Blancpain and Swatch have presented a watch together with the Bioceramic Scuba Fifty Fathoms. But how cool is the collaboration in reality?

A vast structure of concrete and glass forms Cartier’s manufacture in the UNESCO World Heritage Site watchmaking town of La Chaux-le-Fonds. Across the panes of glass, which reveal only the subtlest glimpse into the world of watchmaking on the other side, the unmistakable cursive Cartier logo spreads itself across the austere building’s exterior, alongside the printed words: Manufacture de Haute Horlogerie. It’s an imposing sight. Passers-by driving through the town’s highway peer out of their windows, often stopping to take a picture from the asphalt car park across the busy Allée des Défricheurs, which leads the way to Le Locle before curving across the adjacent French-Swiss border. On dark winter evenings, the snow-dusted structure glows with warmth from within, while on balmy summer mornings, bright light floods through this horological edifice. Inside, Cartier’s watchmakers diligently produce some of the world’s most iconic watch models of all time: the Tank, Santos, Pasha and many other design icons start life right here.

The Cartier manufacture, perched on the outskirts of Le Locle

Credit © Cartier

Amidst the sight of this mighty manufacture, you might be forgiven for missing the quaint Swiss farmhouse nestled to its left. During the warmer months, rosy red apples and plump purple plums grow up the sides of the stone walls. An immaculately kept front lawn and ornamental box hedges surround the property, well-watered and lush green. During its 17th century heyday, this rural farmstead, which sits at an altitude of around 1,000 metres, was revered as the most illustrious in the region. On Valentine’s Day of 1859, however, a fire completely destroyed the farmhouse, leading to its reconstruction from the ground up (albeit in a more modest form) in 1872. Today, this charmingly traditional farmhouse, with its old wooden shutters and carefully curated flower borders, is home to Cartier’s horological treasure trove: the Métiers d’Art.

Nestling amongst the trees: the Cartier Métiers d’Art

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

Technically speaking, several watch manufactures engage – both internally or with external suppliers – in the creation of Métiers d’Art watches; Vacheron Constantin, followed by Chopard, Hermès, Blancpain, Piaget, and of course Cartier are the first to spring to mind. But for the non-French speakers amongst us, what exactly does it involve? Translating as ‘Masters of Art’, Métiers d’Art watches use age-old traditional techniques, either preserving or integrating them into the world of horology. Such watches require many hours of painstakingly difficult, carefully executed labour. Generally pieces destined for the watch world’s absolute top collectors, the timepieces are inevitably of high value, both monetarily and as significant pieces within the brand’s portfolio. Métiers d’Art ateliers also hold great cultural worth due to their upholding and preservation of what would otherwise surely be long-extinct artisanal techniques, were it not for Switzerland’s luxury horology houses and their dedicated craftsmen.

The dedicated craftsmen dwelling inside the Métiers d’Art

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

When public figures are briefed for television or radio interviews, media trainers will often tell them to stick to three key messages, thus ensuring that their arguments remain concise, comprehensive and focused. Much in the same way, the Cartier Métiers d’Art maintains its meticulously curated portfolio and impeccable production process by defining itself as having only three missions. The first is to preserve: Cartier educates its craftsmen here on many techniques you will not encounter at watchmaking school. The second is to share: the craftsmen here sometimes work on one product together, from watchmaker and jeweller to gem setter and enameller. The third and final mission is to innovate: from the first pilot’s wristwatch to the deployant buckle, innovation runs in Cartier’s blood and it’s not something the company plans to let go any time soon, least of all at its artisanal Métiers d’Art.

Cartier’s main manufacture was built in 2000, with the company’s ‘Think Tank’ squatting behind the building following in 2007. Following the decision to establish a Métiers d’Art department in 2008, the neighbouring farmhouse and its surrounding land was eventually purchased in 2010. Upon making the acquisition, Cartier pledged to keep the farmhouse much the same despite planning extensive renovations. Thus, the architects even kept the layout and orientation of the farm exactly the same as the original farmhouse; partly an environmentally-friendly decision to ensure that the Métiers d’Art’s 21st-century inhabitants remained warm throughout the biting Swiss winter.

Dusk falls over the converted farmhouse housing the Métiers d’Art

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

By 2014, the renovated building was ready for use. Initially destined to house ‘exceptional craftsmanship’ upon its official inauguration that same year, the luxury watchmaking division was integrated into the Métiers d’Art in 2017. Today, specialists from more than 20 different professions strive to create Cartier’s most exceptional pieces of the modern age.

The moment you step across the threshold and onto the ‘Cartier’ branded doormat, you enter a world of luxury, history, and craftsmanship. While the 350-square metre ground floor was once shared by farmers and cattle alike, today it holds another significance entirely. Cartier’s architects and interior designers took inspiration from the first rural watchmaking workshops of the Jura, to which locals would flock in the harsh winter months to make extra money producing extra cog wheels and various other components. With its interior design executed to perfection, the space combines the old and new, with traditional wooden furnishings and stone floors meeting vast sheets of glass that draw in natural light.

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

Another idea behind the interior design was to bring the surroundings into the building; the limestone comes from Neuchâtel, while the wood used for its traditional fixtures are taken from the farm’s original outhouses. For other elements, Cartier’s architects went in search of old wooden panels for walls and ceilings from the local area or across the border, seeking out natural stone walls and historic fireplaces. Where the old could not be found, they relied on starkly modern materials, from the steel open staircase to the glass elevator. It’s a place full of quirks; take the neo-Gothic chandelier in the airy room opening out to the garden, for example, which was once the property of Yves Saint Laurent, before eventually being purchased by former Cartier CEO Bernard Fornas at the auction of the Pierre Bergé collection.

The neo-Gothic chandelier once belonging to Yves Saint Laurent

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

The Cartier Métiers d’Art is carefully organised floor by floor, section by section, with each employee, from product development manager to marquetry expert, playing a highly specific and indispensable role. Openness is intentionally at the heart of the building’s architecture, allowing the various professions to come together, conceiving and creating as one. Let us ascend to the first floor of the Cartier Métiers d’Art.

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

On the first floor, Cartier’s expert gem-setters work on some of the Métiers d’Art’s most innovative and unique pieces. One stand-out watch that has garnered much attention since its inception is the astonishing Ballon Bleu with patented vibrating diamonds. Every diamond is set onto a micro-spring, with the springs designed to all vibrate at the same frequency. This patented innovation by Cartier also integrates a shock absorber to ensure that even if the watch is subject to shock, the diamonds can continue to move perfectly in sync.

The Cartier Ballon Bleu with patented vibrating diamonds

Credit © Cartier

On the first floor of the Métiers d’Art, gems glitter left right and centre, as artisans set a colourful Crash Tigrée Métamorphoses with sparkling stones or adorn a jaguar’s head, destined for a visible hour Panthère Entrelacé watch, with glowing emerald eyes.

For jewellery watches, many of which play on Cartier’s hallmark panther, the silhouettes are firstly sketched out by hand, then after producing a paper prototype, a wax sculpture is created. This is then turned into precious metal either using traditional moulding or by computer – the latter involves 3D printing with a special wax. Once the shape has been moulded, the gem-setting is done by hand. To ensure the right size and shape of gems are used, the artisans are aided by colour-coded digital drawings. After marking the spaces where the gems can go, the holes for the gems are set with special tools. Glue is strictly forbidden in the process. The most challenging of the gem-setting done at the Métiers d’Art is the so-called ‘invisible gem-setting’. Alongside requiring the utmost precision, the artisan must carve grooves into the diamonds in order to create a floating effect. Some of the stones Cartier’s specialists work with on a day-to-day basis measure a mere 0.6 mm in diameter.

Credit © Swisswatches

Cartier’s Coussin (cushion) watch models, which use a gold mesh and were developed by Cartier’s Research and Innovation team alongside their close suppliers, also require an expert in the field who can fortunately be found in the Métiers d’Art. Firstly, the mesh for the outer case is 3D printed, before the structure inside it is removed by a jeweller – this process alone takes a week – who then ensures the case is smooth before inserting a polymer to create the flexible bouncing effect of the mesh case. Finally, hundreds – or even over a thousand on some limited editions – of diamonds must be set into it, further increasing the many hours of work required to create one single timepiece.

The Métiers d’Art also now serves as the manufacturer of Cartier’s mystery watches, such as the recently conceived and much-lauded Masse Mystérieuse. Alongside several aethereal mystery models, the first floor also works on the creation of other exquisite skeletonised models, from Santos to Pashas with exposed movements designed in-house and finished to perfection.

When one thinks of enamel watch dials, the first thing to come to mind is the traditional art of a beautifully painted dial, perhaps featuring an idyllic scene (think Patek’s recent Rare Handcrafts exhibition in Japan) using powdered glass and a kiln. Today, such specialist enamel dials at Cartier are created by a young female former student of art. Sitting high in the wooden loft of the Métiers d’Art, we observe silently as she carefully paints the light blue into a Crash Tigrée Métamorphoses. The atmosphere in the loft is serene, aside from the scraping and whirring of various tools. She is not alone, but rather joined by a range of specialists who also master other related traditional techniques, from cloisonné, champlevé, plique-à-jour and grisaille enamel, to more recently revived skills unique to the maison, such as gold paste enamelling, filigree enamelling or enamel granulation. Each one is a stunning artistic form and unlike anything seen in the industry.

The Cartier Crash Tigrée Métamorphoses

Credit © Swisswatches

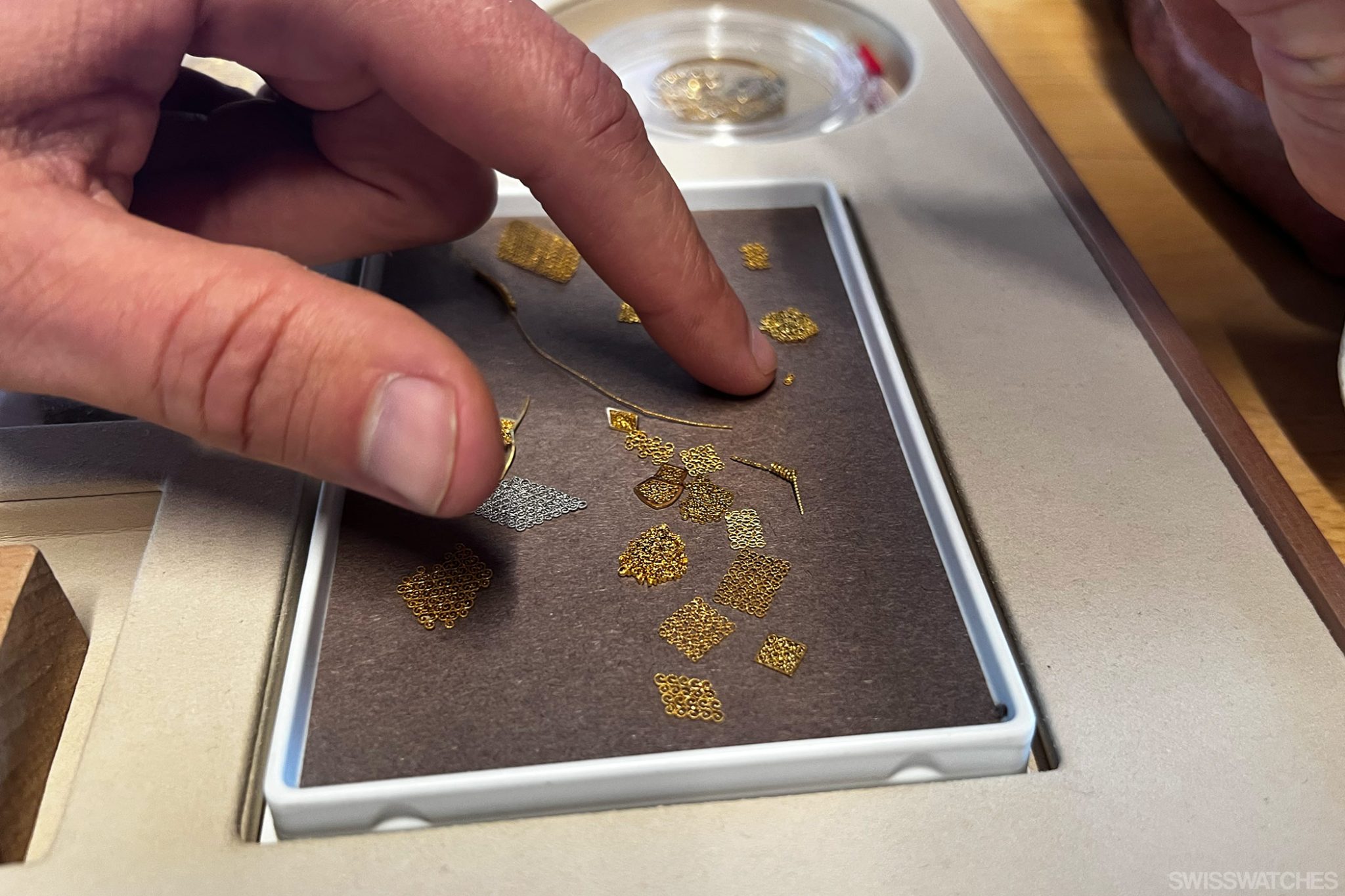

First appearing almost in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) roughly 3,000 years ago, the ancient art of filigree involves artisans carefully fashioning fine gold or silver wires to create patterns comprising tiny curled rings, which are delicately soldered together to create a motif. At the Métiers d’Art, Cartier build upon this by adding in other coveted materials such as platinum and even diamonds. Done entirely by hand, of course, working with Cartier’s specially produced micro-wires requires the utmost dexterity and artistic skill. Creating one dial alone can easily occupy an employee’s time for a month.

Credit © Swisswatches

Gold filigree, gold bead granulation, and engraving are also important practices in Cartier’s repertoire of expertise. The Etruscan granulation technique was conceived by the Italian Etruscan people back in Ancient Italy (roughly between the 8th and 3rd century BC), when they would adorn death masks for their kings with finely decorated crowns. The technique consists of joining tiny spheres or granules to a backplate in intricate patterns.

Gold bead granulation presents particularly many hurdles, not least because the artisan works with both gold balls, crafted from a long gold rod, and a gold baseplate. As both gold components naturally have the same melting point, the question is: how did Etruscans work with both at the same time? To find out the secret behind the technique, Cartier worked alongside the Louvre Museum in Paris, discovering that the Etruscans used a special disappearing substance to change the melting point and keep all gold components intact. Most famously, Cartier Métiers d’Art created the Rotonde de Cartier in 2008, which actually served as the catalyst in the creation of the Métiers d’Art.

Credit © Swisswatches

Having mastered Etruscan granulation by sharing wisdom with art historians, craftsmen, and specialists alike, Cartier then added its own twist by creating ‘enamel granulation’, replacing the gold beads with enamel beads. This differs from other enamelling techniques due to the fact that the enamel beads are created using a blowtorch, rather than a kiln. The most stunning and recognisable example of the technique is the mesmerising limited edition Ballon Bleu de Cartier enamel granulation watch that appeared at SIHH in 2016, proving the power of the then-recently inaugurated Métiers d’Art.

The Ballon Bleu de Cartier enamel granulation watch from 2016

Credit © Cartier

The Métiers d’Art can also take credit for Cartier’s stunning animal-themed grisaille watches. We pause to admire a ‘blonde Limoges’ dial featuring a sultry tiger. The title ‘blonde Limoges’ refers to the French city of Limoge, best known for its historic production of decorated porcelain. Cartier’s grisaille watches use the same calcium powder that is mixed with porcelain to create the whitest of white for its special dials. Applied to a jet-black dial, the ‘blonde Limoges’ layers are added one by one. Between each layer, the dial is placed into the kiln. One or two layers and accompanying firings will create a grey shade, while no less than eight intense stints in the kiln are required to create the very white colour achieved by the end. The entire process requires much dexterity and patience on the side of the artisan.

Credit © Swisswatches

For other watch dials, Cartier’s Métiers d’Art take the process a step further by replacing ‘blonde Limoges’ with something even more precious: gold. Yet the obstacle, as was the case with Etruscan granulation, was the melting point. How might one put an intricately designed dial in an oven without the painted gold melting into it? Ever the masters of innovation, Cartier of course sought the answer by seeking people who might be able to impart their own artistic wisdom.

Credit © Swisswatches

While the maison often works with scientists and engineers, they found their solution not through a scientific laboratory, but rather the opposite: they found it in religion. Cartier journeyed to meet with French Benedictine monks residing at Ligugé Abbey, a monastery with roots dating back to the 4th century, who held the key to understanding the gold grisaille technique. In return for preserving the monks’ savoir faire, the monks shared their artisanal secrets (which, to this day, the honourable house of Cartier will not disclose).

Ligugé Abbey

Credit © Collegio Sant’Anselmo

The ancient art of marquetry dates back as far as the farm itself, to the 17th century, when the technique was used in art and even furniture. Also popular in Paris in the 19th century, it became a fashion amongst wealthy French families to luxuriously cover entire walls with marquetry creations. Marquetry eventually arrived in the horological world, surprisingly late, in the 20th century, predominantly appearing on table clocks. Traditionally using the affordable material straw (but also involving other materials such as mother-of-pearl or stone), the process comprises opening up the straw with a blade before flattening it with a burnishing bone tool. Following this, the artisan can draw his desired pattern onto the straw, before cleaning and assembling it.

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

Marquetry at Cartier’s Métiers d’Art has been on the scene for just over a decade. In 2012, the horology house commissioned a freelance specialist to create a Rotonde de Cartier model featuring a koala, housed in a 35 mm case with a diamond bezel. Since then, marquetry creations at Cartier have varied greatly, from table clocks to the colourful Clé de Cartier jaguar watch with a glinting emerald eye. Today, ever-experimental Cartier uses several varying natural materials; straw, wood, and even flower marquetry. We admire a beautiful flower marquetry dial currently under construction, using roses from Ecuador. The art of flower marquetry is exclusive to Cartier, having been introduced a couple of years ago.

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

The dials are full of artisanal interplay, with some even using marquetry, enamelling and miniature painting on one single dial. When we visit the loft, Cartier’s marquetry specialist is currently absorbed in the ‘Marquetry de Vries’ technique, christened after the artist of the same name. This skill involves taking several pieces of straw and placing a 24-carat gold leaf in the middle. The wooden parts are then scraped away to reveal various shades of wood alongside flashing glints of gold. Various types of wood are used at Cartier, from the pinkish tones of tulip tree to a rare, dusky Macassar ebony, creating a polyphony of colours and tones.

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

Creating marquetry dials takes around 50 hours, during which time the artisan will work with around 200 pieces of straw. Cartier’s supplier provides the maison with around 60 different colours. While some woods are explicitly colourful because they are dyed, others are darkened using heat alone. To colour the wood naturally, the straw is carefully placed in hot sand, which adjusts the colour of the material over specific time periods. At the end of the marquetry process, lacquer is added to counter the obstacle of aging straw, meaning the natural materials are resistant to UV rays.

View of the upper levels of the Métiers d’Art

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn

Here in this serene little loft, with the light streaming in through the wooden beams and panes of glass that gaze out onto the melancholy Swiss countryside with its low-hanging clouds, I realise that marquetry makes for the perfect place to end our tour of the treasure trove that is Cartier’s Métiers d’Art. Four hundred years ago, the straw being used to create resplendent pieces of horological art was fed to cattle, stamping their hooves on these same stone floors. The chronicle of this little Swiss farmhouse has been transformed; its destiny today is to breathe new life into ancient preserved crafts from across the millennia. All the while, Cartier steadfastly treads into the future.

Credit © Benjamin Anthony Monn