With the three Top Time Classic Cars, Breitling has created the perfect watches for owners (and lovers) of these legendary sports cars.

The subject of sustainability remains a difficult – and even taboo – topic in the world of luxury goods. Despite arguably being inherently sustainable due to their longevity, Swiss watches do fall into this category of premium products. Therefore, it is the responsibility of those in the industry – as well as consumers – to consider the ethics and environmental impacts of traditional watchmaking.

We decided to take a look at both the good and the more controversial elements of the Swiss watch industry, in the hope of helping you to make an informed decision about which products you wish to call your own. We also spoke with the World Wildlife Fund’s Global Lead for Mining and Metals, Tobias Kind-Rieper, to get an expert environmental opinion.

This week, we kick off our Sustainability Series with an increasingly discussed topic in the industry: the extraction and use of raw materials.

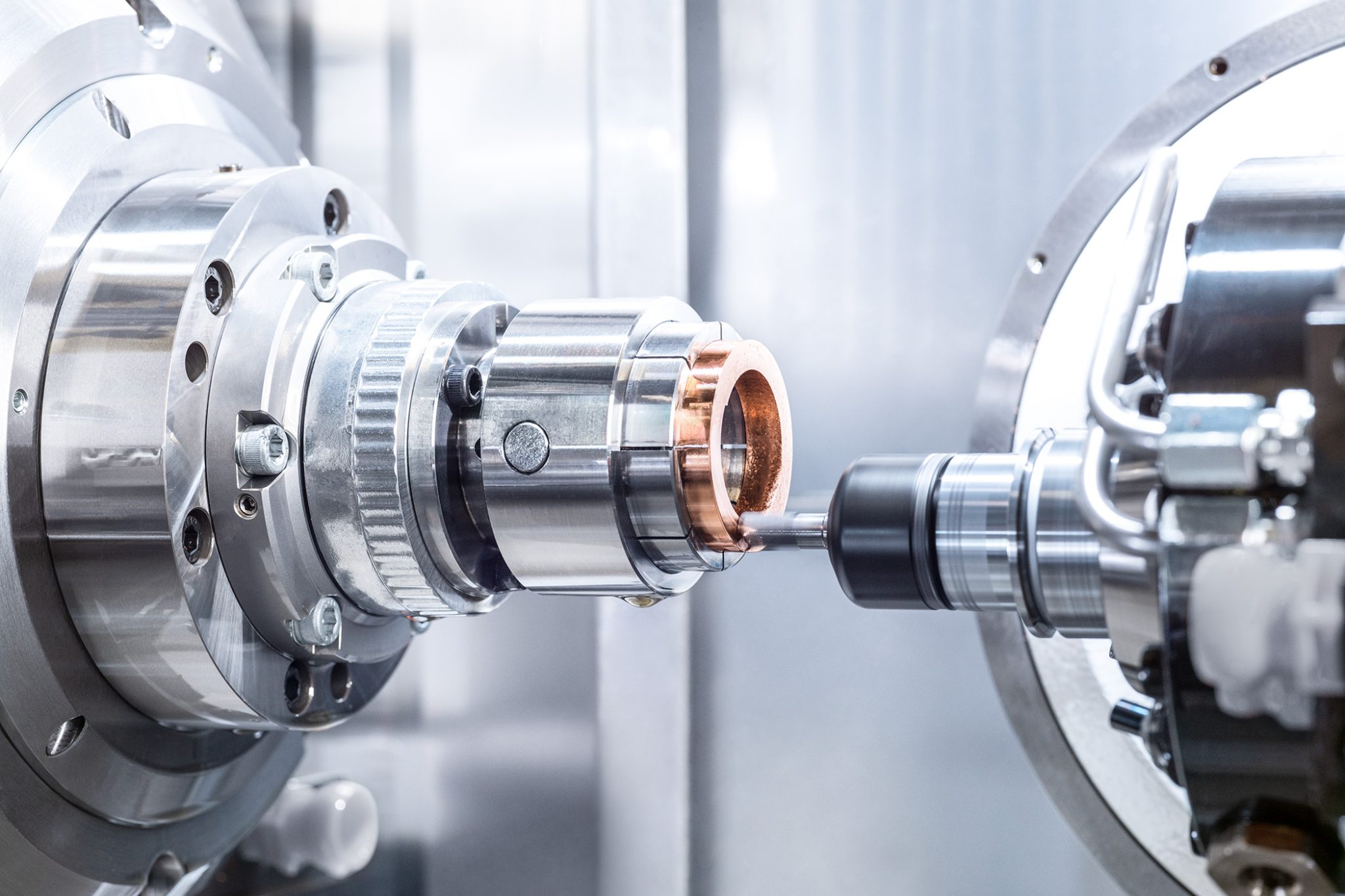

It would be impossible to write a series on sustainability in the Swiss watch industry without taking into account metal mining. So, let’s start with this all-important topic. A key factor to consider when it comes to any metal is that it is non-renewable. When it’s gone, it’s gone. Furthermore, metals aren’t exactly easy to obtain. Aluminium, for example, which is found on many sports watches’ bezels, requires particularly large amounts of energy to be extracted.

The extraction of aluminium, often found on watch bezels, is extremely energy intensive

Extracting metal ore, whether iron ore (the basis of steel), platinum, or otherwise, requires large-scale clearance of land and high energy extraction processes. Additionally, metal ore mining usually takes place in remote locations, leading to high levels of transportation pollution. On the other hand, metal can be continuously recycled; something that is gaining momentum in the watch industry thanks to leading horology houses such as Panerai.

The Panerai Submersible eLAB-ID

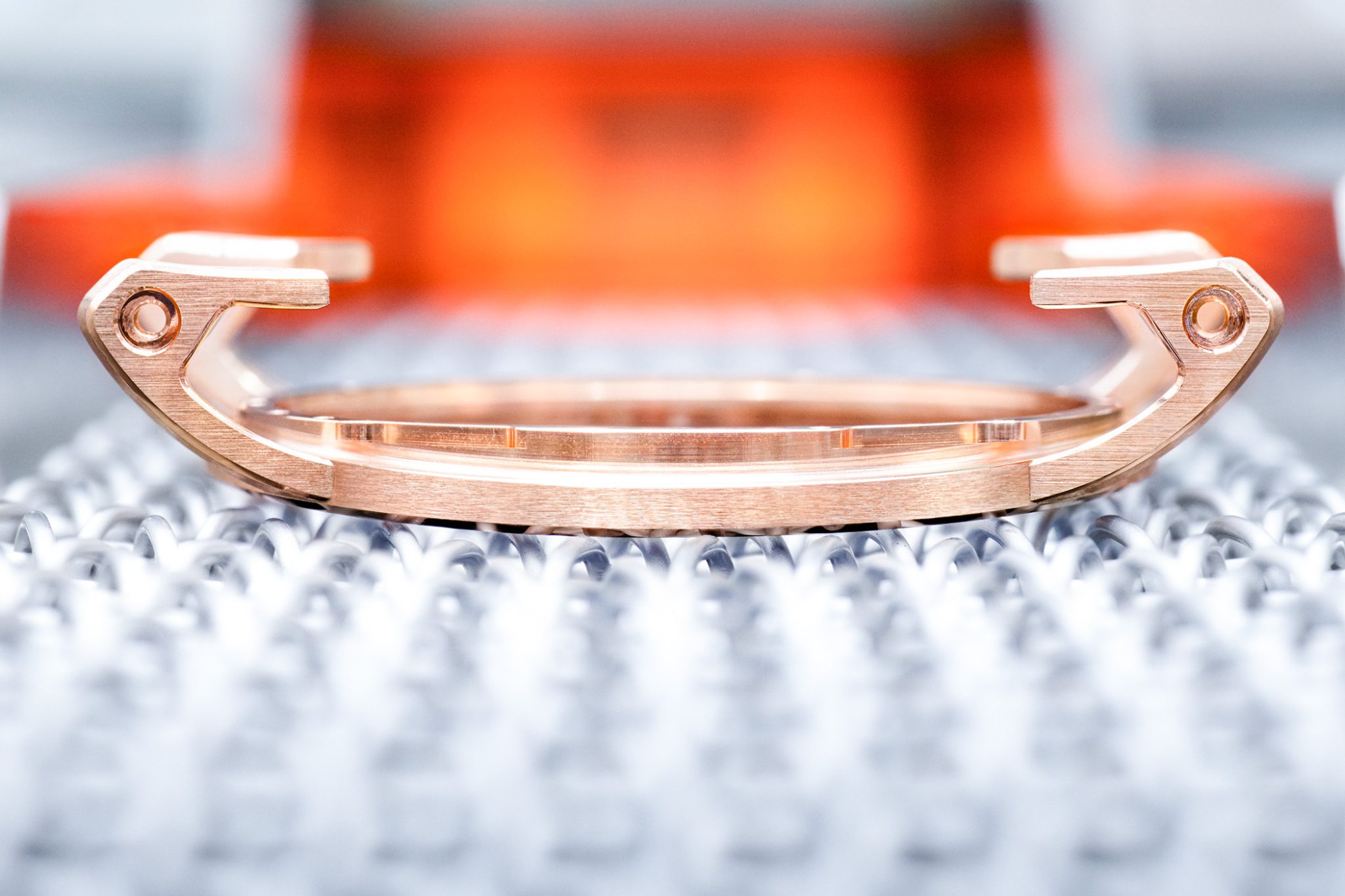

Recycling metal can make a significant difference; recycling one tonne of metal scrap, for example, uses up to 95 percent less energy than what is required to create one “new” tonne of metal from raw material. Additionally, it is worth keeping things in perspective; while the practice of recycling metal is commendable, watches ultimately use tiny amounts of metal in comparison to many other everyday products, from cars to household appliances.

The same cannot be said, however, for gold – a common material in the Swiss watch industry. The precious metal gold requires miners to remove enormous amounts of earth in order to attain tiny amounts. In fact, one tonne of rock holds between only one to six grams of gold. Additionally, there are also numerous other environmental challenges throughout the gold mining process, from pollution to deforestation. Water pollution is a particularly serious matter. In gold-rich countries such as parts of Latin America, Africa, and Asia, water is already scarce, and the toxic substances involved in the process of obtaining gold can play significant roles in the destruction of entire ecosystems.

The environmental impact of gold mines can be severe

This also applies to artisanal and small-scale gold mining, despite it being more encouraged than large-scale mines. Perhaps surprisingly, artisanal and small-scale gold mining is the leading source of mercury pollution in the Amazon. This is currently receiving a high level of attention worldwide, as several species of the local freshwater dolphin are dwindling in numbers.

According to Tobias Kind-Rieper, WWF’s Global Lead for Mining and Metals, the damages of such mining also affects indigenous and other locals. “We can see that mining has already affected up to two or three million people with high mercury contamination,” he says. “The health of many indigenous people is under threat. We have seen so many pictures of pregnant women being affected through contamination after they eat fish. There should be no mining in protected areas. But if mining is to be done around indigenous communities, it needs to be done responsibly.”

Tobias Kind-Rieper – Global Lead Mining & Metals WWF

Given these disheartening facts, it’s not surprising that according to a survey by Deloitte last year, 50 percent of consumers now consider sustainability when buying a watch. Many are willing to pay more in order to have a product that can demonstrate its supply chain with transparency. Nevertheless, a number of brands within the Swiss watch industry still decline to share origins or statistics regarding their gold. While disconcerting to consumers, this is not necessarily to be seen as dubious.

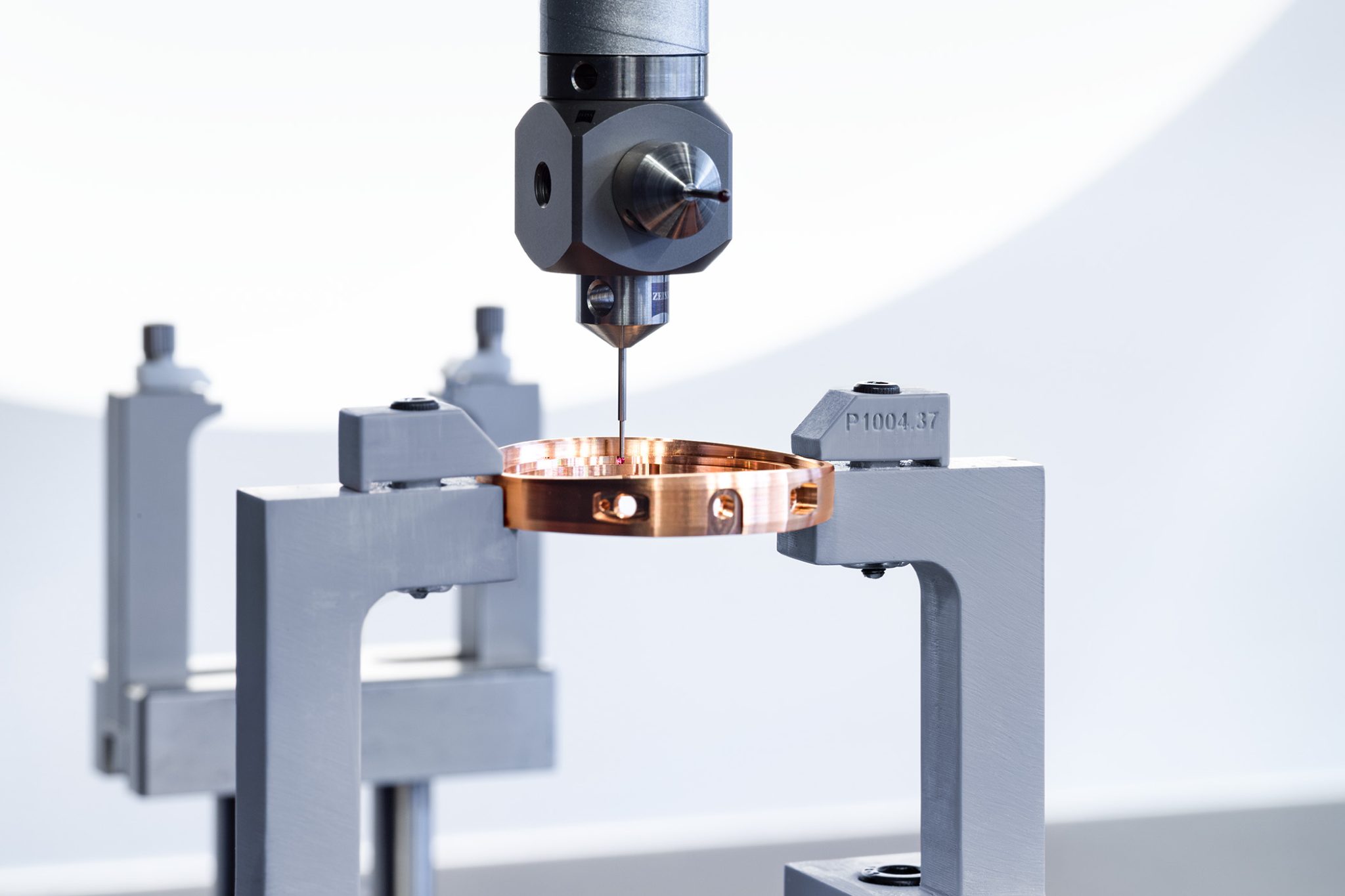

A number of Swiss watch manufactures are cautious about sharing production statistics

One reason that some manufactures do not share information about their gold is that competitors may use these figures to estimate levels of production. Watch manufactures are also notoriously secretive. Given watch companies’ exclusive approach, many people are not aware that use of recycled gold is far more common than one might expect. Companies also keep quiet because inevitably, in the world of luxury goods, revealing that one reuses or recycles gold can even deter customers. Nevertheless, the air of secrecy is undoubtedly something that needs to change. After all, according to WWF 2018 report, between 60 to 70 percent of globally mined gold travels to Switzerland to be refined, with the watch and jewellery industry using over 50 percent of all annual gold production. However, although it is being refined in Switzerland, it is not necessarily being used by Swiss companies but rather sometimes passing through for refinement.

Between 60 to 70 percent of globally mined raw gold travels to Switzerland to be refined

As of 2018, about 67 percent of newly mined rough diamonds produced globally were used by the watch and jewellery industry. Nevertheless, few consider how manufactures obtain their diamonds. Even fewer are aware of how suppliers extract them. Diamonds lie about one hundred miles underground in a rock called kimberlite. Inside this rock, heat and pressure from the earth naturally crystallise carbon into becoming diamonds. The gases produced from nearby volcanoes bring them closer to the surface very quickly. However, extracting these diamonds is a hugely laborious process, but it reaps its rewards through its incredibly high and stable value. In fact, diamonds are often considered to be a more stable investment than both silver and gold.

As a result of their consistently high value, the 90s saw a wave of civil wars break out over these so-called “blood diamonds”. Countries such as Sierra Leone and Angola were fighting violently over highly lucrative land rich in kimberlite. This is why, in 2000, the international community (now 83 governments in total) came up with the Kimberley Process, establishing a zero-tolerance approach to use of conflict diamonds.

The Kimberley Process requires the issuance and authorisation of a certificate for every single rough diamond up for purchase. Switzerland has been a part of the Kimberley Process since 2003, and the Ethics Code of the Swiss Watch and Jewellery Industry, adopted in 2006, specifically refers to the rules of the Kimberley Process. That said, the Kimberley Process boils down to a government’s role in rough diamond trading. This is potentially problematic given that the Swiss watch industry tends to work with polished diamonds. Therefore, watch brands are technically not directly responsible for their diamonds’ sources.

Switzerland has been a part of the Kimberley Process since 2003

The majority of prominent Swiss watch brands are members of the Responsible Jewellery Council. This primarily aims to transform supply chains so that they become more responsible and sustainable. The RJC sets clear standards for pretty much all mainstream minerals and metals in the Swiss watch industry. Seeing that a company is a member of it can help to assure customers that they are purchasing products from an ethical brand.

So how effective really is the RJC – and can consumers trust it? I put this question to Tobias Kind-Rieper, WWF’s Global Lead for Mining and Metals. “Certification is always good for companies in general,” he says. “However, our approach is that certification is only one part of it. In general, when it comes to responsible mineral sourcing, certification often has problems in implementation, e.g., when it comes to trusting the source. There is always something a certification can’t 100 percent cover. It is important that companies ensure traceability and responsible sourcing along their supply chains, which often need measures beyond certification.”

“Company sustainability reports should be publicly available,” Kind-Rieper continues. “For the consumer, it is important to have the possibility to find out what a company’s audit says and what a company does to minimise the negative impact on people and the environment. When investing in a new watch, it could well be worth taking the time to research your chosen brand individually.” We’ve got you covered on this topic – in Part 2 of our Sustainability Series, we will introduce you to some of the brands acting as role models within the Swiss watch industry.

The Deloitte Swiss Watch Industry Study 2020. Deloitte, 2020. Accessed 5 July 2021.

Power Up Switzerland: Improving potential and enhancing competitiveness. Deloitte, 2020. Accessed 5 July 2021.

A Precious Transition: Demanding more transparency and responsibility in the watch and jewellery sector. Environmental rating and industry report 2018. WWF, 2018. Accessed 5 July 2021.