gold ‘gaspipe’ tubing for use on wristwatches as well as in jewellery in the 1930s and 40s. Moreover, and more enduringly, she instigated the return to Cartier’s hallmark natural motifs of animals and flowers.

The Cartier Fabuleux Envol d’un Phoenix watch

Credit © Cartier

One motif in particular came to represent the maison: the panther. The panther image had existed under the radar at Cartier since some time, with the first panther-spot wristwatch with diamond setting appearing as early as 1914. One beloved object in her possession was a Cartier vanity case, gifted to her by Louis in 1917, featuring a panther prowling between two cypress trees. Yet Touissant’s eponymous nickname, ‘the panther’, is said to stem from Louis Cartier himself, who called her his petite Pantheré in a reference to her full-length panther fur coat.

Touissant’s panther case and the first watch with panther-spot from 1914

Credit © Cartier

In 1948, Touissant created the first Cartier La Pantheré jewel for the woman who would inadvertently bring down the British monarchy, Wallace Simpson. Causing a stir amongst Europeans and Americans alike, numerous rings, pendants, and earrings followed – and the motif remains to this day.

The La Pantheré jewel for Wallace Simpson

Credit © Cartier

The ergonomic yet elegant Pantheré de Cartier watch would not be introduced until 1983. Its introduction wholly reshaped the concept of a jewellery watch, featuring a dainty bracelet with curved links and a case with rounded corners. Elsewhere, Cartier’s Métiers d’Art makes rare panther watches using incredibly specialised techniques to this day.

The Ballon Bleu Panthere Granulation

Credit © Cartier

When it comes to the 1960s and 70s, the Cartier designers in London can take much of the credit for the defining pieces that emerged from the company’s watchmaking scene. Prior to this period, Cartier had imported its watches from Paris, but this was to change under Jean-Jacques Cartier, the son of the late Jacques who had founded the London branch. He increased his workforce and its workspaces, while also giving his employees increased autonomy – thus allowing for bolder, more contemporary pieces than ever to emerge.

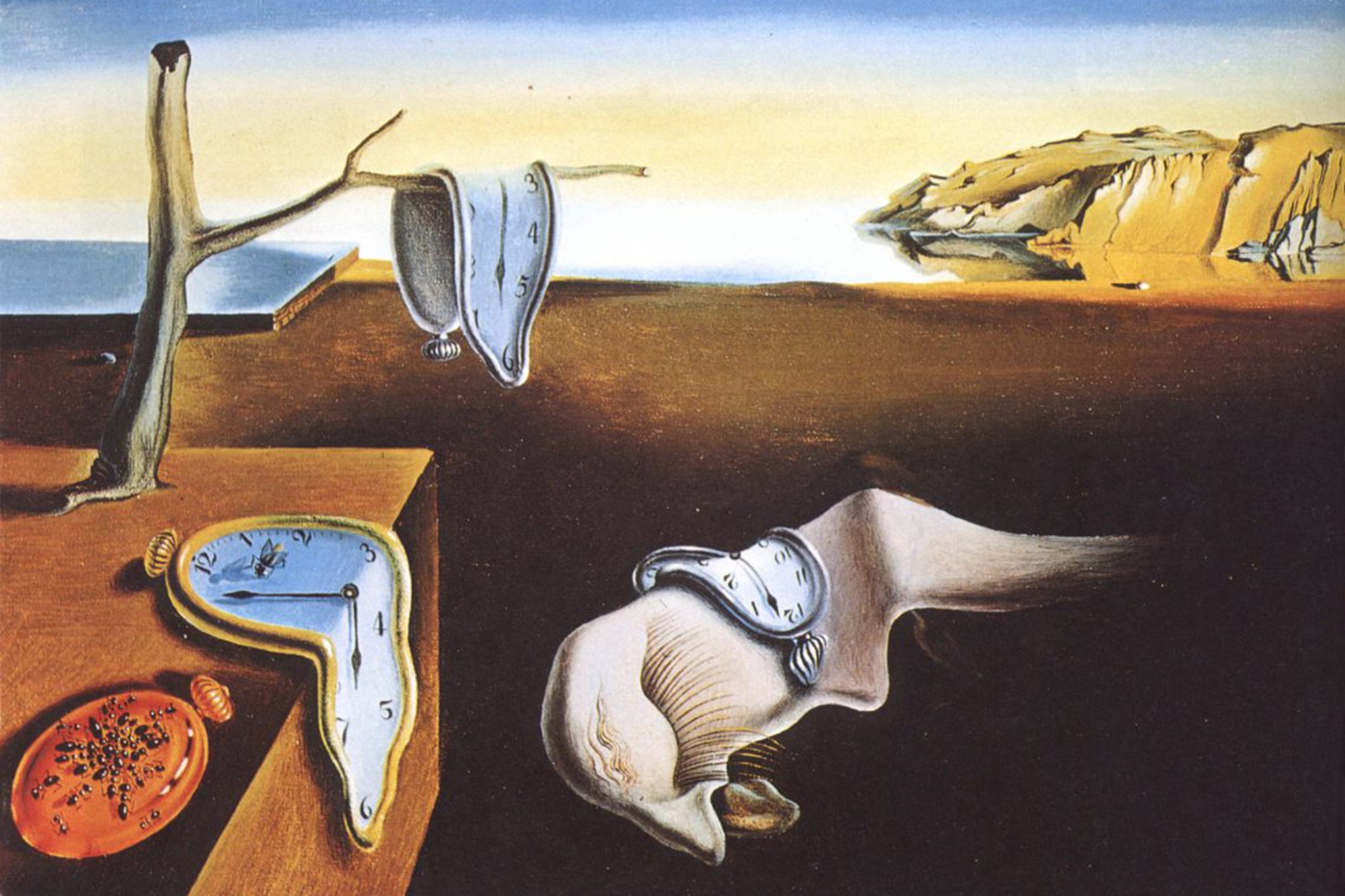

The most important example of this burst of creativity and experimentation is the exuberant Crash watch. The artistic inspiration behind Jean-Jacques and his design confidante Rupert Emmerson’s design for the Crash is not exactly known, but there are some contending theories. One is that designers took inspiration from a half-melted Cartier Maxi Oval (the Baignoire Allongée) – ovals had become an increasingly favoured shape at the maison – damaged in a car crash.

The original Cartier Crash sketch

Credit © Cartier

An alternative – and perhaps more probable – legend has it that Cartier’s creative conception was spurred by Salvador Dali’s pocket watches in his surrealist painting The Persistence of Memory.

Photocredit © Salvador Dali

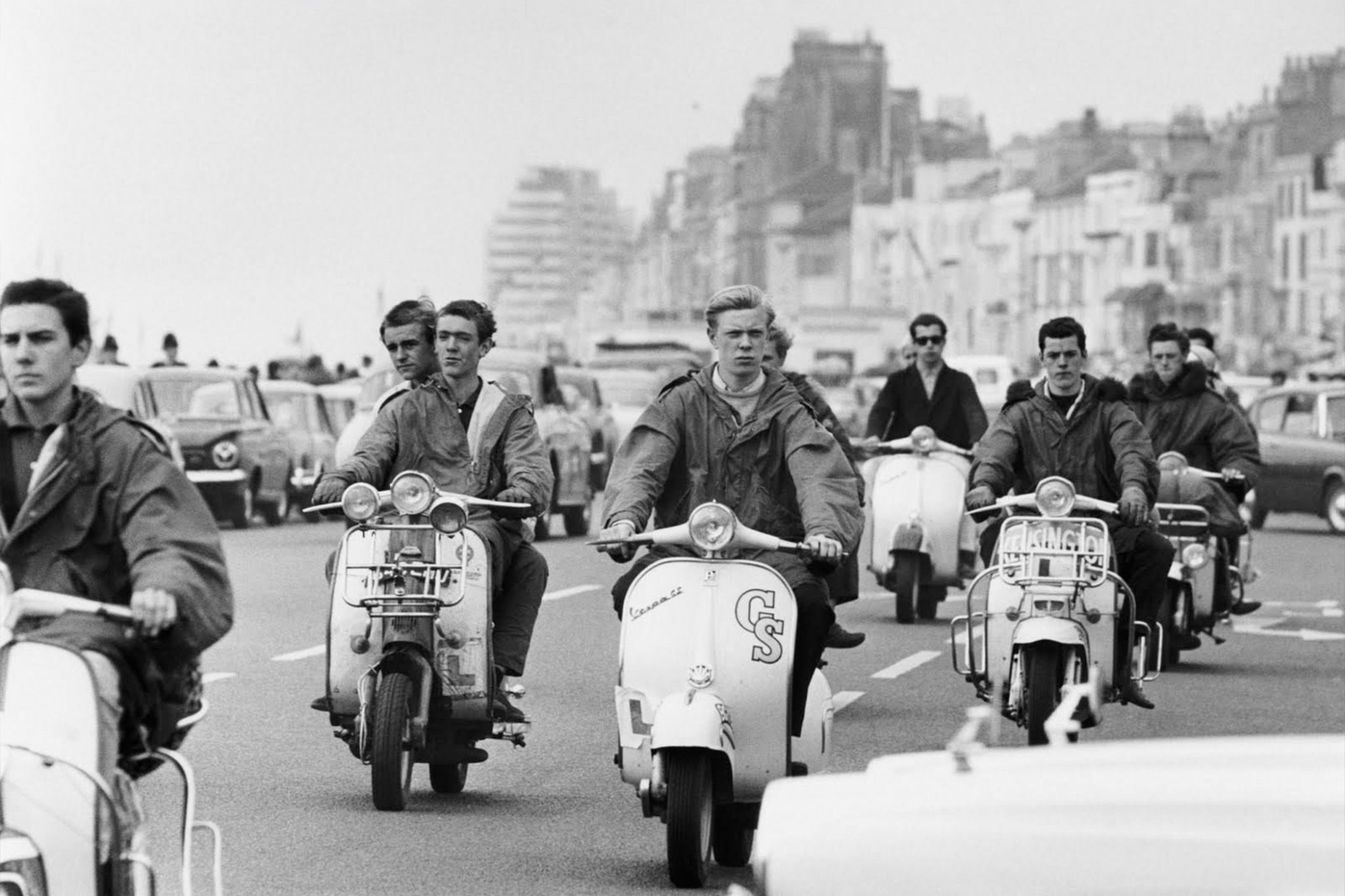

The third option, as attested by Jean-Jacques’ granddaughter, is that the first hallucinogenic 1967 Crash model was an aesthetic response to the changing times in the midst of the ever-growing generation gaps, unprecedented political turmoil, and huge advances in science. Tastes in fashion amongst the young was more rebellious, more avant-garde than ever.

Credit © Terry Fincher/ Stringer/Getty Images

For the watchmakers at Cartier, creating the appropriate technology for the ground-breaking Crash watch was no easy feat. After seeking advice from LeCoultre regarding a fitting movement, the brand turned to its the Wright & Davies workshop to create the gold case. This workshop was, in fact, run by Cartier, yet kept secret by Jean-Jacques in order to avoid thefts. Case complete, the Crash was then sent to Cartier’s watchmaker, Eric Denton.

The Crash from 1967

Credit © Cartier

Denton had to overcome numerous challenges, from creating harmony on such an unbalanced dial to getting the hands to point to the correct time. In total, only around 12 Crash models were created under Jean-Jacques’s first run, for around 1,000 US dollars (about 7,500 US dollars today). Throughout the following decades, they continued to appear in very small numbers – the maximum being a 400-piece limited edition in 1991. By this point, however, other calibres had come into play; the 1990 models, for example, used a round Patek Philippe calibre 5 ½ movement.

Credit © Cartier

While the Crash made a couple of limited but nonetheless extravagant appearances in the early 2010s, from diamond-set to skeletonised designs, it wasn’t until December 2018 that the Crash renaissance began after Kanye West tweeted a picture wearing a classic gold Crash. Ever since then, for the Crash, it seems the only way is up.

In the 1970s, Cartier’s watchmaking became more ubiquitous than ever with the introduction of the Must de Cartier. Significantly more affordable, these pieces opened up the doors to a new generation of Cartier fans, marking a shift from a predominantly elite clientele to the sparky youth of the 70s. Cartier was inspired to create the accessible Must de Cartier line following the resounding success of its famous oval lighter in 1969. Thus, the Must de Cartier opened up a range of new luxury goods to the general public – a pre-emptive response to increasingly global access to luxury goods.

Les Must de Cartier Luxury Goods

Credit © Cartier

For the large part, high-end watch movements in the 1970s were sourced from Vacheron Constantin, while more classic models came from Swiss manufacture Ebel. Despite Cartier London, Cartier Paris, and Cartier New York being united from 1979 onwards under Cartier Monde, this remained the case up until 1988 when Cartier bought up both Piaget and Baume & Mercier. This acquisition enabled Cartier to produce its own movements in its own workshops, marking the dawn of extensive in-house watchmaking at the company.

While Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak burst onto the scene in 1972, and the Nautilus emerged from the horology house of Patek Philippe in 1976, Cartier did not have a large, sporty watch in its portfolio. Enter the maestro, designer Gerald Genta. He is the man behind the original gold Pasha de Cartier from 1985. It’s unsurprising that Cartier took its time with this one. For the most part, Cartier’s watches were significantly smaller, angular or oval – and certainly more classic. Yet the maison and designer were able to create something that still exuded ‘Cartier’, from the Vendôme lugs to the cabochon-set crown – a signature feature that had existed in Cartier watchmaking since 1906.

Other key Cartier features also remained on this vastly different watch, such as the blued steel hands and interplay of square and circular shapes. On the other hand, the Pasha marked a clear departure from classical Cartier watches up until this point. While obviously still far from resembling the steel sports watches being produced by its competitors, the Pasha was significantly more masculine than other pieces in Cartier’s long-standing portfolio, featuring a broad bezel and oversized crown cap – something that would later overturn as many women fell for the model.

Credit © Cartier

At this point, Cartier promptly introduced a number of different sizes, as well as stone-set versions for its female clients. Another important addition to the Pasha was the grid protecting the dial; an incredibly rare sight in the watch world, although already used by Cartier in the first half of the 20th century. Furthermore, the sheer size of the Pasha presented the perfect opportunities to introduce a number of complications, from chronographs and GMTs to moonphase.

Credit © Cartier

In 1990, Cartier even released a complex Pasha de Cartier with a self-winding movement integrating a minute repeater, perpetual calendar, and phases of the moon. The complex creation and exquisitely decorated calibre could be admired via the caseback, proudly bearing the Cartier insignia on the oscillating weight. Finally, by 1990, the elegant maison known for its love of platinum and gold would make the move to steel in the sporty Pasha collection, quietly entering into the sports watch terrain.

Naturally, Cartier today has its own manufacture, producing not only these classic models for which the company is best known, but also highly complicated in-house movements. Furthermore, it is also home to the exquisite Métiers d’Art, home to Cartier’s absolute highest level of watchmaking and traditional techniques.

Credit © Cartier

But returning to our brand portrait: Cartier’s history has contributed to its position today as one of the most reputable of luxury brands; a true beacon of style. Even in this day and age, its visionary watchmakers and designers continue to produce enduringly classic new models such as the Ballon Bleu from 2007. This is perhaps the greatest power of Cartier: its ability to endure. The world has greatly changed since the days of Louis Cartier, yet the company’s ability to not simply move with but actively anticipate the road ahead has enabled it to constantly be on top. Even prior to its horological heyday in the 21st century, its watch designs remain unparalleled in terms of elegance, timelessness, and style.

Credit © Cartier

In this fast-paced century, it is easy to forget how radical some of Cartier’s creations, from the ubiquitous Tank to the worlds’ first modern wristwatch, really were. This is because of the impeccable grace with which their designs were executed. While some luxury brands in the industry today may appeal to the populace by adding a big logo, Cartier sells itself using the magical combination of genius and subtlety. And that’s not all – as its own in-house manufacture and atelier today are testament to, Cartier continues to play host to technical and horological advances that even the most ardent of Cartier’s followers can scarcely fathom.

Brickell, F.C. (2019) The Cartiers. New York: Ballantine Books.

Jordan, S. (2019) How Cartier’s Jeanne Toussaint Inspired and Popularised its Iconic “Panthère”, Sotheby’s . Available at: https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/how-cartiers-jeanne-toussaint-inspired-and-popularised-its-iconic-panthere (Accessed: January 19, 2023).

Sansom, I. (2011) Great dynasties of the world: The Cartiers, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/jul/09/cartier-jewellers-ian-sansom (Accessed: January 19, 2023).

Sotheby’s (2021) The Unusual History of the Cartier Crash, Sotheby’s. Available at: https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-unusual-history-of-the-cartier-crash (Accessed: January 19, 2023).

Storelli, D. (ed.) (2006) The Cartier Collection. Paris: Flammarion.