At the launch of the new Wempe Signature Collection x Ulysse Nardin Diver NET in Berlin, we did a reality check with the watch at the pool.

Jaeger-LeCoultre, often dubbed the ‘Watchmaker of Watchmakers’, has a long history of supplying parts to esteemed brands like Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Cartier. Today a fully integrated manufacture producing some of the most coveted and complicated luxury watches in the world, this legacy of expertise is upheld by the 180 crafts that continue to be practiced at the horology house in the 21st century – each contributing to the unparalleled precision of its watches. Swisswatches recently paid a visit to the manufacture to discover how the brand came to instil precision into every single facet of its creations.

If we go back far enough, the journey of precision at Jaeger-LeCoultre can be traced right back to 1558, a good two centuries prior to the manufacture’s foundation. As the persecution of Huguenots (French Protestants) intensified, a young Pierre LeCoultre sought refuge across the mountains in Geneva, where Protestantism was well-established under theologian John Calvin. Hearing of the flourishing businesses and fast-developing metallurgy industry in the iron-rich Vallée de Joux, LeCoultre soon made the move to the remote valley.

Before heading to the manufacture itself, we spend an afternoon exploring the valley with a local guide, who educates us on the history of the Vallée de Joux. From an anthropological perspective, it is interesting to observe how the location and volatile climate here has affected its inhabitants. Extreme isolation – anyone who has visited will know of the winding roads and high mountains separating the valley from Geneva’s Lac Léman to this day – alongside harsh weather shaped its locals into a patient, enterprising, and rather stoic population. These traits remain instilled in its locals – and thus watchmakers – to this day. Interestingly, of the 6,000 current inhabitants in Vallée de Joux, over 1,200 are employed at the Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture.

But returning to the past: Pierre LeCoultre settled here in the Vallée de Joux, gaining a reputation for his impressive literacy. Following his death, his son made a name for himself by building a chapel in 1612. The chapel marked the very birth of the watchmaking town of Le Sentier, where the Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture is based today.

The following year, a calamitous forest fire annihilated much of the valley’s industry. As locals looked for new avenues of income, small artisanal enterprises began to pop up – one of which was clockmaking, already an established craft in Geneva. It also served farmers throughout the summer months; today, visitors to the valley can stop to admire the remaining watchmaker-cum-farmhouses, recognisable by their large double doors for cattle, in combination with their distinctive upper row of several windows. These windows would allow locals to work on producing watch components throughout the long, dark winter months. Today, of course, the Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture is a light-flooded complex with vast glass windows and chic wooden finishing. Yet the pastoral views outside – quaint wooden houses, softly lowing cows, fickle weather and verdant pines – remain much the same.

By the 1700s, watchmaking was flourishing in the valley, not least thanks to the recognition of watchmaking as a profession in 1723, as well as the granting of commercial and industrial autonomy to the local artisans in 1749. Many parts made in the Vallée de Joux began to be exported back across the mountains to Geneva. This brings us to the most important member of the LeCoultre clan in our journey to precision: Antoine LeCoultre.

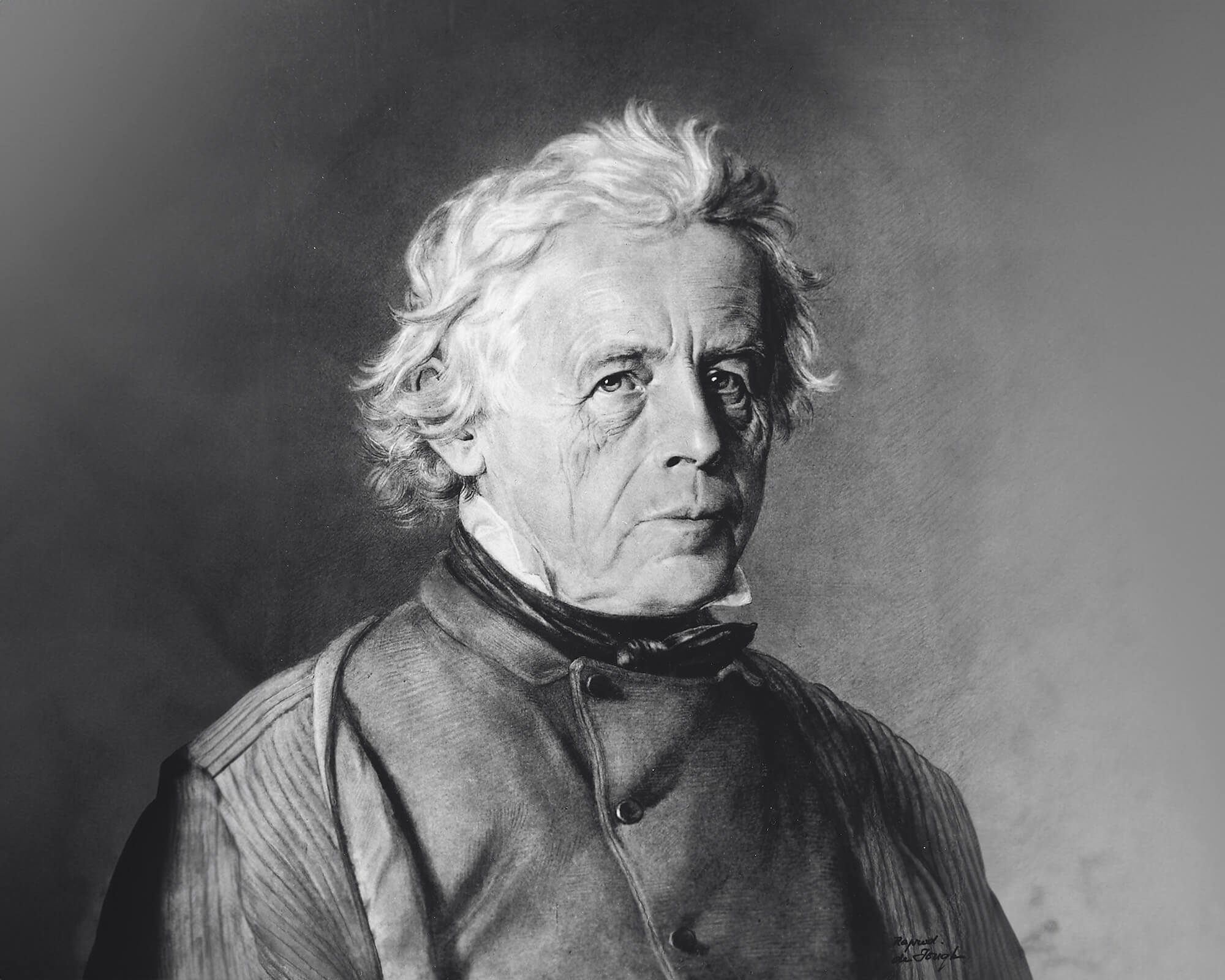

Antoine LeCoultre

Watchmaker Antoine LeCoultre was a keen inventor with a penchant for precision. In 1830, he invented a machine for cutting pinions, aka small but very important gear wheels. For the first time, components could be produced consistently, identical in shape and matching to exact specifications. Today, his ground-breaking machine sits in the Jaeger-LeCoultre manufacture’s Heritage Department, which we take a look at later. Antoine LeCoultre went on to develop precisely calibrated cutting and stamping machines, allowing him to cut smaller components than had ever been seen before.

In 1833, Antoine transformed part of his family barn and forge into a functioning watchmaking workshop, christened LeCoultre & Cie, and promptly employed five watchmakers. As his business flourished, his dedication to precision remained staunchly at the heart of his work. In 1844, he brought forth another significant invention in the form of the Millionometre, which became the first device capable of measuring a micron, opening up new possibilities in the realm of miniaturisation. The Millionometre would go on to serve as the standard for precision for the next half century. The groundwork for LeCoultre’s precision was well and truly set.

Under Antoine’s leadership across the mid-18th century, watchmaking in Le Sentier flourished as the visionary went on to develop ever more ambitious watches, from chronographs to calendars. Other established maisons in the valley and beyond also turned to LeCoultre for various parts, earning the atelier the coveted title it holds today: ‘Watchmaker of Watchmakers’.

In 1866, Antoine LeCoultre and his son officially founded the Vallée de Joux’s very first established watch manufacture, uniting all production processes under one roof. This structure remains the case to this day. The manufacture, now sprawling over 25,000 square metres, operates as a fully integrated facility where every component is crafted in-house. The manufacture is home to engineers, technicians, and artisans alike.

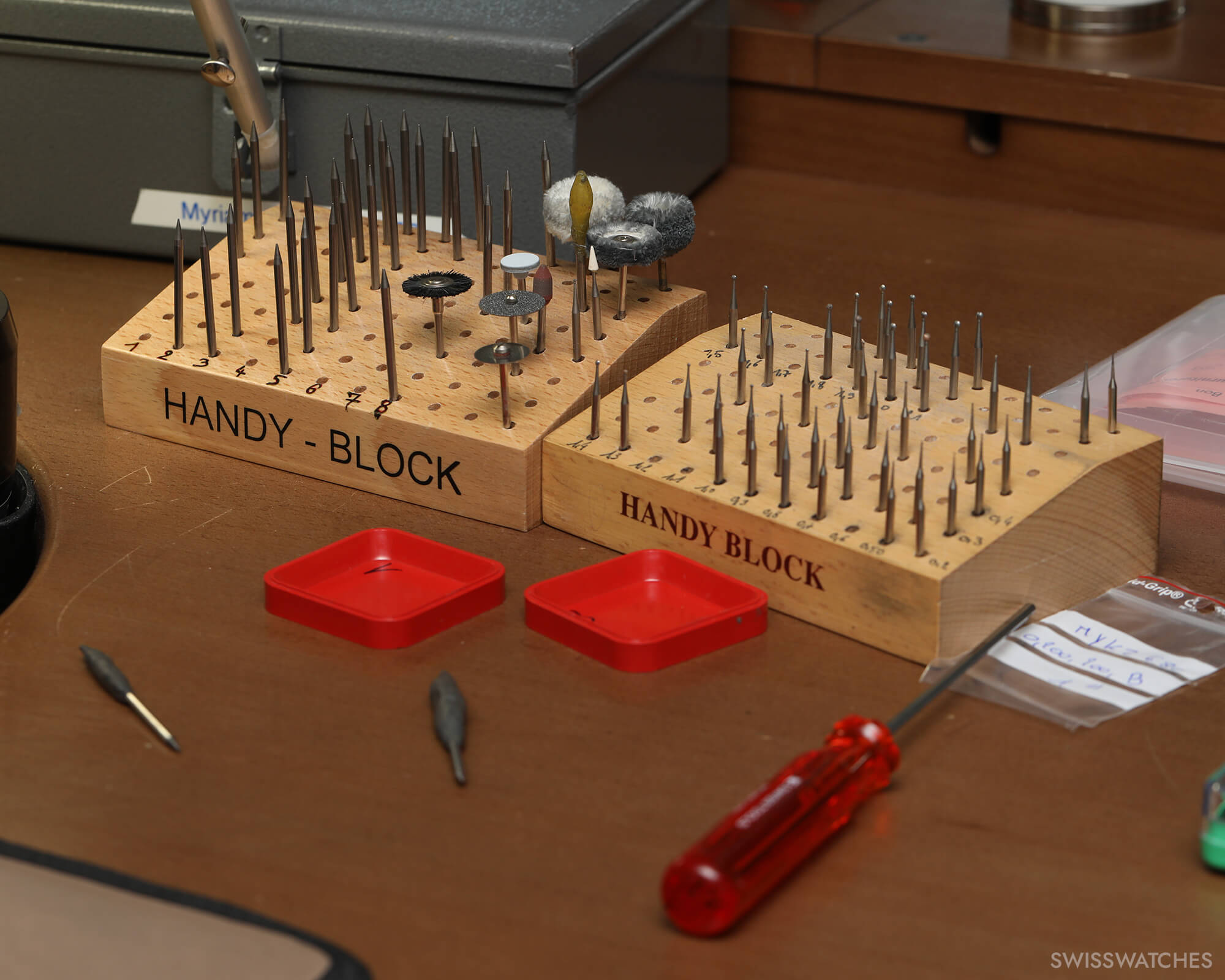

Combining past and present expertise, Jaeger-LeCoultre utilises both ancestral methods, e.g. roulage and bevelling, as well as modern techniques, e.g. milling and laser control. As one watchmaker fervently informs us, precision is not just a value for the brand, but a guiding principle at every stage of production. What’s more, he adds, each meticulously crafted watch passes through approximately 40 pairs of hands.

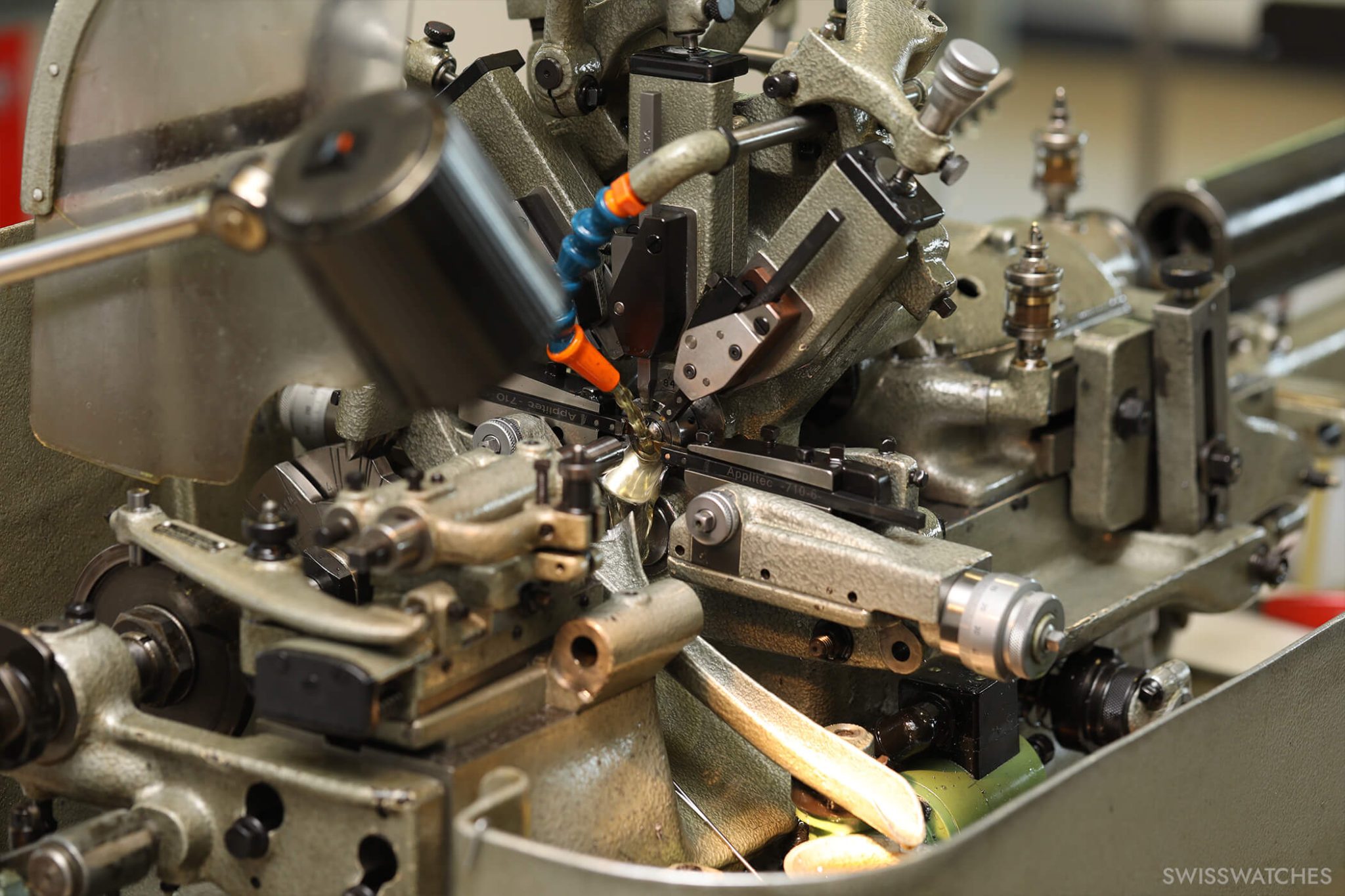

Today, the horology house’s technicians and watchmakers work with micromechanics on a daily basis, measuring components right down to microns (1/1000th of a millimeter). Ever ones to embrace the new as much as preserve the old, Jaeger-LeCoultre was actually one of the first watch manufactures to adopt CNC (computer numeric cutting) machines back in 1982.

Today, the manufacture is home to a vast assortment of costly high-tech precision machines, enabling production processes such as spark erosion, laser cutting, and 3D prototyping. Another hot topic for the brands is stamps, which are used to cut out various components –Jaeger-LeCoultre is currently home to no less than 1,900 stamps that aid the production of its calibres, alongside 15 different materials, encompassing everything from platinum to brass, that may then go into a watch.

During the morning, we partake in the manufacture’s Discovery Workshop in the immaculate Atelier d’Antoine. The focus of our class, unsurprisingly, is precision. Our watchmaking instructor reminds us that a chronometer’s precision is a hallmark of reliability, and every horology house, Jaeger-LeCoultre included, faces four main challenges when it comes to precision: magnetism, shocks, energy, and gravity. In order to tackle these points, every component inside a watch must be carefully produced and regulated, be it through polishing a part or measuring its size to levels invisible to the human eye.

Atelier d’Antoine

Fortunately, the company is pretty adept at pioneering solutions to such obstacles, having created chronometer movements (albeit in pocket watches) since the 1800s. As our instructor tells us, from the first palladium hairspring in 1890 to the Geophysic, aka the first antimagnetic watch in 1958, precision runs through the veins (or indeed components) of every Jaeger-LeCoultre watch – and the proof of this is infinite. Take the 4 Hz calibre 916, launched in 1970, which marked the manufacture’s first foray into ‘high-frequency’ watches back when 2.5 to 3 Hz was standard. Or there’s the Master Compressor Extreme Lab, produced in 2002, which broke new ground with its shock absorbent case and specially protected hairspring.

Managing energy is another element that is crucial for maintaining precision. Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced the first double barrel mechanism in 1981, which notably increased energy storage. A yet more remarkable milestone was the 1,000-Hour Control certification first used in the calibre 889, which transcended the standard Swiss chronometer certification in 1992 and remains in use for all of the manufacture’s watches since 2003. Interestingly, the standard deviation at Jaeger-LeCoultre is actually -6 +1 seconds – because, our instructor informs us, the brand’s clients prefer to be early than late. By contrast, to give a more standard example, Rolex Superlative Chronometers must not exceed -2 +2 seconds per day.

A trip to the High Complications department further illuminates the role of precision across all elements of watchmaking at Jaeger-LeCoultre – particularly in the field of regulating organs, an area in which the brand excels. The manufacture’s complications department is a hub of expertise that is home to around 40 people, including 30 watchmakers, and is dedicated to creating the most intricate, innovative, and highly precise movements.

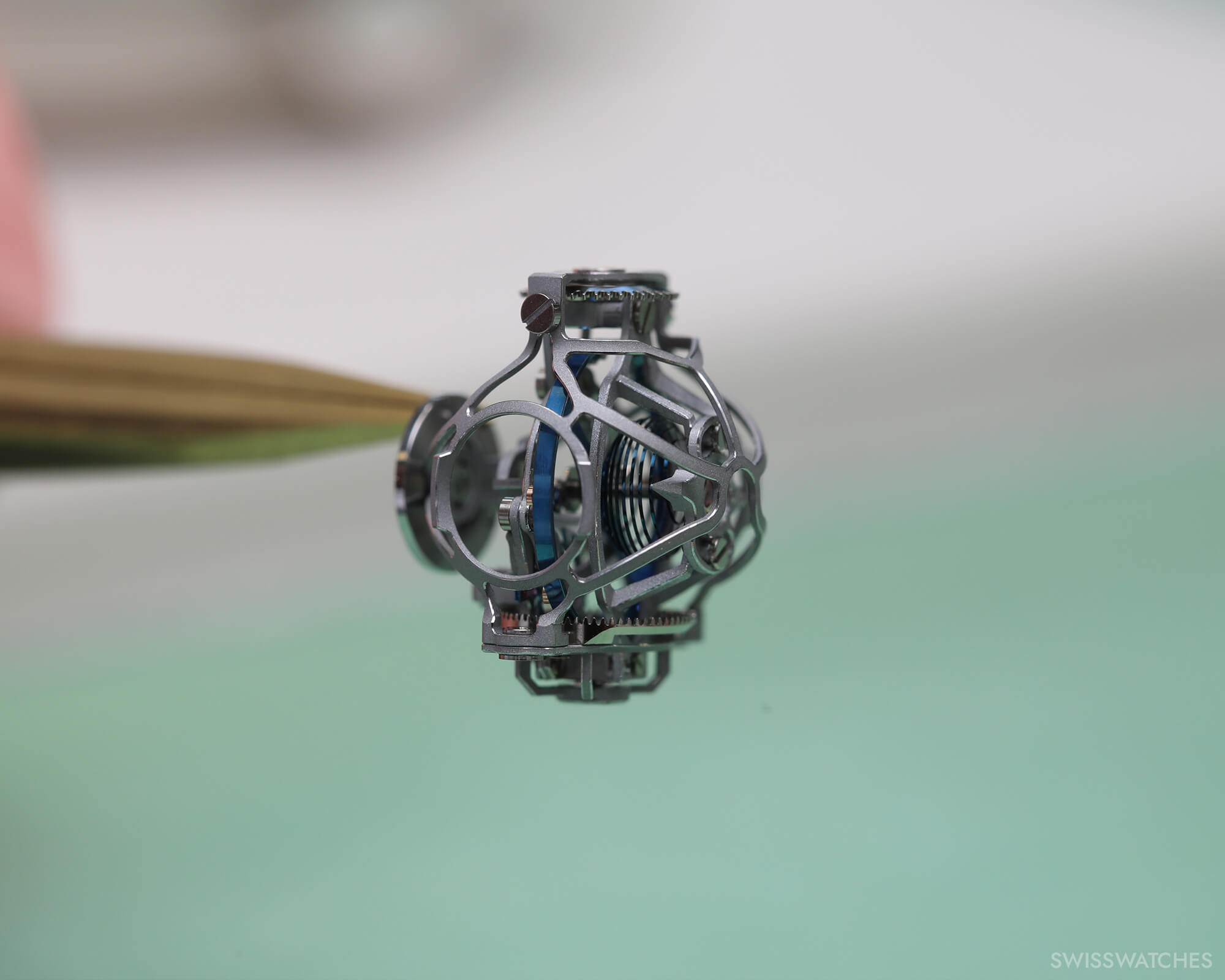

Amidst the chiming watches, minute repeaters, and ground-breaking chronographs, the best-known technical feat of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s innovations still has to be the tourbillon. The brand can take credit for numerous interpretations of the gravity-defying (and thus precision-enhancing) mechanism, from the Gyrotourbillon with its 0.33-gram case, famously housed in the ultra-complicated Master Hybris Mechanica Calibre 184, to the Spherotourbillon, which rotates on two axes to achieve a three-dimensional rotation.

We are also lucky enough to spend some time with the phenomenal Duometre Heliotourbillon Perpetual. This horological wonder marks the introduction of a tourbillon with no less than three axes – and it’s mind-boggling to see in action. The watch embodies numerous watchmaking innovations. For one thing, the patented Duometre mechanism, first introduced in 2007, combines two barrels and two separate gear trains in one calibre, which are connected to a single regulating organ: one gear train to power the time display, and a second gear train powering all other functions. This allows complicated movements that require more energy to maintain their precision to a significantly higher level.

At this year’s Watches & Wonders, Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced three new Duometre models including a version with Heliotourbillon, integrating a cylindrical balance spring and three mesmerizingly rotating titanium cages. As my colleague Nico Bandl explains in his coverage of the Duometre tourbillon novelties, the first cage is positioned at a 90-degree angle to the balance. The second cage is at a 90-degree angle to the first. The two cages are held together by an axis inclined by 40 degrees and complete a full rotation in 30 seconds. The third cage, in turn, is perpendicular to the second and completes one revolution in 60 seconds. The new Heliotourbillon consists of 163 components and weighs less than 0.7 grams. Development lasted five years – however, we learn, this is not an overly long development phase, with some innovations being worked on for a decade before being launched onto the market.

Our journey ends at the Heritage Gallery, a relatively new addition to the horology house. Founded in 2017, the manufacture’s Heritage Gallery showcases the brand’s rich history. Immaculately organised shelves of documents and records, overshadowed by vast white wooden beams, play host to numerous historical and horological milestones, while glassy vitrines reveal a glimpse into the brand’s innovations, from the thinnest mechanical movement housed in a pocket watch, crafted by Antoine LeCoultre’s grandson, to documentation of inventions such as the lever winding mechanism from 1847.

Heritage Gallery

The crowning glory, however, has to be the spiral calibre staircase, allowing visitors to view the brand’s many movements in detail for themselves. Another highlight for collectors is the Atmos wall, comprising two ceiling-high vitrines housing some of the most notable of the ethereal table clocks created to date. Upstairs, where the light-filled attic space plays host to Antoine LeCoultre’s pinion-cutting machine, we observe a couple of watchmakers absorbed in their traditional crafts; one is engaged in thermally blueing a hand, while the other carefully demonstrates the black-polishing process for a movement’s screws. It hits home just how much attention to detail goes into each miniscule part.

Traversing all of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s manufacture in Le Sentier is the equivalent to walking eleven kilometres. No surprise, then, that our short trip has only allowed us to hone in on one (albeit very important) theme for the manufacture. Nevertheless, the time spent here has provided living proof of the horology house’s dedication to precision. From its very history to its intricate interpretations of traditional complications in the modern age, the manufacture is a testimony to the fact that perseverance and precision are a sure-fire path to success.