We introduce you to the best chronograph watches with mechanical movements on the market at every price point.

Something of a curse within the Swiss watches industry is that almost every horology house lays claim to being the first of their kind: a record-breaker, an inventor, a pioneer. The same applies to the field of chronograph watches, aka a timepiece that offers precision timekeeping and measurement. And no wonder: it’s an extraordinarily vast area, stretching far beyond its simple definition and well into the annuls of history, technology, and beyond. This article will endeavour to give you the ultimate overview into the world of chronographs, from how to use various functions to the people and watchmakers behind these extraordinarily useful and enduringly popular tool watches.

It was in the early 19th century France that Louis Moinet introduced the world to the first chronograph mechanism. Sculptor, painter, horologist, and confidante of master watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet, his horological creations are not only fine timepieces but also treasured works of art, with various Moinet clocks still displayed across the world, with one even having found its way to the White House. Most importantly for us, however, is that Moinet is the father of the world’s first chronograph.

Credit © Lacotedesmontres

Note, however, this was the first chronograph mechanism – not the first chronograph watch. That would not follow until sometime later. Furthermore, his device gave no indication of the actual time. However, it did offer start, stop, and zero reset pushers. This reset function is particularly of note, although watchmaker Adolph Nicole’s enduringly popular cam-actuated lever, better known as a ‘heart-shaped cam’, which allowed the hand to return to zero, would not be patented until 1862. We’ll get to that later.

Returning to Moinet’s invention: conceived to time astrological events, it measured events to a 60th of a second using a central hand, much as the layout largely remains today. The elapsed seconds and minutes appeared on separate registers, while the hours elapsed appeared in a 24-hour format. The fact that Moinet’s creation had the ability to measure to within one 60th of a second, thanks to its 30-Hz balance wheel, is something of a miracle; its precision for the period in which Moinet was living is truly mind-blowing. Obviously, this mechanism was the first high-frequency movement of the time, running at no less than 216,000 vph.

Credit © Lacotedesmontres

Moinet christened his creation the ‘Compteur de Tierces’, translating to ‘counter of thirds’, as the instrument measured to a 60th of a second. So why is it now called a chronograph, you ask? Well, the etymology of the term ‘chronograph’ lies in the Greek word ‘chronos’ (time) and ‘graphien’ (to write or make notes) – pretty self-explanatory. The person behind this now universally used term was, in fact, a contemporary of Moinet.

Today, it would be a fair claim to say that chronographs are primarily linked to motor racing. Historically, however, their ties lie with the world of horse racing – and this brings us to a long-standing myth that was only disproved in recent times. For many years, it was believed that Moinet’s contemporary, Mathieu Rieussec, created the first chronograph. Quite literally ‘writing’ the time, his box-shaped invention, conceived on behalf of King Louis XVIII in 1821, comprised several spinning discs which, activated via a pusher and distributed via a nib, would drop ink onto the enamel dial when a horse finished a race. A much simpler invention than Moinet’s, and one that came notably later. Furthermore, it was a somewhat unsustainable, bothersome invention: the ink tank needed constant refilling, while the dial needed cleaning after every use. Nevertheless, Rieussec’s device, christened the ‘Chronograph with Seconds Indicator’ was patented in March, 1822, with its ink and enamel system leading to the name ‘chronograph’: literally ‘writing the time’. Thus, Rieussec can at least take credit for the name chronograph thanks to his patent.

Credit © Antiquorum

Despite the obvious superiority of Moinet’s invention, ink chronographs became commonplace, remaining in production for some time. That said, in the years that followed, the field of chronographs slowly but surely progressed. In 1844, as is recounted in the ever-reliable A General History of Horology, the resetting mechanism of the needle of the timer was introduced. In 1870, chronograph timers began to feature not one but two seconds hands, allowing for the simultaneous measurement of two events with different durations, as well as recording two different times and intermediate times. As the aficionados amongst you will know, this is the developed split-seconds (rattrapante) function we know today, headed by the likes of A. Lange & Söhne, and something that we will certainly delve into later in this article.

At this point, we can make the move from the 19th century to the 20th century, as there is one calibre in particular that nicely bridges the two centuries. It belongs to the oldest watch brand trademarked in the International Registry at WIPO: Longines. In 1878, Longines created its first chronograph pocket watch, using the 20H calibre to time horse races.

Credit © Longines

Building on this expertise and heavily investing in timing technology, Longines was able to produce what is commonly regarded as the world’s first wristwatch with a compact-sized chronograph calibre by 1913. Using the now legendary 13.33Z movement with a 29 mm diameter, the mechanism was designed specifically for wristwatches, while featuring a mono-pusher chronograph that allowed its wearer to stop, start, and reset the chronograph while also having access to the time on their wrist. The 13.33Z was a milestone in precision timing history, representing the blueprint for the modern chronographs of today.

It’s interesting to bear in mind that while jewellery wristwatches had become increasingly popular since Patek Philippe first introduced a piece for Hungarian Countess Koscowicz in 1868, wristwatches for men would not become commonplace until the start of the First World War in 1914. Thus, chronographs were among the earlier innovations to make their way into wristwatches. Patek’s first perpetual calendar wristwatch Ref. 97975., for example, would not appear until 1925 – and was also, interestingly enough, a ladies’ wristwatch.

Throughout the 20th century, the popularity of not only horse but also motor car, athletic, sailing, and even aeroplane competitions soared. Each sport relied exclusively upon precision timing. Other devices such as electric circuits and special cameras were developed in order to reduce human error as much as possible. Omega, for example, was first appointed as the official timekeeper of the Olympic Games in 1932, when a lone watchmaker made the pilgrimage from Biel, Switzerland, to Los Angeles armed with 30 split-seconds chronographs. You can read all about the Omega’s phenomenal work in the field of precision timekeeping here.

As racing as well as various technologies took off, other forms of specialised chronographs soon sprung up, easily adapted through various printed scales that appear on the dial. Take the tachymeter chronograph, for example, which features a special scale to compute a speed based on travel time, or to measure a distance based on speed. This remains a hugely popular measurement today thanks to the continued popularity of motorsport, with the majority of chronographs, from the Omega Speedmaster to TAG Heuer Monaco, featuring the useful scale.

To use a tachymeter bezel, start by activating the chronograph function on your watch to measure elapsed time in seconds. Once the chronograph is running, wait for the event you want to measure, such as covering a known distance or completing a specific task. When the event is finished, stop the chronograph. Then, read the tachymeter scale, which is usually located around the bezel of the watch. The number where the chronograph hand points corresponds to your speed or rate. For example, if the hand points to 60, it indicates you were traveling at 60 units per hour, typically in kilometres or miles depending on the unit used.

There’s also the rather similar (albeit far less popular) telemeter, another printed scale on a chronograph watch’s dial, that calculates the distance of both visual as well as audible actions based on time. Used in the likes of radio, weather – measuring thunderstorms’ distance via the lightning and thunder clap is a prime example, it allows wearers to measure the distance directly from themselves to the event. To give a dramatic example, if a bomb exploded and the light reached you first (light waves travel much faster than sound waves), the chronograph could be actuated upon seeing the flash, and stopped upon hearing the explosion. With Greek at the heart of this term, too, ‘telemeter’ is derived from ‘têle’, meaning far, and ‘metron’, meaning measure. One particularly nice example of a telemeter is Montblanc’s advanced 1858 Split-Second chronograph with a handsome dial and telemeter scale introduced back in 2020, using an innovative mono-pusher Minerva manufacture movement.

Indeed, the latter manufacture, purchased by holding group Richemont on behalf of Montblanc back in 2007, is something of a spearhead in the field of chronographs. Founded in Villeret back in 1858, it now offers one of the richest horological histories in the watchmaking field, laying claim to innovations such as the legendary calibre 19.09 (19 lignes/introduced in 1909) with its distinctive V-shaped chronograph bridge. Its design patented as early as 1912, and is now a distinctive characteristic of the watches.

In the 1920s, the manufacture developed one of the first manual winding monopusher chronographs for wristwatches. The chronograph was specifically designed for the wrist, as opposed to a pocket watch. This was possible due to the smaller size of the movement, the Calibre 13.20 (13 lignes). Still featuring the aforementioned V-shaped bridge, it had a column wheel, horizontal clutch, and a balance wheel oscillating at the traditional frequency of 18,000 vph.

In addition to the calibre 13.20, the calibre 17.29 was produced in the 1930s. This was one of the thinnest monopusher chronographs of its time, with a height of just 5.6 mm. At the same time, Minerva also developed stopwatches that could measure to a fifth of a second as early as 1911, and to a tenth of a second soon after. Thanks to this innovative spirit, Minerva was among the first manufactures in 1916 to produce a high-frequency movement, capable of measuring to a hundredth of a second.

But back to chronograph scales and alternative functions: another timing format that might give Moinet’s creation a run for its money (but certainly not outshine it) is the decimeter scale. This scale, used in conjunction with a chronograph capable of measuring to a hundredth of a minute, helps scientists translate time into a decimal format by dividing each minute into 100 parts, typically displayed around the edge of the dial. Once again, we can look to (TAG) Heuer, with Heuer’s ‘Pre-Carrera’ chronographs such as the Ref. 3336 now proving collector favourites. Introduced well before more famous 1960/70s models such as Autavia, Carrera, and Monaco, which define the brand’s precision timing today, the watches were incredibly elegant, to the point of resembling dress watches of the time. That particular reference, by the way, used the famed Valjoux calibre 22 – and we’ll look closer at the integral role of the (chronograph) movement supplier Valjoux a little later.

Ref. 3336(NT), featuring the Valjoux calibre 22.

Credit © Sotheby’s

Another chronograph scale I can’t resist taking a closer look at is the regatta scale, given we briefly mentioned nautical racing earlier. Created for sailors ahead of a yachting race, a regatta timer can appear in variation iterations and designs, although generally using the same colours as a rule of thumb: blue, red, and white. The most famous flyback regatta timer, which we can use to understand the function, is Rolex’s now-discontinued Yacht Master II. Its regatta scale allows the wearer to select a countdown of anything between ten and one minutes, which it then counts down. A typical race will signal its imminent start ten minutes in advance, along with smaller time increments, enabling sailors to ensure their yacht begins at full speed. A regatta scale on a chronograph watch allows the sailors to time this perfectly.

To set the countdown timer on a Yacht-Master II, the wearer uses the Command Bezel (as Rolex calls it). When rotated a quarter turn counterclockwise, the bezel locks the chronograph pushers and engages the mechanism that controls the countdown hand. The countdown hand moves in one direction, and if the wearer continues turning the bezel past the 10-minute mark, it resets to 1 minute and continues from there. This feature allows sailors to set the countdown timer for any duration between 1 and 10 minutes, which is crucial for timing the starting sequence of a regatta. Five, four, three, two, one… Go!

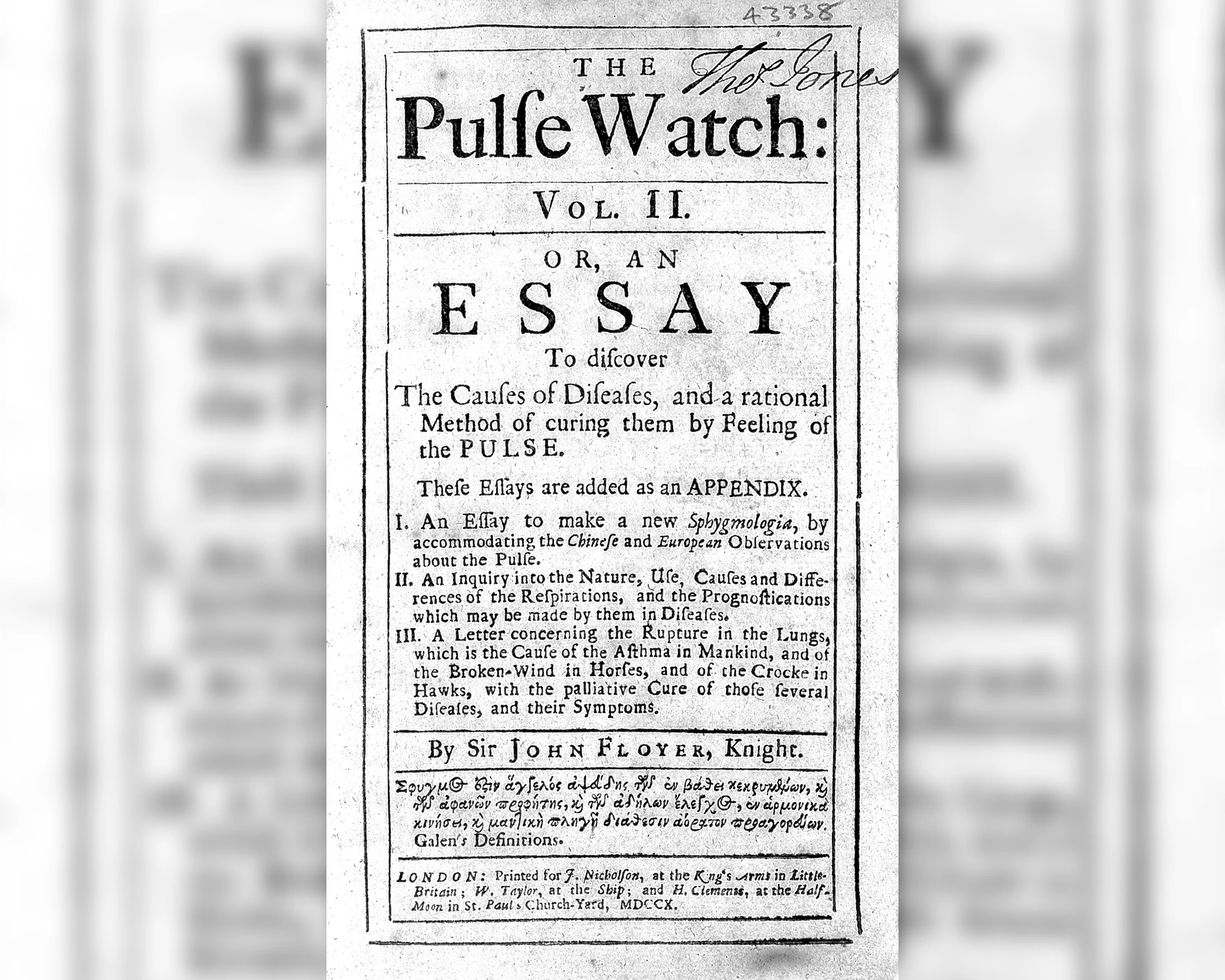

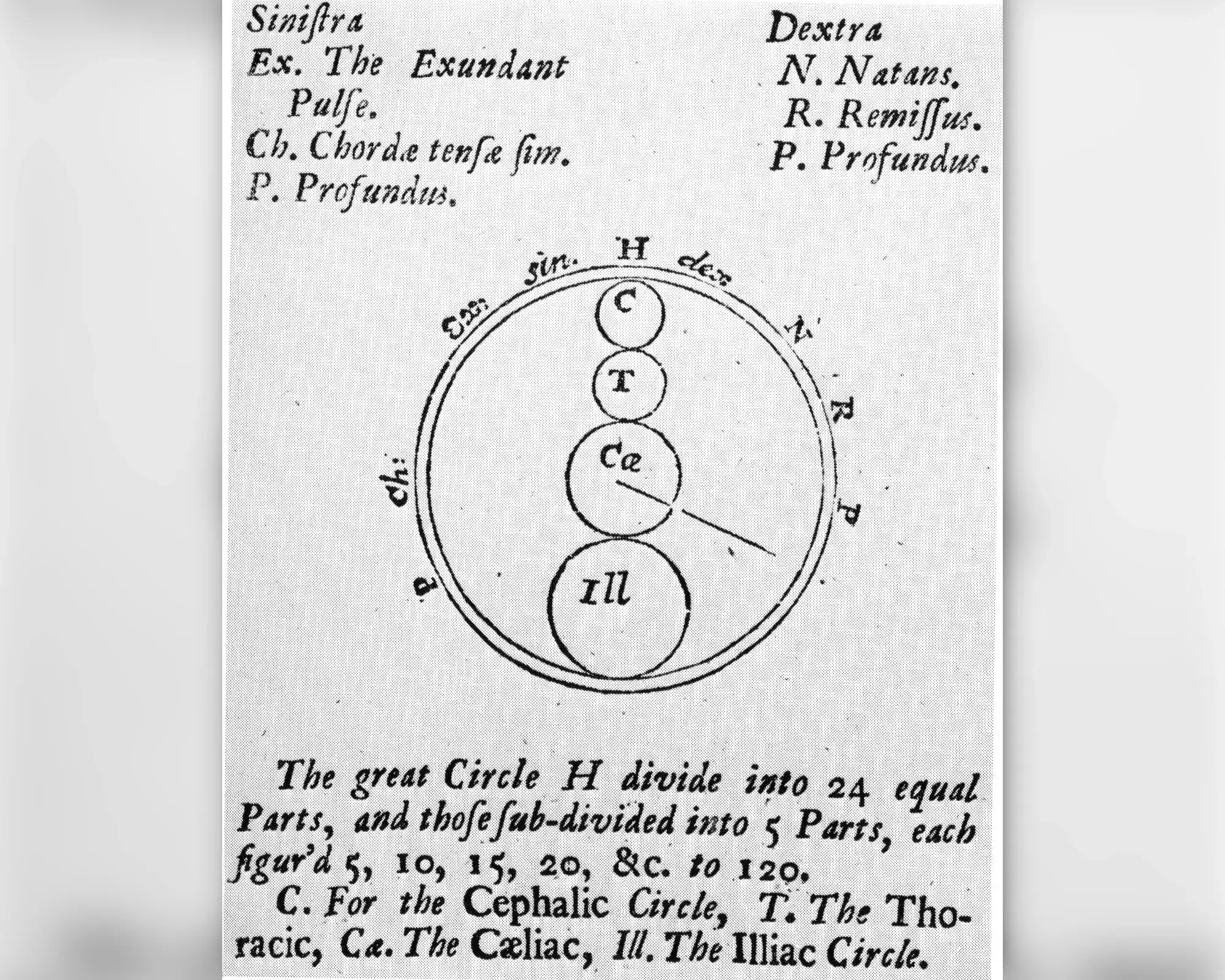

Let’s not forget a fairly well-known yet simultaneously rarely seen scale: the pulsometer, also dubbed the ‘pulsation chronograph’, which once allowed doctors to determine a patient’s heartbeat up until the early 20th century. That said, clarification is once again important, as the pulsometer itself is technically older than actual chronographs: in the early 1700s, an English physician by the name of John Floyer created a portable clock with a seconds hand and lever, which is generally regarded as the first pulsometer.

Credit © The Wellcome Trustees | The Wellcome Trustees

We’re specifically referring to pulsometer chronograph watches, which typically feature a specialised scale around the dial to calculate heartbeats using the chronograph’s seconds hand. The beats are counted until reaching a set number, usually 15 or 30. Highly sought after by collectors today, the pulsometer scale was quickly adopted by key horological brands and even featured on iconic models like the Rolex Daytona and Patek Philippe Calatrava. In fact, a steel Patek Philippe 130 chronograph with a pulsometer fetched over five million dollars at the Phillips Geneva Watch Auction in 2015. Beyond their elegant design, vintage pulsometers are especially prized for their rarity, as most were custom-ordered by doctors rather than being mass-produced. Today, prestigious maisons such as Montblanc’s Minerva manufacture, Patek Philippe, and A. Lange & Söhne continue to produce pulsometer chronographs.

Credit © Philipps

Today, the term ‘central seconds chronograph’ ultimately refers to watches equipped with a centrally mounted seconds hand, driven by the fourth wheel of the movement. This hand can be started, stopped, and reset to zero by pressing a button or knob located on the side of the watch case. Modern chronographs often measure time in fractions of a second, typically fifths, requiring a movement operating at 18,000 vibrations per hour. Some, however, do exceed this frequency. Most famously, the watchmaker Zenith’s El Primero was the first automatic chronograph movement capable of operating at a high frequency of 36,000 vibrations per hour (vph), or 5 Hz, when it was introduced in 1969. This groundbreaking innovation allowed the watch to measure time with remarkable precision, tracking 1/10th of a second – something that previous chronographs couldn’t achieve. Its high frequency made it one of the most accurate mechanical chronographs of its time, and its performance quickly established the El Primero as one of the finest movements in horology. The movement’s significance was further cemented when it was used in iconic watches, including the Rolex Daytona starting in the 1980s, and in Zenith’s own chronographs, cementing its legacy in the world of fine watchmaking.

The process of using a central seconds chronograph is both intricate and elegant. When the user presses the button, an internal lever mechanism engages, allowing the serrated wheels to connect and start the movement of the chronograph hand. Pressing the button again disengages the smaller serrated wheel, stopping the hand precisely. A castle ratchet, a component with ratchet-shaped teeth and raised ‘castle’ projections, locks the mechanism in place to prevent accidental shifts. When the button is pressed a third time, the ratchet and levers work together to release the brake and reset the heart-shaped cam, returning the hand smoothly to zero.

If you ever find yourself conversing with a chronograph expert (although if you’ve made it this far, you’re likely now one yourself), you may hear them refer to a chronograph’s horizontal and vertical coupling system. But what are the technical differences between them – and is one better than the other?

In essence: a horizontal coupling system operates on the same plane as the entirety of the chronograph mechanism. Here, the chronograph central wheel is typically engaged by the addition of a pivoted drive. By contrast, in a vertical coupling system, the chronograph central wheel is directly engaged, and it can shift planes with the help of friction springs. It’s impossible to say if one system is better than the other – however, it can be noted that the horizontal coupling system is less prone to failure and simpler in functionality, whereas the vertical coupling system offers the advantage of more precise engagement.

At the heart of the chronograph mechanism lies the aforementioned heart-shaped cam, the integral component patented in 1862 by Adolph Nicole. This cam is essential for resetting the chronograph hand to zero. The hand itself is mounted on a brass wheel that rotates freely on the central arbour beneath the cannon pinion. The wheel features a finely serrated edge and is driven by a smaller, similarly serrated wheel attached to the pinion connected to the fourth wheel. These wheels are precisely geared to ensure that the chronograph hand completes a full rotation around the dial in one minute.

Although column wheels and cam wheels differ in terms of construction, their indications on the chronograph watch remain the same. When a movement features a column wheel, the precision timing process on a chronograph (start/stop/reset) is controlled by a column wheel. By sensing recesses or elevations on the column wheel, individual levers are moved into the required position. The cam mechanism, on the other hand, consists of a so-called switching cam that can be set to three different positions. Both versions have existed for many years, and both can be counted upon to operate reliably.

Typically, a chronograph has what we call a ‘tricompax’ dial, aka three subdials at 3, 6, and 9 o’clock – although you do also find the occasional ‘bicompax’, which, as the name suggests, has only two subdial counters. But back to the matter at hand: the typical three subdial counters on a chronograph watch can vary slightly from watch to watch. However, the three subdial counters are always of course used to measure different increments of elapsed time. Typically, one subdial tracks the seconds elapsed after the chronograph is activated, often running continuously or starting once the chronograph is engaged. A second subdial records the minutes passed, typically up to 30 or 60 minutes, depending on the design. The third subdial tracks the hours, often measuring up to 12 hours, allowing for the recording of longer intervals.

However, chronograph watches do vary in their layouts occasionally. Take a look at a couple of the most famous chronograph models, the Rolex Daytona and the Omega Speedmaster or ‘Moonwatch’, both of which we’ve already covered on Swisswatches extensively. These two chronograph watches vary in their presentation of timing scales and counters.

The Rolex Daytona and Omega Speedmaster both feature chronograph functions with three subdials, but their layouts and presentations differ. On modern Daytona models powered by calibre 4130, the subdial at 9 o’clock tracks the elapsed hours, the subdial at 3 o’clock measures the elapsed minutes, and the central arrow-tipped chronograph hand tracks the elapsed seconds, using the 60-second scale around the dial’s periphery. In contrast, the Omega Speedmaster has a slightly different layout. The subdial at 3 o’clock displays a 30-minute counter, the subdial at 6 o’clock tracks elapsed hours (up to 12 hours), and the subdial at 9 o’clock is dedicated to running seconds. The Speedmaster’s chronograph seconds hand is centrally mounted, large, pointed, and thinner than the hour and minute hands, and it works in conjunction with the tachymeter scale to calculate speed or distance. The key differences lie in how the two watches use their subdials and central seconds hand, with the Daytona featuring a more traditional approach and the Speedmaster showcasing a distinctive central chronograph seconds hand.

While this might sound complicated due to the range of layouts, mastering the reading a chronograph is not too hard to get the hang of. To read a chronograph, you first need to start the chronograph function by pressing the push-button, typically located on the side of the watch. This will cause the main chronograph hand, more often than not the central seconds hand, to start moving. The chronograph hand will sweep around the dial, marking time in seconds. As explained, the subdial counters are usually used to track minutes and hours. The minutes counter, typically found on a subdial at 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock, records the number of minutes that have passed since you started the chronograph. This counter usually resets after 30 or 60 minutes, depending on the watch. If your chronograph has an hours counter as is typical, it will track longer periods. To stop the timing, press the button again, which will halt the chronograph hand at the point where you stopped it, indicating the elapsed time in seconds. To read the total elapsed time, simply look at the positions of the chronograph hand and the subdial hands to determine how much time has passed in seconds, minutes, and hours.

One feature you may stumble across on a chronograph watch is a Foudroyante – safe to say, once you have this kind of horological vocabulary in your pocket, you’re well and truly a chronograph pro. A Foudroyante is a feature found on a number of chronograph watches, typically indicated by a small subdial counter marked with numbers from 0 to 8. The hand on this subdial completes a full sweep every second, and as it moves, it allows the user to read time in smaller increments, such as eighths of a second. This precise function enables a higher level of accuracy when timing short events. In addition to eighths of a second, some Foudroyante dials are also designed to measure in quarters or fifths of a second. The Foudroyante mechanism is particularly useful for sports or scientific applications, where precise fractional timing is necessary. It was invented and patented, by the way, by our trusty horologist Louis Moinet, back in 1816.

With the Nano Foudroyante, Greubel Forsey rethought the concept of the traditional Foudroyante: the energy consumption of this energy-intensive complication has been reduced by a factor of 1,800 to energy management in the nanojoule range.

Pilot’s chronographs are precision timekeeping watches engineered for the unique demands of aviation, combining precision, functionality, and durability. Designed to be an essential tool for pilots, these watches feature large, legible dials with oversized numerals and high-contrast markers, ensuring they remain readable even in the challenging conditions of a cockpit. Big crowns also often make an appearance as a historical reference to a time when pilots would wear gloves whilst flying, making the watches easier to use. Many also include specialised complications tailored to flight operations, such as flyback chronographs, the aforementioned tachymeters, and dual time zones. More than just instruments of accuracy, pilot’s chronographs can also be seen as manual computers; thus representing a blend of form and function, pilot’s chronograph watches have become popular and often iconic tools for navigating both the skies and the complexities of modern horology.

Let’s look closer at one of the examples just cited: flyback chronographs. The flyback function is a hallmark of many pilot’s chronographs, and it allows for the chronograph hand to be reset instantly with a single press, skipping the need to stop it first. This feature is particularly useful for timing manoeuvres or logging intervals during flight. Tachymeter scales, often engraved on bezels or dials, enable pilots to calculate speed over a set distance, while dual time zones or GMT functions are invaluable for tracking local and destination times on long-haul flights. Breguet’s Type XX was the first chronograph with a flyback function, having been introduced on behalf of French military aviators. These days, the flyback function is often cited as a positive asset for modern chronographs – but how does it work and what’s so good about it?

The flyback chronograph is a sophisticated watch complication that streamlines the stopwatch function by resetting and restarting with a single button press. Unlike standard chronographs, which require separate presses to start, stop, and reset, the flyback mechanism saves critical seconds, making it invaluable for professionals like pilots and divers who depend on precise timing for crucial calculations. An example of this innovation is the RM011 released back in 2007, when watchmaker Richard Mille released a new watch developed in collaboration with Felipe Massa. The RM-011 takes its cues from the high-tech precision engineering of F1 racing cars developed to deliver exceptional performance on the track.

Every flyback chronograph naturally needs a flyback hand. Yet the term ‘flyback hand’ holds dual significance in watchmaking. Primarily, it distinguishes a flyback chronograph, which allows the chronograph to be reset and restarted instantaneously with a single press of the flyback button, from a traditional chronograph requiring separate presses for start, stop, and reset. Additionally, the term describes the swift reset motion of a conventional chronograph or any hand that retrogrades – snapping back to its starting position with an instantaneous action. This characteristic, referred to as the flyback hand, flyback action, or flyback function, exemplifies the precision and engineering finesse in horology, hence the function being viewed as an additional asset in the watchmaking world.

Pilot chronographs provide a nice smooth segue into another key player in the world of chronograph watches: Breitling. The brand plays host to the Navitimer, aka one of the best-known pilot’s watches in the industry with its slide rule function – but its history in the field of precision timing stretches far beyond this model. So far, we’ve touched upon the first few chronograph wristwatches with their monopusher system. However, the world’s first dual pusher chronograph was based on a Breitling patent application from October 1933, adding a separate reset pusher at 4 to pause and resume event timing, and thus defining the typical layout of today’s chronographs. Under Willy Breitling, the Swiss watch manufacture went on to produce the Chronomat, which strived to serve as a ‘tool for scientists, mathematicians, engineers, businessmen’. Patented in 1940, the watch offered up a chronograph for complex calculations, multiplication, division, production timing, interest and exchange rates, rules of three and geometry calculations. It was actually from this Chronomat chronograph model that the famous Navitimer was born. You can read more about the Navitimer model in a contribution from esteemed Breitling historian Fred Mandelbaum here.

Breitling’s biggest feat in modern precision timekeeping is without a doubt its B01 calibre, which features a column wheel. As with a flyback function, this is a coveted quality for a chronograph movement to have. A column wheel controls the action in a chronograph mechanism, governing the start, stop, and reset-to-zero functions. The control mechanism consists of an upright, notched, rotating wheel with ratchet teeth on the bottom and vertical columns on top, which serves as a sliding link to operate the various levers that allow the chronograph to perform its functions. Chronographs with a column wheel are traditionally considered to be finer movements, not least because they offer a more precise and tactilely satisfying feel when the wearer operates the chronograph function.

As with all things in life, while two chronographs might look aesthetically similar, what lies beneath can be vastly different. Watch manufactures have two options when creating a new chronograph watch: a modular chronograph or an integrated chronograph. But what’s the difference? Essentially, a chronograph module comprises a base movement in combination with a so-called chronograph module (or to put simply, an add-on), while an ‘integrated chronograph’ is a complicated movement in its own right, developed from scratch in order to serve as a precision timing watch. Thus, integrated chronographs tend to be considered more superior, and are usually more expensive.

Calibre 6710, manufacturer Vaucher’s integrated chronograph movement (automatic, column wheel)

The famous Heuer calibre 11, a modular automatic movement

Credit © Hodinkee

That’s not to say that there aren’t very respected modular chronograph watches out there: highly sophisticated brands such as Richard Mille and Audemars Piguet have also been known to make use of them, for example in AP’s Royal Oak (Offshore) or Richard Mille’s original and highly coveted RM-11-01. While some brands turn to revered suppliers such as Vaucher for their base calibre, others frequently turn to typical ETA and Sellita movements. The most prevalent chronograph modules are the Dubois Depraz module and the ETA 2894-2, which combines an ETA 2892 with a chronograph module. The former is widely used with ETA movements by Omega and Breitling, and has indeed made an appearance in AP and RM watches.

Essentially, the modular chronograph approach is somewhat similar to the integrated design, but follows a less direct process. Firstly, the base movement is fully assembled, and then the chronograph module is mounted on the dial side. The system relies on a pinion connected to the seconds wheel, which typically drives the seconds hand. This pinion controls the entire chronograph mechanism, unlike the integrated design, where the chronograph operates through the fourth wheel, as mentioned earlier.

Meanwhile, in an integrated chronograph such as Zenith’s El Primero or Rolex’s calibre 4130 powering the Cosmograph Daytona, the regular timekeeping hands operate independently of the chronograph mechanism. These hands are directly connected to wheels driven by the base movement. The chronograph system engages through the fourth wheel, which has an extended pivot holding a secondary wheel. This secondary wheel connects to the chronograph seconds wheel via a rocking intermediate wheel, which toggles the chronograph on and off. The chronograph seconds wheel features a small finger underneath that advances the minute counter wheel every 60 seconds, moving the minute hand forward by one increment. By contrast, a chronograph module operates independently as a self-contained system.

Overall, integrated chronographs are renowned for their stability, with the timekeeping hands and chronograph mechanism operating independently in seamless coordination. Modular chronographs, on the other hand, have a more interconnected design that can introduce minor quirks. For example, starting or stopping the chronograph may cause a slight shudder in the regular seconds hand, a result of the gearing being routed through the module and central pinion. The minute recorder, without a jumper spring, moves in a smooth, continuous motion rather than advancing in distinct, crisp jumps, lending the modular design a different character. One final point is that, as one might expect, a modular chronograph may be more affordable, but the user will likely face more hurdles when the watch needs servicing as modules require complex reassembling, presenting challenges for the supplier.

On that note – where exactly does one stand when it comes to price versus quality? The short answer is that enhancing a simple watch calibre by adding a complication module automatically increases its value. This principle has existed for many years in the watch industry, ranging from simple date mechanisms to perpetual calendars. Respected major watch manufactures often opt for modules because they complement well-performing existing base calibres and are a good way to enable broader model ranges. Thus, ultimately, the question of whether modular watches, especially chronographs, are inferior cannot be definitively answered.

Back at the start of this article, we touched upon Abraham-Louis Breguet’s anticipation of the rattrapante, also commonly known as ‘split seconds’. A ‘split seconds’ chronograph, or more simply put, ‘double chronograph’, can be put to use when someone needs to record two operations at once. This design features two central seconds hands, one positioned directly above the other. These hands are typically crafted from different metals to create a clear visual contrast. When the chronograph is activated, both hands move together in unison. However, pressing a button located on the side of the watch case causes the lower hand to stop while the upper hand continues to measure time. The motion of the upper hand can then be halted using the chronograph’s main push-piece. The lower seconds hand is connected to a brake disc, a crucial component in its stopping mechanism. This disc is clasped by two stop levers when the button on the case band is pressed. The action of pressing the button rotates a ratchet wheel slightly, allowing the tail of a lever to drop into the gap between two ratchet teeth. This action releases the stop levers, which then clamp onto the brake disc, halting the movement of the lower hand.

The connection between the two hands is something of a marvel of precision engineering. A slender, curved spring arm is attached at one end to the brake disc on the lower hand’s pipe. At the free end of this spring arm is a small roller, often made of jewel for durability and smooth operation. This roller rests against the edge of the heart-shaped cam fixed to the upper hand’s pipe. When the lower hand is released, the spring’s tension causes the roller to snap into the cam’s central point, ensuring that the two hands align perfectly, ready to travel together again when the chronograph is reset or restarted.

This intricate mechanism allows the double centre seconds chronograph to perform split-timing functions with precision, making it an invaluable tool for measuring intervals in complex timekeeping scenarios. A particularly handsome and intricately designed example of a rattrapante would be A. Lange & Söhne’s phenomenal 1815 Rattrapante Honeygold from 2020.

A. Lange & Söhne is, in general, one of the absolute masters of the rattrapante mechanism. In 2004, the German watch manufacture introduced the ‘Double Split’, a rattrapante chronograph that, for the first time, increased the measuring range of intermediate and comparative time measurements in a wristwatch from one minute to an unprecedented 30 minutes. 14 years later, A. Lange broke another record with the introduction of its ‘Triple Split’ calibre L132.1. Its additional pair of hour hands increased the time span for comparative time measurements to a phenomenal twelve hours.

The calibre supplier Valjoux, founded in the Valle de Joux village of Bioux and run by two brothers back in 1901, is well worth a mention when taking a closer look at chronographs. The Reymond brothers, then known as Reymond Frères SA, launched their first chronograph in 1914, known as the calibre 22, which was followed by the smaller-sized calibre 23. However, it was under one of the brothers’ sons that the company truly took off, becoming known as ‘Valjoux SA’ in 1929. Following the First World War, the supplier took on formidable clients including the likes of Rolex, Patek Philippe, as well as the recently revitalised Universal Genève. In 1939, shortly before joining Ebauches SA and then being taken over by the ETA manufacture, supplier Valjoux launched a new portfolio of chronograph calibres based on the calibre 23, this time with three counters. This was the all-important calibre 72.

Credit © Revolutionwatch

The Valjoux calibres 23 and 72 were manufactured for more than six decades up until the early-mid 1970s, indicating the highly sought-after column-wheel calibre movements’ decisive role within the Swiss watch industry. While initially activated via a single push button, the calibre 23 movements with two subdial counters were, interestingly enough, fitted to the first chronographs with two pushers created by Willy Breitling in the mid-1930s. The Valjoux 23 took on many forms, including the so-called 230 flyback, the date function 232, and even triple date 23C. Meanwhile, the Valjoux 72, initially dubbed the 72B, integrated a Breguet spiral, and several versions were likewise created. These movements remain highly coveted amongst collectors to this day.

The highly coveted collector favourite Bundeswehr ‘T-only’, reference 1550 SG , a stainless steel flyback chronograph wristwatch with calibre Valjoux 230, circa 1970.

Credit © Sotheby’s

Furthermore, these calibres established Valjoux’s position as an unrivalled chronograph movement supplier in the industry. As production of the 23 and 72 drew to a close, the company began to mass-manufacture the reputable 7736 calibres with cams. Tudor’s very first chronograph, for example, known as the ‘Oysterdate’ or ‘Homeplate’, appeared at the start of the 70s and made use of the Valjoux 7734. Perhaps most famously, the ‘Montecarlo’ 7100 model, still popular amongst Tudor collectors, replaced the Valjoux 7734 in favour of the Valjoux 234 with a column wheel, providing the utmost accuracy. You can read all about Tudor’s chronographs and their use of Valjoux movements in here, as the subject is fairly inexhaustible. Suffice to say, the modern renaissance of Tudor chronographs began in 2017 with the launch of the Black Bay, which uses a movement manufactured in collaboration with Breitling – although, thanks to the recent official opening of Tudor’s Kenissi manufacture, perhaps we can expect a fully in-house chronograph in the near future. Rolex’s sister company already unveiled the ‘Prince Chronograph’ for the Only Watch auction in 2023, featuring the brand-new manufacture column-wheel construction chronograph calibre MT59XX, entirely developed in-house. Excitingly, the gear train bridge of the chronograph features Kenissi’s signature, which is specifically reserved for development phase movements. Exciting stuff!

Since they’re becoming an increasingly hot topic, we can also cast an eye over Universal Genève, which specialised in chronographs from the 1930s onwards. Its Compax watches, for example, reigned for well over three decades and went through many forms. The Compax ‘Nina Rindt’, a collector favourite from 1963 with a white panda tropical dial, used the famous Valjoux 72, as did its successors, the evocatively named Compax ‘Evil Nina’ and ‘Exotic Nina’ produced in the consecutive years.

Universal Genève Reference 885108, known to collectors as an ‘Exotic Nina’

Credit © Oliver and Clarke

A final fact worth noting is that of all the chronographs out there, it is actually the Valjoux 7750 type in its various variants that is considered one of the most service-friendly calibres. This is largely thanks to the minimal number of components and excellent craftsmanship.

When delving into the world of chronographs, especially vintage chronographs, you’re likely to come across a rather charming term: ‘panda dial’. But what is a panda dial? Put simply, a panda dial refers to a specific style of chronograph watch dial that features a light-coloured (usually white or silver) main dial with contrasting dark subdials, typically black. The subdials are often arranged in a way that resembles the appearance of a panda’s face, with the dark subdials representing the eyes and the lighter background resembling the rest of the face. This distinctive design is popular for its high contrast, which makes the subdials easier to read and adds to the watch’s aesthetic appeal. The term ‘panda dial’ is commonly used in the watch world to describe this particular colour combination, which has become iconic in vintage and modern chronograph designs. A ‘reverse panda dial’, as you might suspect, simply means the dial has a dark background in combination with white/light-coloured subdial counters. Obviously, from red hands to contrasting dial colours, legibility plays a key role in the design of chronographs, making it no wonder that the attractive and easy-to-read ‘panda dial’ enjoys an enduring level of popularity.

Reference 6263 ‘Panda Paul Newman’ Daytona | A stainless steel chronograph wristwatch with tropical minute outer track and bracelet, circa 1969

Credit © Sotheby’s

To the outside world, collectors get stuck on the smallest, most trivial of details; a horology house announces a watch design has undergone a 1 mm reduction of a watch case diameter, and online watch forums descend into pandemonium. Yet that’s the beauty of collecting: the devil is in the detail. Another point of contention – or passion, one might say – is the subject of chronograph pushers.

First and foremost, we can categorise all pushers into two main groups: screw-down pushers and pump pushers. Screw-down pushers were initially introduced in order to improve safety for watches exposed to water – not necessarily by being more water-resistant, but rather by ensuring that a chronograph was not accidentally adjusted while underwater. Just a handful of such watches with screw-down pushers would include iterations of the Rolex Daytona (e.g. Ref. 6263), Tudor’s vintage Oyster Prince Date Chronograph models (e.g. the ’Tiger’), as well as iterations of the Porsche Design automatic chronograph, Omega Speedmaster (e.g. ‘Man on the Moon from the 90s), or Breguet’s famous Type XX Aeronavale Aviator’s Chronograph Flyback.

Type XX Ref. 3800ST for the Aeronavale flying squadron

Chronograph pushers take on numerous shapes and forms: rectangular, ‘olive’-shaped, inverted – e.g. IWC’s Top Gun – textured pushers, and, of course, the famous and enduringly charming ‘mushroom pushers’. Over at Patek Philippe, a particularly respected type of pusher would be the so-called ‘tasti tondi’ pushers, as found the prized Ref. 1463. These round pushers are very rare – only around 720 examples of the Ref.1463, for example, were ever produced – making the ‘tasti tondi’ chronograph pushers a perfect example of how seemingly minor details can transform the value of a watch within the collector community.

Patek Philippe ‘Tasti Tondi’, Reference 1463, stainless steel chronograph wristwatch, produced in 1949

Credit © Sotheby’s

With that, our journey through the world of chronographs draws to a close. It’s been a long read (no doubt you timed it with a certain mechanical tool perching on your wrist), and are emerging an expert in the field of precision timekeeping. Should you feel inspired, you can take a read of our article on the best chronographs available at various prices ranges here.