Discover the Panerai Submersible Luna Rossa Carbotech PAM01563, a limited-edition watch celebrating the partnership with the sailing team Luna Rossa.

One thing is clear: Chopard is the maison for watches and jewellery. A brand that is just as closely associated with the history of the Mille Miglia as it is with the Cannes Film Festival, Swiss precision and a love of products meet cosmopolitanism and charisma. The fact that this status quo seems so familiar, as if it had always been that way, is perhaps one of the greatest achievements of Chopard’s employees and management. There seems to be a fundamental attitude deeply rooted in the company: the history of Chopard and its watches may date back to 1860, but for all its tradition, the company does not allow itself any nostalgia. Rather, the company – at least since the Scheufele family took over in 1963 – has been characterised by a great creative drive and a willingness to change. The manufacture calibres for the Chopard L.U.C collection serve as the best example.

After all, anyone who is even slightly involved in the watch industry knows this: for all manufacturers of mechanical timepieces, manufacturing calibres in-house is an essential building block for success. Because they ensure independence, because they embellish the brand, and because customers now value them.

However, just as Chopard’s jewellery business is still comparatively young with regard to the company’s long history (since 1985), the desire for manufacture movements has only started to grow in the last ten to fifteen years. Looking back, the fact that Karl-Friedrich Scheufele created the Chopard manufacture in Fleurier as early as 1996, and thus the basis for the in-house calibres for the company’s most mechanically sophisticated watches, can be regarded as visionary and highly innovative. After all, he made manufacture movements a Chopard matter long before many competitors, who were often only motivated by the Swatch subsidiary ETA S.A. Manufacture Horlogère Suisse’s announcement in 2013 that it would only supply its own Group brands with movements in future, took up the subject.

Incidentally, a young employee who was still at the beginning of a stellar career assisted Scheufele in the feat of building an own manufacture and creating an own movement: Jean-Frederic Dufour, the current CEO of Rolex.

As a rule, pioneering corporate decisions have both an internal and an external impact. This case is no different. For Chopard and the Scheufeles, the very first L.U.C calibre was both a necessity and a matter of course, a logical next step driven by factors as diverse as production advantages and the demands placed on one’s own work. With the manufacture, many things changed within the company, and this is exactly what was emphasised outside of Chopard.

The movement’s name alone is a commitment to the eternal pact between history and progress: L.U.C, the initials of founder Louis-Ulysse Chopard (1836–1915). In turn, L.U.C 96.01-L (former 1.96) is a reference to 1996, the year the calibre was launched and the year the manufacture was founded. However, the name was reconsidered a few years later, making the matter a little confusing today.

With the first L.U.C 96.01-L movement, Karl-Friedrich Scheufele realised his idea of a calibre that would provide the best possible basis for the elegant creations of his design team. The highest priority was a low overall height in order to be able to produce the thinnest possible watches with harmonious proportions.

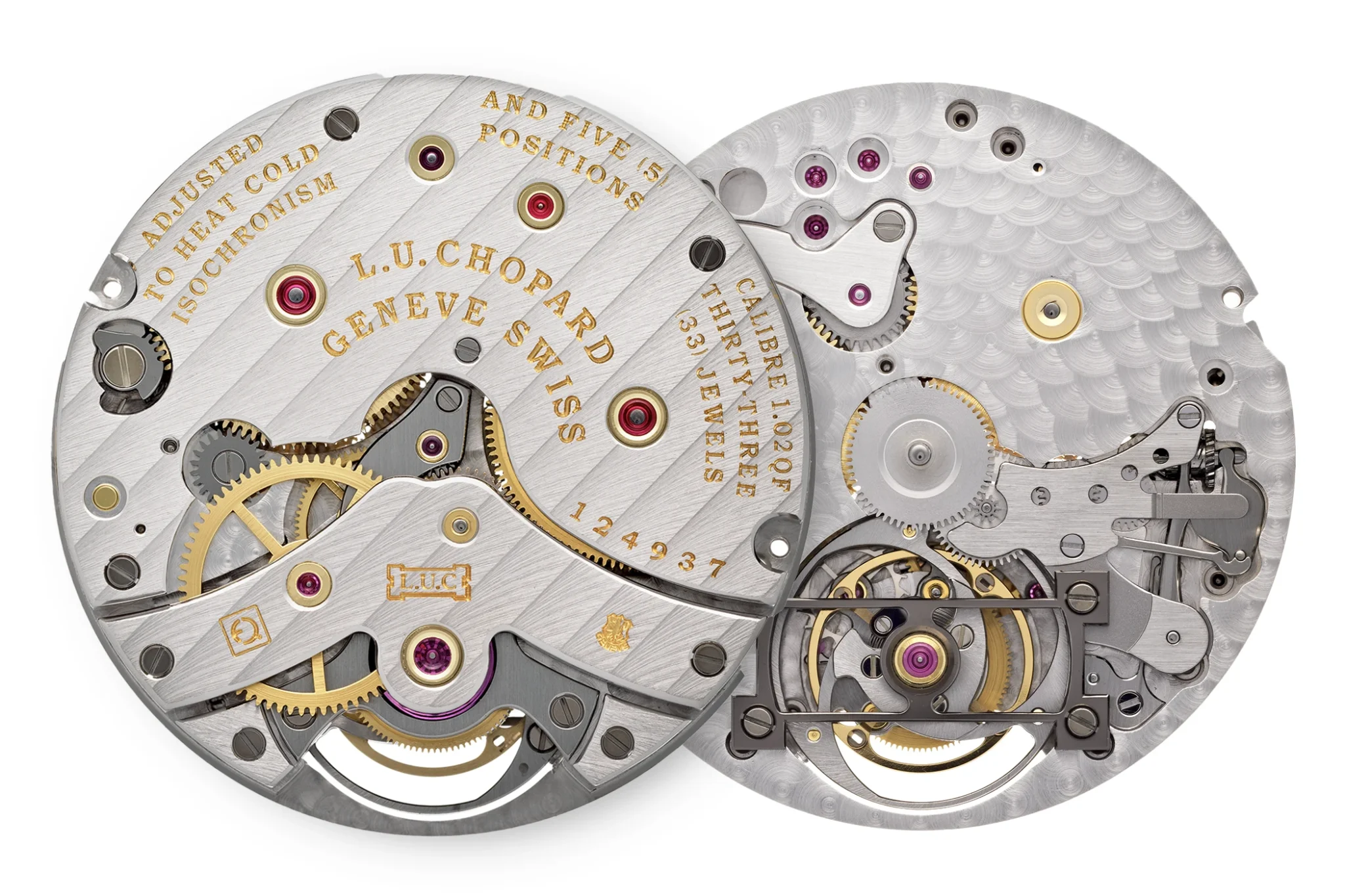

The calibre L.U.C 96.01-L was created in collaboration with Michel Parmigiani. To this day, it is considered a remarkable design, not only because it serves as a base for all subsequent and in some cases significantly more complex movements, but also because it strikes a rather unique balance between maximum reliability and a high standard of appearance and finish.

After all, the Scheufeles did not want just any new calibre to call their own, but one that would also impress external authorities. The calibre’s reliability was certified by the COSC and also met the high aesthetic standards of the Geneva Seal. The L.U.C 96.01-L was one of the first automatic movement with two barrels to have a power reserve of 65 hours. In addition, the movement with its swan-neck regulator has a Breguet spiral with a Phillips terminal curve. Its production is much more complex than that of the more common flat balance spring.

this first calibre was used in different versions of the Chopard L.U.C 1860 with a diameter of 36.5 millimetres: with yellow gold, rose gold, white gold and platinum cases. For gold versions, the watches were fitted with an interchangeable caseback: gold/sapphire and an officer case back. There were no platinum pieces with an officer case back. Watches equipped with the first generation of manufacture calibres are now considered particularly coveted collector’s items.

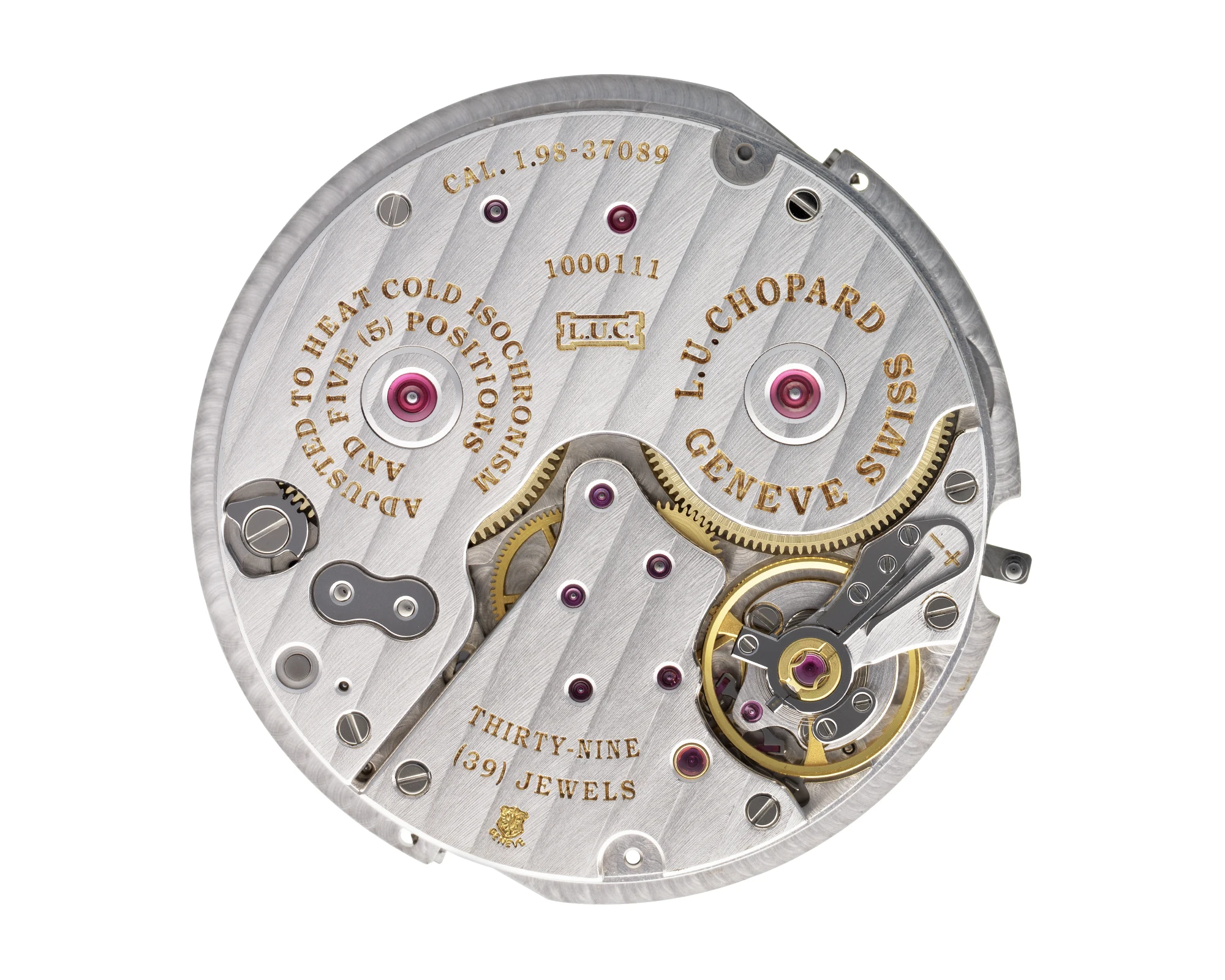

The next member of the then still small Chopard calibre family was presented in 2000: the hand-wound 98.01-L (former 1.98) calibre with four barrels, owing the model its name ‘Quattro’ where technically two ‘twin barrels’ are arranged on top of each other. As they have become typical of the manufacture, Chopard now refers to them as double ‘twin technology’. The barrels enable a power reserve of 216 hours and thus nine days – although the indicator on the dial only shows eight days. The micro-rotor had to make way for these four barrels. The calibre was then installed in the slightly larger L.U.C 16/1863 with a diameter of 38 millimetres. A total of 1,860 pieces were produced in various precious metals.

The guilloché dial is impressive and the combination of the power reserve display at twelve o’clock and the small seconds and date display at six o’clock is incredibly harmonious. Nonetheless, here too, the back view of the movement will likely delight the connoisseur the most: the calibre 98.01-L, oscillating at 28,800 vibrations or 4 Hz, is also COSC-certified and bears the Geneva Seal. The Côtes de Genève stripes on the plate, the hand-finished movement with bevelled edges, satin-finished wheels, the satin-finished bridge – they all are stunning. However, they provide no answer as to why this reference is less in demand on the collectors’ market, at least in comparison to watches with the calibre L.U.C 96.01-L (former 1.96). Thus, it is now traded at comparatively low prices on the secondary market.

The fact that the calibres produced in Fleurier are ennobled with the Geneva seal is incidentally due to a Chopard atelier based in Geneva, which provides the timepieces with the Geneva co-provenance required for the seal.

After more? That’s almost always possible in haute horlogerie and is part of Chopard’s brand DNA. It is therefore hardly surprising that the first two L.U.C models were succeeded by another timepiece that can be regarded as an expression of Chopard’s and its Fleurier-based manufacture’s ambitions. In 2003, the L.U.C Tourbillon was launched. Here, the hand-wound calibre 1.02, also known as the L.U.C 02.01-L due to the aforementioned later renaming of the calibres, does its duty. The movement is based on the calibre 98.01-L (former 1.98) with its four barrels, which has been heavily modified and, as calibre L.U.C 02.01-L, consists of 224 parts. In its cage, the tourbillon alone takes up 62 parts.

With the tourbillon, Chopard entered the grand stage of haute horlogerie with its own movements. The COSC certification for this very movement put the company on an equal footing with Patek Philippe. Understandably, Chopard subsequently further developed the quality of its tourbillons in particular and brought them into focus time and again. A tourbillon with an automatic movement soon became part of the L.U.C family, and in 2011 the Maison presented the ‘3 C’ tourbillon. It received a triple certification from three different institutes: COSC, the Geneva Seal – one would inevitably like to add ‘obviously’ at this point – as well as an additional certificate from the Fondation Qualité Fleurier. The latter is an institution that Chopard had founded with Parmigiani Fleurier, Bovet, and the Fleurier-based Vaucher movement manufacturer in 2001.

Although Chopard is now the only brand still loyal to the foundation, at the time, it was an expression of the Fleurier-based manufacturer’s self-confidence. Moreover, the tourbillon with its calibre 02.13-L was an expression of watchmaking that wanted to prove itself in every way.

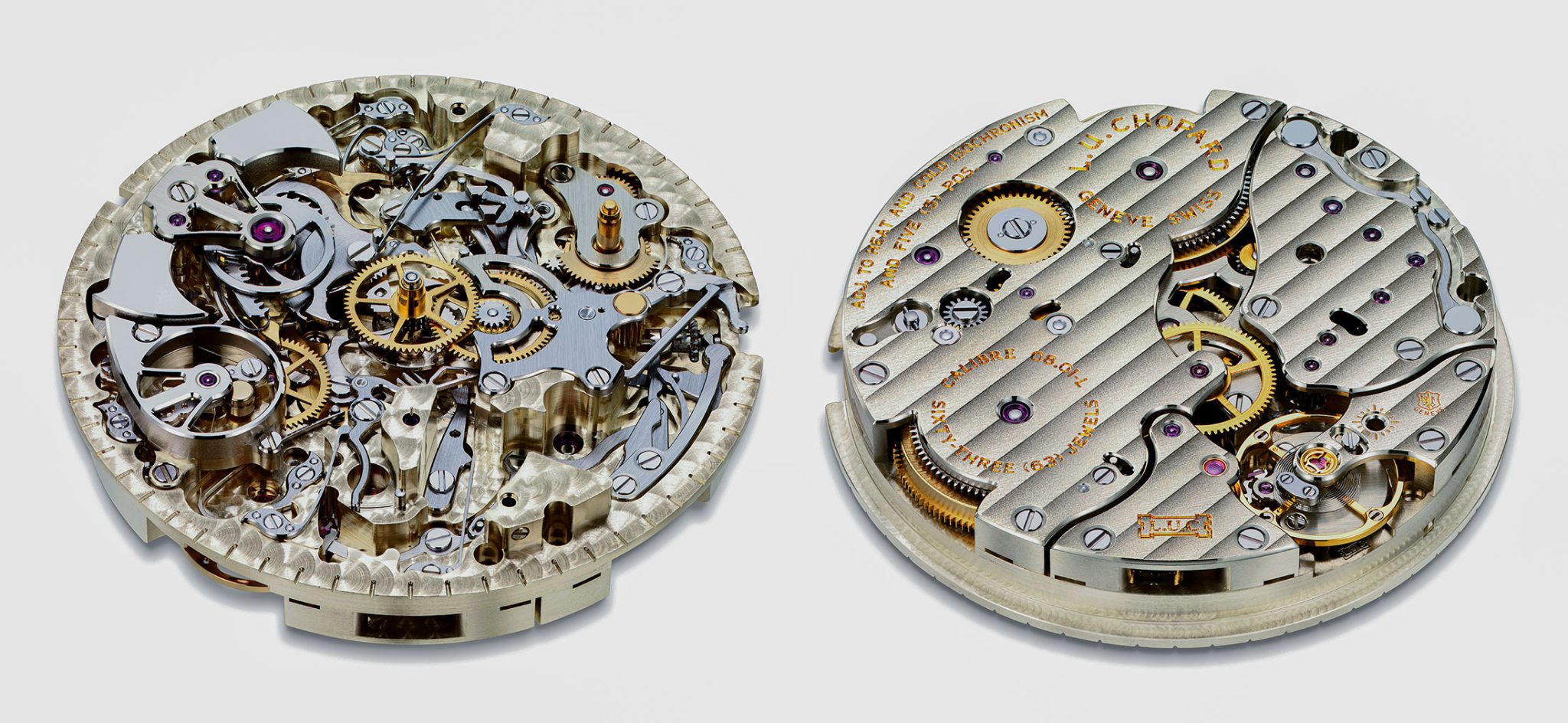

In 2006, a good ten years after the in-house manufacture went into operation, Chopard presented its chronograph calibre L.U.C 03.01-L, the first integrated chronograph with a flyback function of Chopard which operated in the L.U.C Chrono One. Just one year later, the L.U.C calibre 11CF, nowadays known as the L.U.C 03.03-L, replaced it. With its 60-hour power reserve, it appears in the chronograph Superfast models as well as the Mille Miglia special editions in slightly different variations.

L.U.C 03.03-L

Apart from the fact that a manufacture chronograph movement is still regarded as the highest form of watchmaking, it was understandably a matter of entrepreneurial concern for automobile and racing enthusiast Karl-Friedrich Scheufele to be able to also offer an in-house manufactured movement in this field. The chronograph movement with vertical clutch was subsequently expanded even further and the perpetual calendar function was added to the L.U.C 03.10-L version.

The mid-2000s were a time of great creativity at the Chopard manufacture. It is probably fair to say that a successful beginning had been made and it was now time to shine across all fields. In addition to a L.U.C perpetual calendar (2005), the watchmakers also ventured into a comparatively ultra-rare complication. In 2006, they presented the L.U.C Strike One with the 96.14-L calibre.

Timepieces with striking movements are generally regarded as the pinnacle of watchmaking. Patek Philippe is considered the grand master in this field, but Chopard is now also highly respected – not least because of models such as the Strike One.

Its movement was also based on the first calibre L.U.C 96.01-L (former 1.96), which was supplemented by an hour striking mechanism whose hammer was visible through the dial. Upon activating the mechanism, the hammer’s movement emits an acoustic signal on the hour, also known as ‘Sonnerie au Passage’.

While the very first L.U.C Strike One could be optimised from a purely aesthetic point of view – at least from today’s perspective – it holds an immeasurable significance as the manufacture’s first striking watch.

The calibre 96.14-L was followed by the L.U.C Full Strike minute repeater with the calibre L.U.C 08.01-L. It was presented in 2016 and was awarded the ‘Auguille d’Or’ at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie in 2017. Above all, it is characterised by the fact that the gong is not made of metal, but of a sapphire crystal monobloc. Not only does this construction create an extremely clear sound, but also a constant one.

Subsequently, the maison expanded the technology from the ‘Full Strike’. For example, its successor was a combination of a minute repeater and a tourbillon. Moreover, it was used in the L.U.C Strike One. The model presented itself as a 25-piece limited edition with the successor calibre L.U.C 96.32-L to mark the 25th anniversary of the L.U.C collection in 2021.

In the world of Chopard, the L.U.C models and calibres represent the height of the collection. They are the benchmark by which the company measures itself time and again. Even today, 28 years after it opened its doors, the manufacture only produces a few thousand L.U.C calibres each year. From the classic three-hand watch to the manufacture chronograph and the minute repeater with striking mechanism, the workshops in Fleurier and Geneva have mastered everything that is good and rare.

For Chopard, these calibres have a radiance that is in no way inferior to that of the brand’s most exclusive jewellery necklaces. They demonstrate how seriously Karl-Friedrich Scheufele and his family take their craft, no matter how charmingly playful the models in the ‘Happy Diamonds’ series may seem.

For the family, L.U.C is a combination of tradition and innovation, and an essential building block for the future. Because no matter how glamorous Chopard may seem nowadays, it is ultimately this collection, with its sophisticated calibres, that collectors around the world laud above all others when they think of Chopard.