Bulgari is presenting a new world record at Watches & Wonders 2025 with the Octo Finissimo Ultra Tourbillon – the thinnest tourbillon.

Rolex’s new Land-Dweller watch model’s movement presents a novel escapement that is well worth a closer look. What are its key features – and which inherent limitations of the Swiss lever escapement does it aim to overcome?

The escapement in a mechanical watch is essential: without it, the mainspring would cause the gear train and hands to unwind at breakneck speed – and after just a few seconds, everything would come to a halt. Together with the balance wheel, the escapement regulates the gear train, ensuring accurate timekeeping.

Today, the Swiss lever escapement is used in 99 percent of all mechanical watches. In 2015, Rolex introduced the Chronergy escapement, which increased the efficiency of the Swiss lever design by 15 percent thanks to lightweight construction and optimised geometry. Now, Rolex has presented a new escapement that goes much further. It operates without a traditional lever, instead using two escape wheels, and is reminiscent of Breguet’s natural escapement.

To understand the strengths and weaknesses of the various escapement types, we need to take a closer look.

In 1757, Thomas Mudge invented the lever escapement. Subsequently refined over the years, it is today ubiquitous in the form of the Swiss lever escapement. Let us briefly recall how it works: one of the lever’s two ruby pallets halts a tooth of the escape wheel with its outer face. As the balance swings back, it moves the lever, which releases the tooth. This then slides over the impulse face of the opposite pallet, transferring energy to the lever, which in turn delivers it to the balance. The second pallet functions in the same way – with the difference that, due to the geometry of the lever, it delivers the impulse in the opposite direction of the swing.

Credit © Wikipedia

The Swiss lever escapement offers many advantages: it is robust, allows the balance to restart from a standstill, can be finely adjusted, and is suited to industrial production. It is also precise, as it involves relatively little friction – provided it is well lubricated. And this brings us to its main weakness: if it is insufficiently lubricated or the oil dries out, the movement stops. The sliding friction, even with the optimised combination of ruby and steel, results in too much energy loss. Alongside magnetic interference, this remains one of the most common reasons why a watch needs servicing. This issue already occupied the mind of Abraham-Louis Breguet. At the time, lubricants were far less effective than they are today.

In 1789, Breguet developed the échappement naturel – the natural escapement. In essence, he modified the chronometer escapement he had created a decade earlier, which functioned without lubrication. That earlier system delivered an impulse to the balance in only one direction, making it suitable for marine chronometers but not for pocket watches, as the balance would not restart on its own if stopped by a shock.

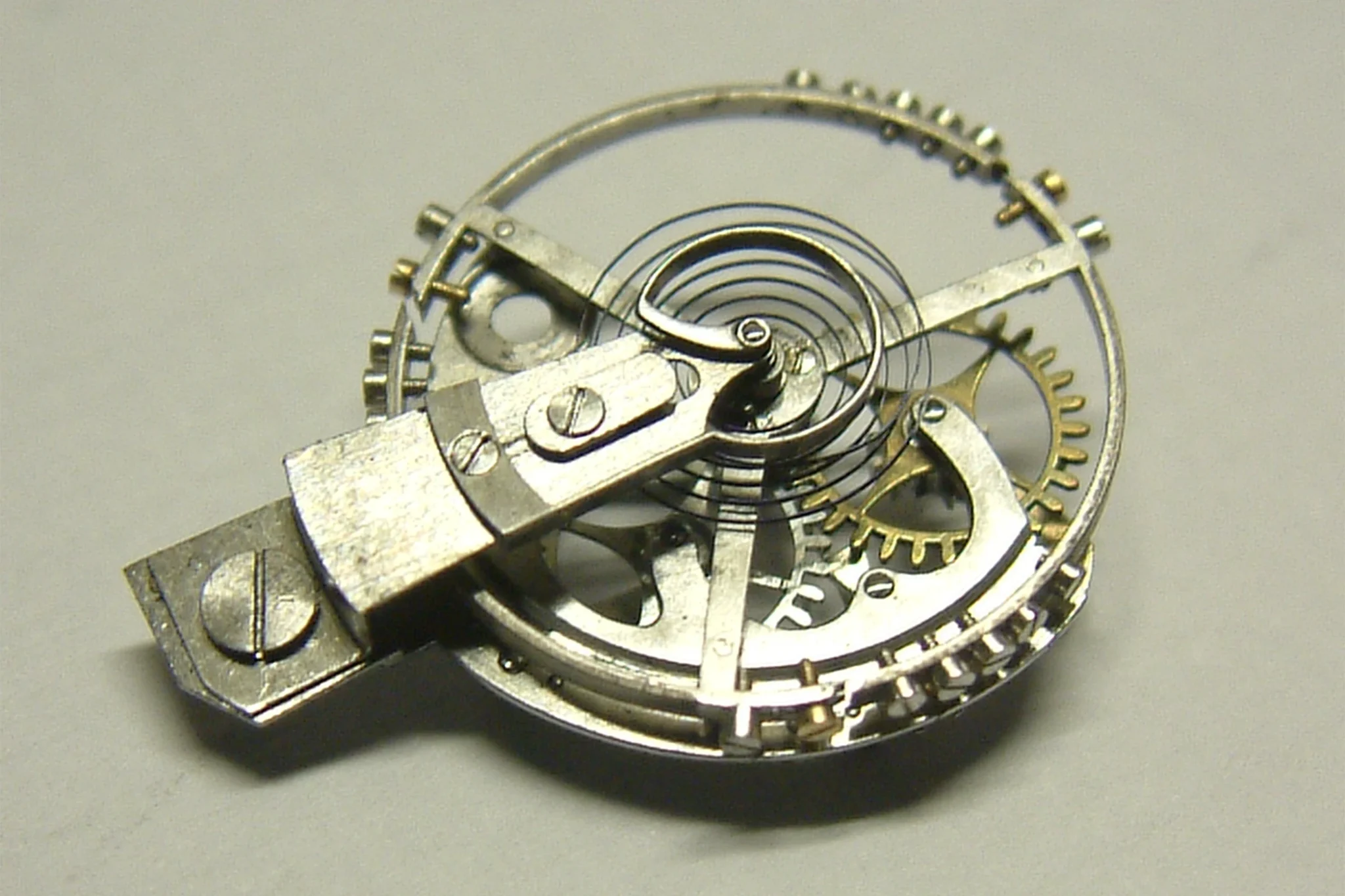

Breguet’s complex natural escapement differed from the lever escapement in several key respects: instead of a single escape wheel, it used two interconnected escape wheels, and a detent-style lever in place of a traditional anchor. The fundamental difference: while the detent lever – like the anchor before it – was moved by the balance and locked the escape wheels, the impulse was no longer transmitted via the anchor, but directly from the escape wheels to the balance, which had two ruby impulse pallets for this purpose. Unlike the chronometer escapement, this meant the impulse was delivered in both directions. As a result, the escapement was self-starting and operated without lubrication.

Credit © Kjorford / Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 3.0

However, Breguet only fitted around 20 pocket watches with this system and otherwise continued to use the lever escapement. One reason was the complexity of the natural escapement – only his most skilled watchmakers were capable of assembling and adjusting it. In addition, the second escape wheel introduced more friction, and the backlash and play between teeth created a degree of instability.

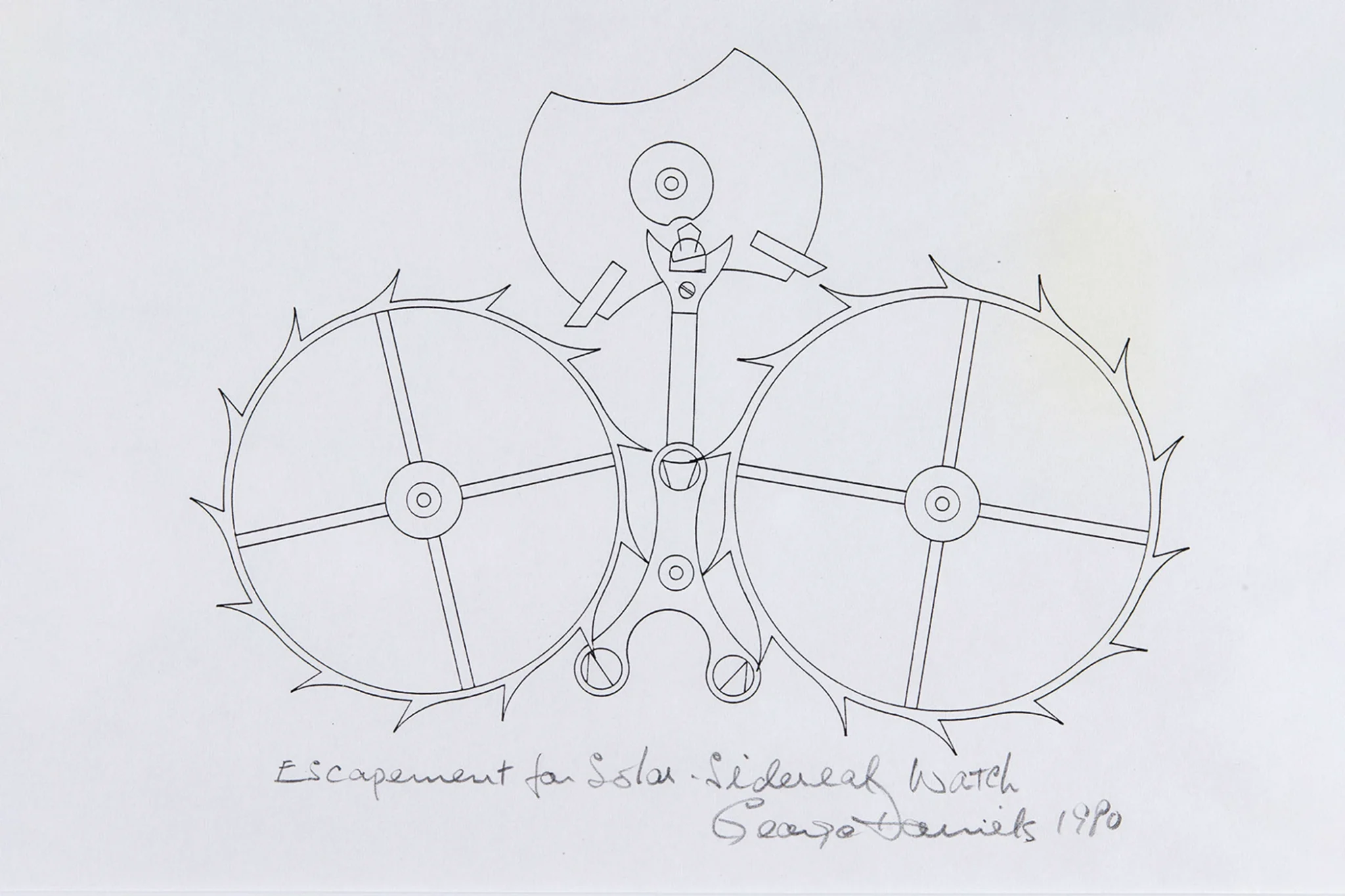

Beginning in the 1980s, several systems based on Breguet’s natural escapement were developed, largely thanks to the pioneering work of George Daniels, who had long been researching lubrication-free escapements. In 1982, Daniels built a version of the natural escapement into his pocket watch Space Traveller I, using two separate gear trains and individual mainspring barrels to power the two escape wheels independently – a design that addressed the issues of friction and backlash. In 1997, Derek Pratt experimented with spiral springs on the escape wheels.

Credit © Sotheby’s

Later, new manufacturing techniques and materials made it possible to overcome some of the earlier limitations. Kari Voutilainen, François-Paul Journe and Laurent Ferrier all created watches using versions of the natural escapement.

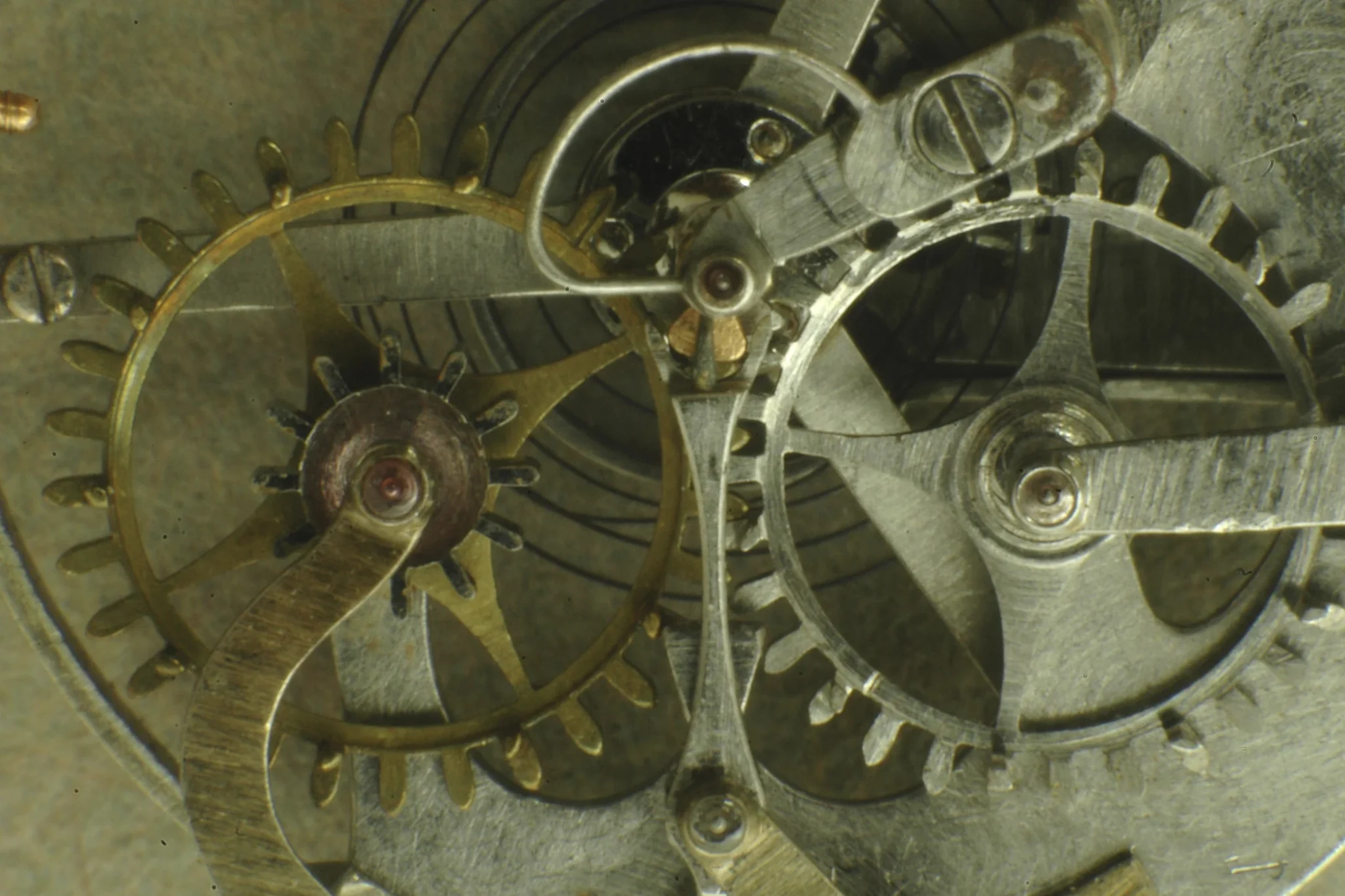

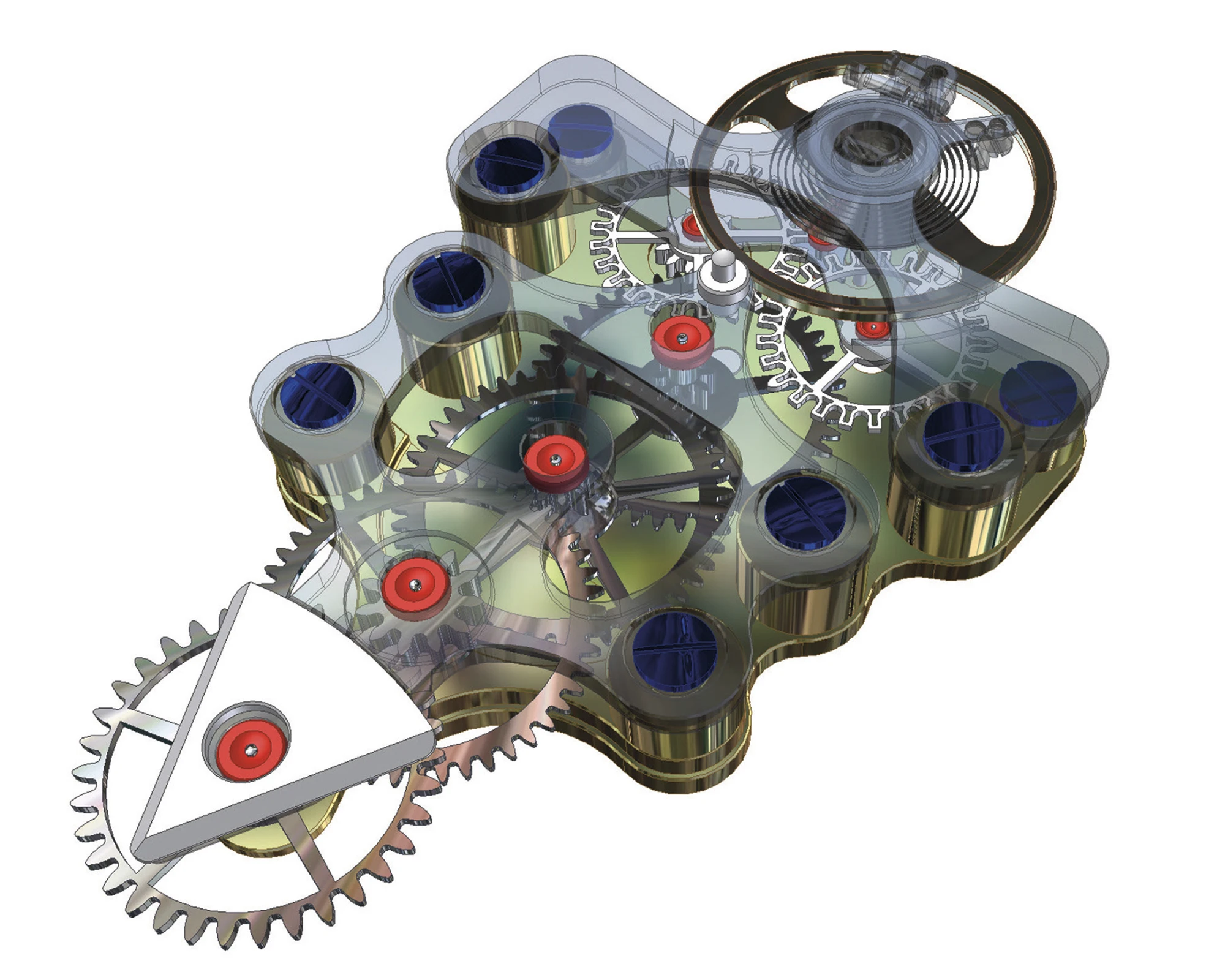

Ulysse Nardin took things one step further in 2001 with the revolutionary Freak, developed by Ludwig Oechslin. In the Dual Direct escapement, the two escape wheels were not connected by gears on a shared axis, but instead meshed directly with each other. Five extended teeth on each wheel delivered impulses directly to the balance. In addition, the wheels were made from silicon – extremely lightweight, low-friction, and manufactured to exceptionally tight tolerances.

Credit © Phillips

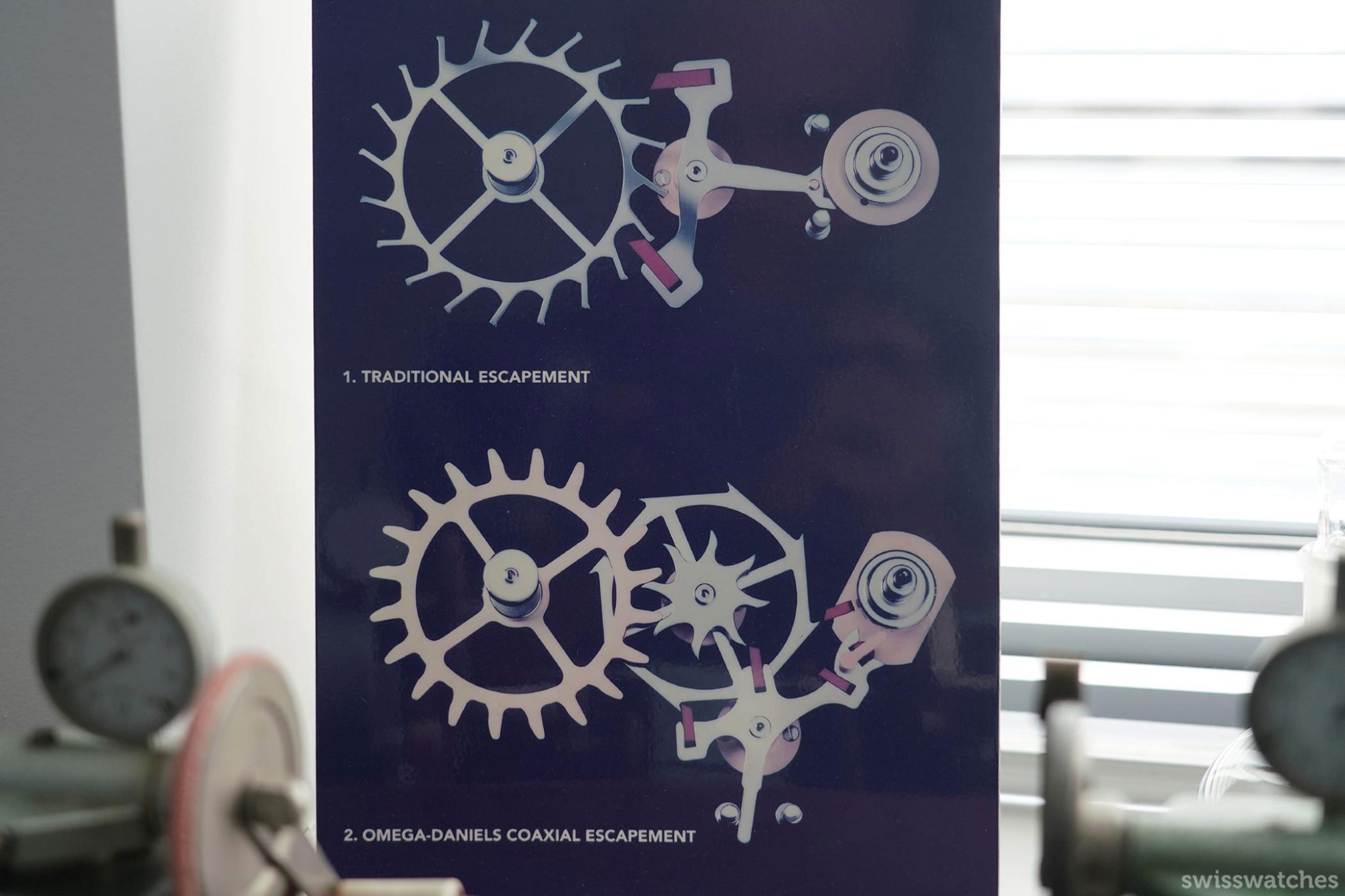

And what about Omega’s Co-Axial escapement? Is it a natural escapement or a lever escapement? The mechanism developed by George Daniels is essentially a hybrid: it uses only a single escape wheel, and the balance receives an impulse in both directions (meaning it is self-starting). However, only one of those impulses comes directly from the escape wheel; the other is transmitted indirectly via the lever. The geometry of the system eliminates the need for an inclined plane during energy transmission. In theory, the escapement should function without lubrication – but Omega has found that oiling the pallets still improves performance.

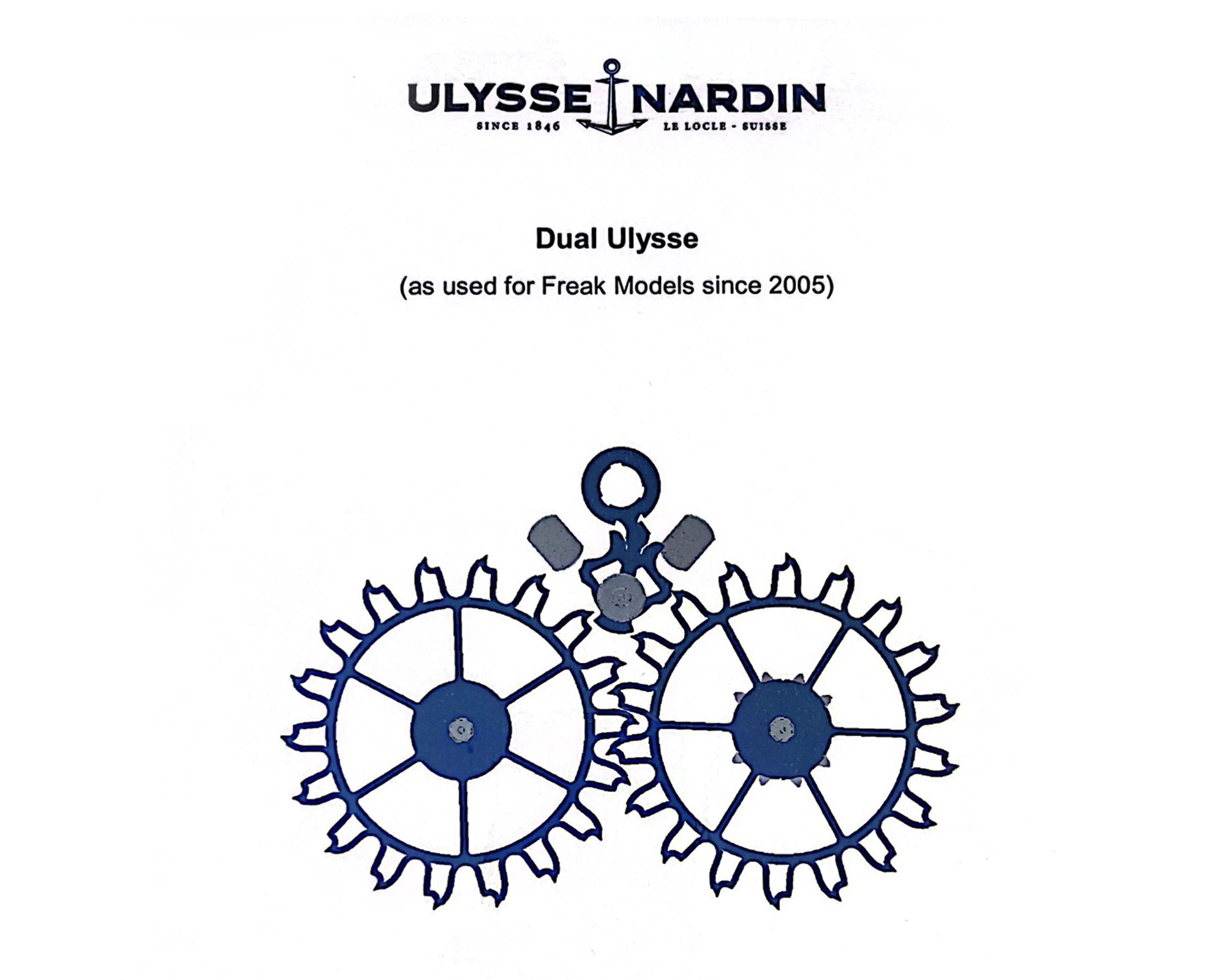

In 2005, Ulysse Nardin introduced the Dual Ulysse escapement in the second generation of the Freak. This system, also developed by Ludwig Oechslin, retained the two interlocking escape wheels, but they no longer delivered the impulse directly to the balance. Instead, energy was transmitted indirectly via a lever – much like in the traditional lever escapement.

Credit © Ulysse Nardin

The symmetrical mechanism operates as follows: first, a recess in a tooth on the left escape wheel locks into the upper arm of the lever, halting its motion. When the balance moves the upper part of the lever to the right, the right-hand wheel is released, and a tooth from the left wheel engages the lower part of the lever, which then delivers the impulse to the balance. The same process then occurs on the opposite side.

The Freak 28’800 from 2005

Credit © Ulysse Nardin

The escapement remains lubrication-free, as no sliding friction occurs. Compared to the Dual Direct escapement, it offers several advantages: it rotates more slowly, which makes it compatible with a faster-beating balance at 28,800 vibrations per hour, is highly reliable, and delivers the impulse close to the balance’s point of rest – allowing the balance to swing freely for most of its cycle.

The lift angle was also reduced from 70 to 36 degrees – a figure that surpasses the approximately 50 degrees of the Swiss lever escapement.

In January 2025, Rolex was granted two patents relating to a new escapement. Both follow the general principle of the Dual Ulysse escapement, which is cited as a reference in the patent documents.

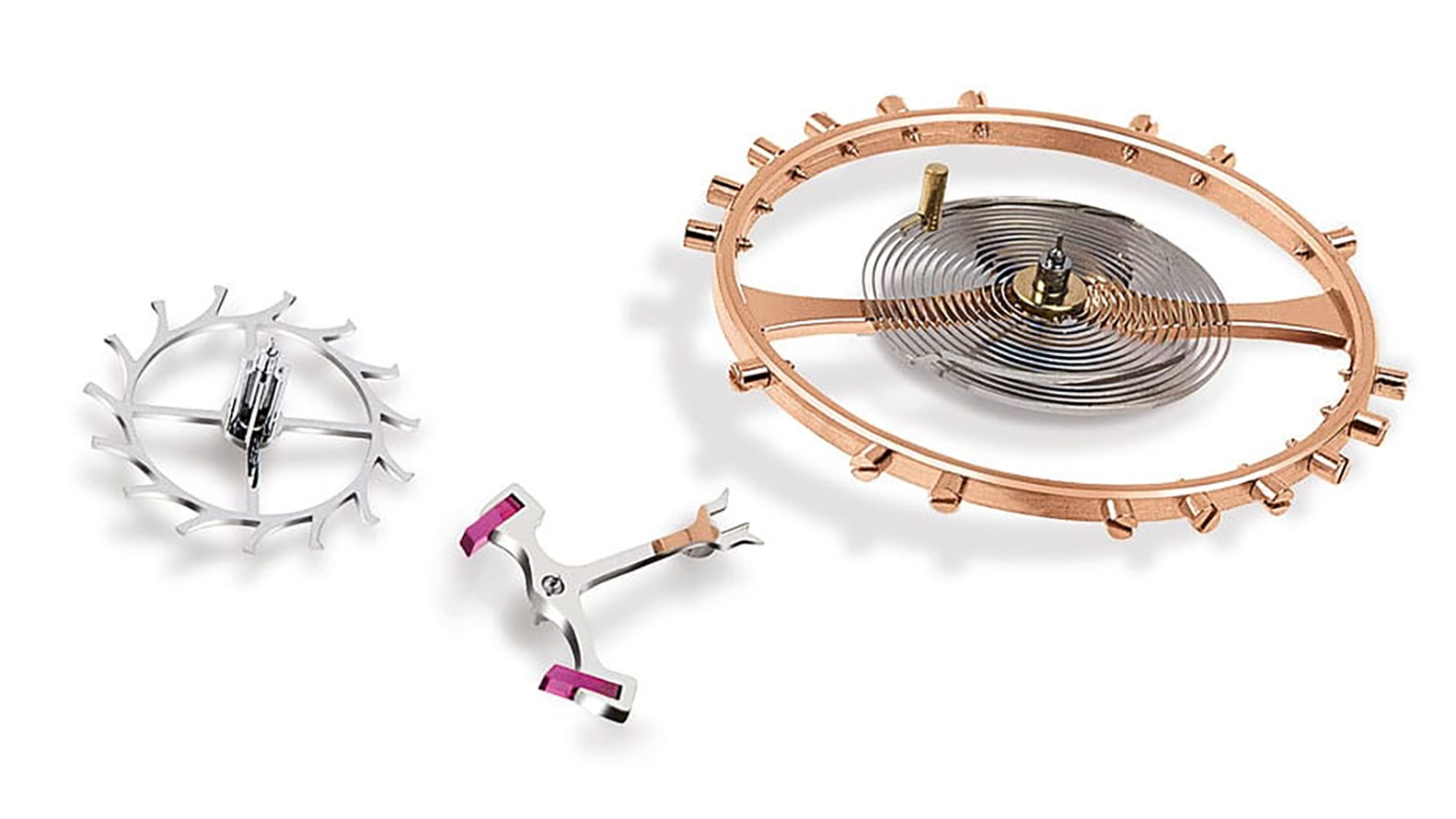

The version used in Rolex’s new Land-Dweller draws on the design of the first Ulysse escapement, in which each escape wheel has five extended teeth – though in Rolex’s version, these teeth are asymmetrical. They interact with the balance via a central lever and are responsible for both locking and impulse transmission.

The outer faces of the lever’s forked tips halt the escape wheels via the extended tooth, while the inner surface delivers the impulse. This takes place in a manner similar to gear teeth, using the pointed tip of the long tooth to avoid any sliding friction – meaning the Rolex escapement should also function without lubrication.

One advantage of Rolex’s design: the central lever is significantly larger, which means it does not require such tight manufacturing tolerances and is therefore easier to produce than Ulysse Nardin’s version. In addition, the outer faces of the fork are slightly convex, making the escapement less sensitive to shocks. It may even be possible to do without limit pins to constrain the lever’s motion.

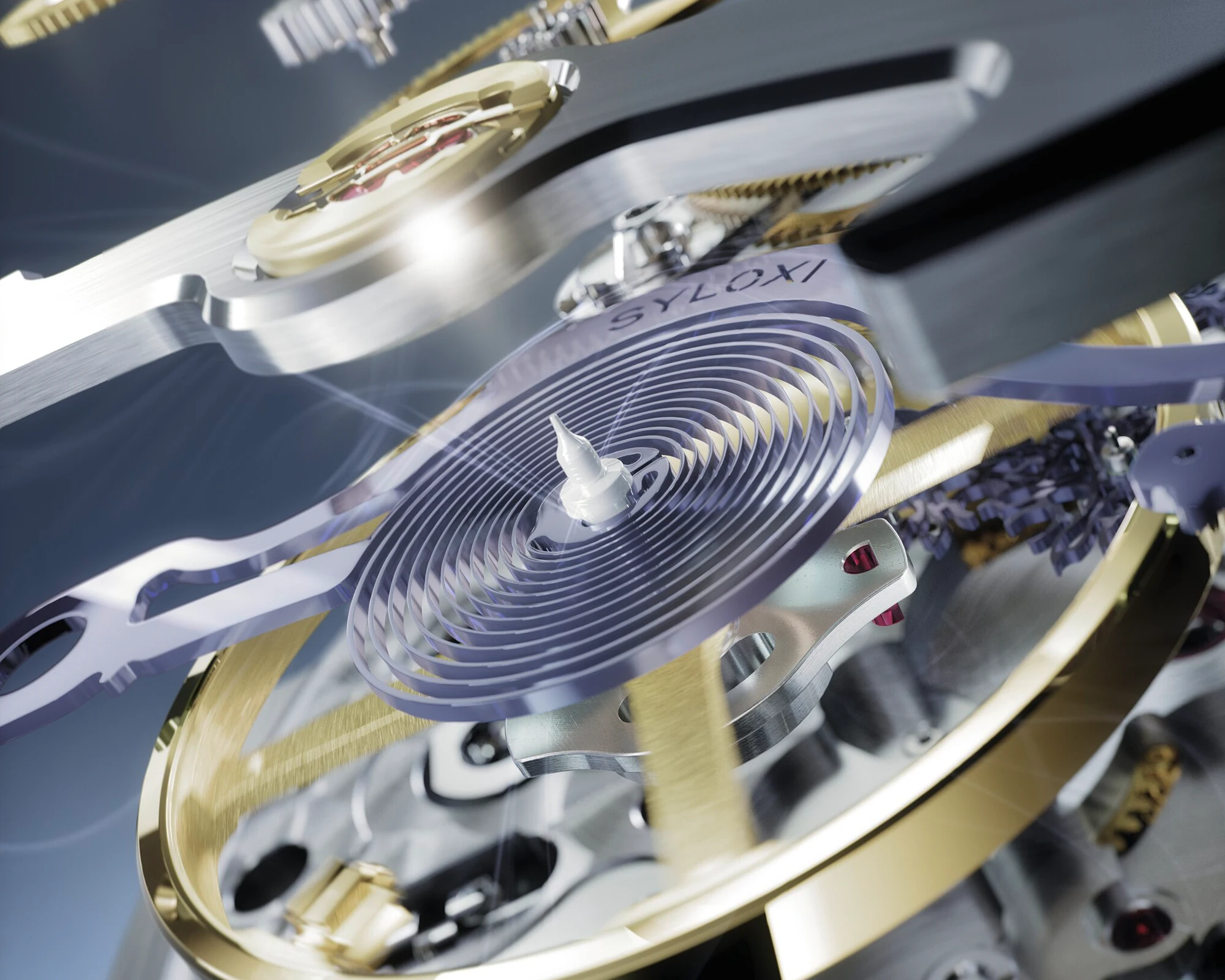

Since no pallets are used and the escape wheels must be extremely lightweight and precisely shaped, the system – like the Dual Ulysse escapement – is realised using silicon wheels manufactured through deep reactive ion etching. The material also compensates for the added friction and inertia of the second escape wheel. Thanks to its dual impulse delivered near the balance’s point of rest, the escapement is self-starting. The mechanism is reportedly capable of operating with high-frequency movements, even up to 10 Hz.

Until now, Rolex has been relatively conservative in its use of materials like silicon. The silicon hairspring, co-developed with Patek Philippe and the Swatch Group, has only been used in the small calibre 2236 for women’s watches and in calibre 7140 for the 1908. Elsewhere, the brand continues to rely on the Parachrom hairspring, made from a proprietary metal alloy. Even in the Chronergy escapement, Rolex has stuck with traditional metals – despite the fact that using silicon could have reduced the weight even further.

The second escapement patented by Rolex has not yet been implemented. It is of a more traditional design, and the two escape wheels could likely be produced from metal using the LIGA process. While the central lever closely resembles that of the first Rolex patent, the escape wheels differ significantly: instead of integrating all functions on a single level, the mutual drive is transferred to gears positioned on a lower plane.

Does this offer any advantages? Not really. While it would indeed allow the escape wheels to be made from metal, the additional gear stage would increase weight, and the lever would still need to be manufactured from silicon, since its shape cannot accommodate ruby pallets.

Whether this escapement is a viable option for the future – or merely intended to mislead potential competitors – remains open to speculation.

The fact that the Swiss lever escapement has become the dominant system does not necessarily mean it is the best. It has clear limitations. Thanks to visionary watchmakers and inventors such as Breguet and Daniels, the pursuit of better alternatives has continued. Today, new materials and manufacturing technologies are enabling systems that were previously impossible to realise.

Omega succeeded in industrialising a lubrication-free escapement with its Co-Axial system and producing it on a large scale. Now, Rolex is poised to manufacture a lubrication-free escapement in significant quantities as well. It is to Rolex’s credit that, despite its dominant market position, the company continues to innovate – and turns that innovation into tangible results.