An overview of the Richard Mille Rafael Nadal series and its innovative models that have had a lasting impact on the watch brand.

Many roads lead to Rome, but only one charmingly uses the eternal city as a turning point. This story demonstrates what it means to have driven the legendary 1000-mile race from Brescia to Rome and back yourself. On the wrist, of course: the Mille Miglia collection from Chopard. Strap in for one of the toughest vintage car rallies in the world.

There are experiences that are hard to share and even harder to describe, even though Instagram tries to prove us wrong every day. Among the most moving in my life was the moment of landing in the waters of Antarctica with an inflatable boat in Fortuna Bay in South Georgia, where in 1916, the British explorer and adventurer Ernest Shackleton began his last march to rescue his stranded crew.

Alongside such nature experiences, nothing else comes close at first, and anyone who has ever been on a safari or a dive will surely confirm this. At that time in Antarctica, by the way, I had a Cartier Santos on my wrist, which I thought was appropriate for this adventure, but that’s another story. But there are also man-made experiences that are just as hard to describe as encountering thousands of freshly born seal pups in the wild. This includes my participation in this year’s Mille Miglia as a driver – and that’s what this story is about.

In mid-June 2024, and for the 37th consecutive time, Chopard had invited participants to the start of the legendary 1000-mile race from Brescia to Rome and back. This race, initiated in 1927 by four Italians, was considered the toughest long-distance race in the world for 30 years until a serious accident led to its end in 1957. It was revived 31 years later as a classic car rally.

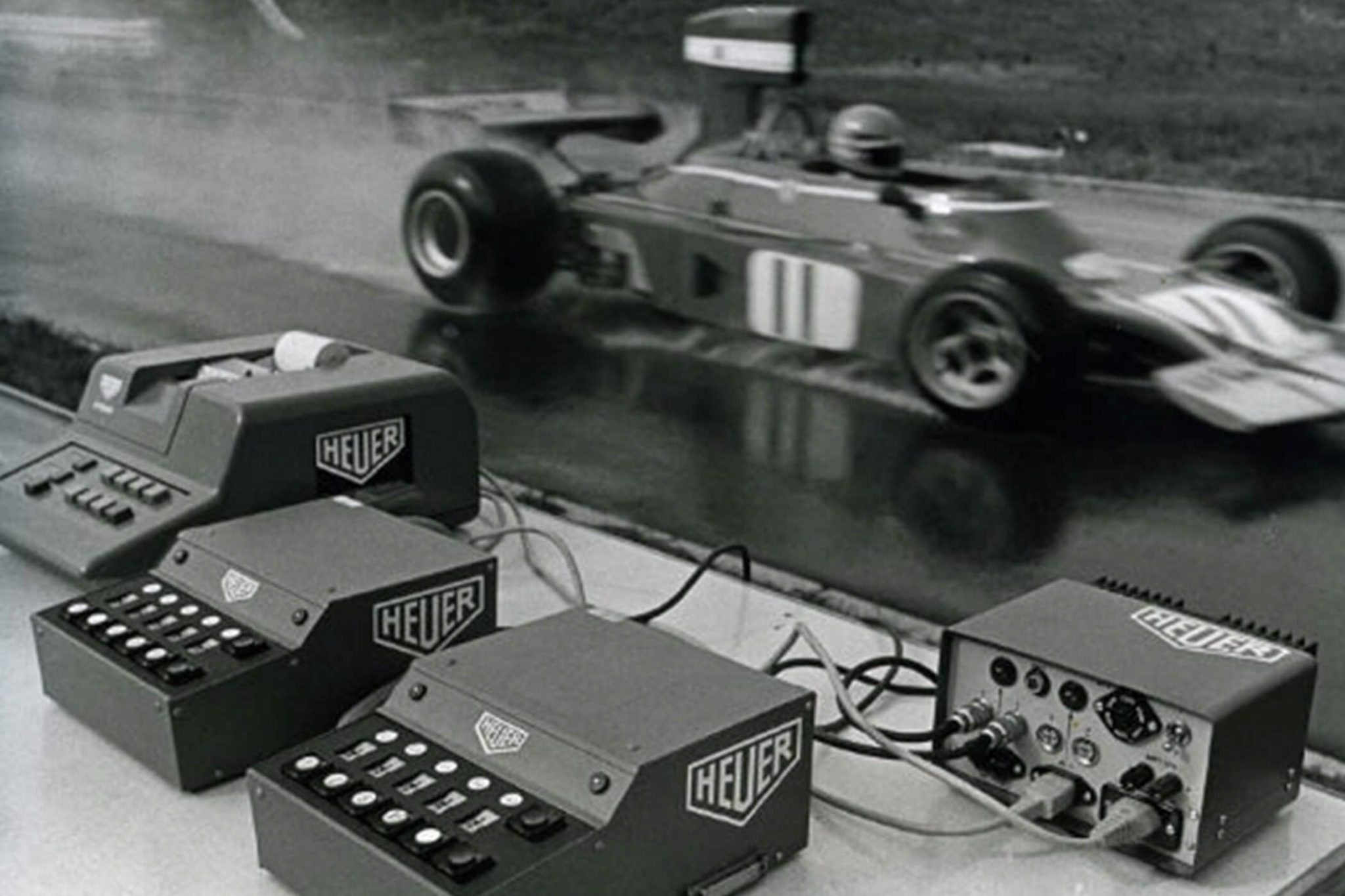

With the Mille, as participants lovingly call it, the longest relationship in history between a family-owned watch manufacturer and a motorsport event is celebrated annually. Chopard has been involved for a full 37 years. For comparison: Rolex, now a foundation, has been a sponsor of the famous 24-hour race at Daytona for 32 years, and the Geneva-based company has been present in Formula 1 for 11 years, but will be replaced by the LVMH Group in 2025. The latter’s subsidiary, TAG Heuer, although the first watch sponsor in Formula 1 and thus longer involved in motorsport (Jack Heuer’s involvement began in 1971 with Ferrari), changed owners twice in the meantime (after the TAG Group, LVMH took over the company).

Completely undisputed and unique at the Mille Miglia is the connection between Chopard’s Co-President Karl-Friedrich Scheufele and the Mille Miglia, in which he is taking part for the 32nd time since 1989, and for the 15th time in the company of his good friend, racing legend Jacky Ickx (he took part twice with his wife Caroline-Marie, in addition to participating with his father and other friends of the Maison). This year, the dream team is competing with Scheufele’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing in Strawberry Metallic with starting number 264. With more than 50,000 kilometers covered, Mr. Scheufele might soon become a racing legend himself: he could now hold the record for the most self-driven miles in this race.

Chopard’s Co-President Karl-Friedrich Scheufele and racing legend Jacky Ickx

The Mille Miglia and Chopard is a collaboration that is unparalleled even in watch models: over the past decades, 36 watches for the Mille Miglia have been designed, creating one of the most interesting motorsport watch collections in the world. Each one of them reflects the essence and soul of this race, whose current advertising slogan “The most beautiful race in the world” doesn’t come from a marketing professional, but from Il Commendatore himself: it is a quote from Enzo Ferrari. But more on the watches later.

Comparing the Mille Miglia to an Antarctic journey may sound puzzling to some readers, as many observers like to think that car racing today is a whimsical summer outing with outrageously expensive vintage cars driven by people with too much money and too much time. What fascinates me about such prejudices is that many things in life seem to be judged by outsiders at least as well as by someone who has actually experienced them. As with foreign policy and football, the rule of thumb apparently is: the bigger a human event, the more people have a very definite, usually negative opinion about it, but especially one that they can’t actually have due to their lack of experience.

I had the opportunity to visit the Mille Miglia as a guest of Chopard in 2016. However, I drove the route from Brescia to Rome in a modern Golf GTI. Anyone who now thinks I can somehow weigh in with the real participants is gravely mistaken. If someone asks me today what is so different about covering this route in a 70-year-old racing car, I would reply: imagine comparing a flight to Italy in an open propeller plane from 1950 with a seat in a Lufthansa Airbus in 2024.

Just having the chance to meet a real Mille Miglia participant is more unlikely than meeting someone who has undertaken a trip to Antarctica: around 55,000 people visit the seventh continent annually, while even considering the 421 participants plus their co-drivers this year, over the past 36 years, you would only come to around 30,000 people in total! In the early years of the comeback, there were less than 100 participants.

Being allowed to participate at all is a good point. Anyone who wants to participate not only needs a valuable old car but also one that really participated in the years when this race was a real car race (i.e., from 1927 to 1957). Now, how many car models do you know from that period? Exactly, meaning: this year, out of more than 400 historic vehicles in the challenge, only 71 are genuine collector’s items that actually started between 1927 and 1957. Among them is one of the cars from our team, but more on that later. Of the few models that existed from this time, the vehicles also need to be largely original. Which is not easy, considering the vehicles are many decades old and had to endure the hardships of a long-distance race multiple times.

Hardships? The Mille Miglia is no joyride; the name itself should instil some respect. Even in the 2024 event, the entire ride will span five competition days. That’s five daily stages and, despite the historical name referencing the original distance of around 1000 American miles, it means more than 2,200 kilometres of racing route to cover. However, the term ‘racing route’ should not be taken literally. Let’s throw in a simple comparison: the well-known Autobahn route from Hamburg to Munich in Germany measures a good 800 kilometres. Imagine driving this route three times in a row, continuously. And not in a car from 2024, but in an open vintage car on country and mountain roads and through small villages. Do you get where I’m going with this?

My Mille begins in Turin. As a complete novelty, the parade will make stops in Turin and Genoa this year. As was last done in 2021 and before that, a total of 14 times, this year’s route will be driven counterclockwise. The route is clear: there will be stops in Turin, Viareggio, Rome, and Bologna before returning to Brescia as usual.

The reason I am not starting in Brescia is simply that Chopard, as the sole sponsor, gets the opportunity to distribute several drivers over the entire race, allowing as many people as possible to experience participating in original vehicles. My journey ends in Rome, the eternal city. Turin charmingly fits the origin of our vehicles: traditionally, Turin, with the Fiat factories, is considered the heart of Italian automobile manufacturing. The options include a racing-green Fiat 1100 Pininfarina from 1950, and an extremely rare open Ermini Sport 1100 from 1952, a vehicle whose chassis also comes from Fiat.

Fiat 1100 Pininfarina from 1950

Even though these vehicles do not have such legendary names as the many participating Ferraris or Alfa Romeos, these cars are extremely rare today. They need a lot of love. And spare parts. Therefore, it is not vanity for each participating duo to have their own mechanic team with them. No one, really no one, can compete in such a long-distance race without a work team. What does that mean? From now on, we will have a four-person mechanic crew available, discreetly following us in the Maserati SUV and digitally tracking us just in case.

Arriving in Turin, I will initially be assigned the closed Fiat with my co-driver. At least a roof over our heads, I think to myself. After all, the Mille Miglia is known for having to drive long stretches in the rain.

The head of the mechanic team is Pietro, whom I will henceforth call Super-Pietro because he fits the cliché of the helpful Italian by the roadside who immediately jumps in to help and whom you always want by your side. Pietro’s last name is Trenconi, and he is not just anyone: the son of a racing family, he makes dreams possible with his company for all those who don’t own a Mille-Miglia racing car. His company is called Classic Car Charter.

Before the race, we had a one-hour video introduction, which already pays off on the first race day. Main goal: assessing one’s own abilities correctly. The introduction on the race day itself is brief. It is supposed to start at seven in the morning, with water bottles and bananas provided as provisions.

Pietro, who knows the cars like the back of his hand (after all, there are black-and-white photos of him as a child with these cars), obviously assumes that any semi-talented person can handle a car from 1950. In principle, he is right, but I don’t know when I last sat in such a crate with an open shift gate. The seats feel like the old sofa on my grandmother’s roof; seatbelts, headrests? Not a chance.

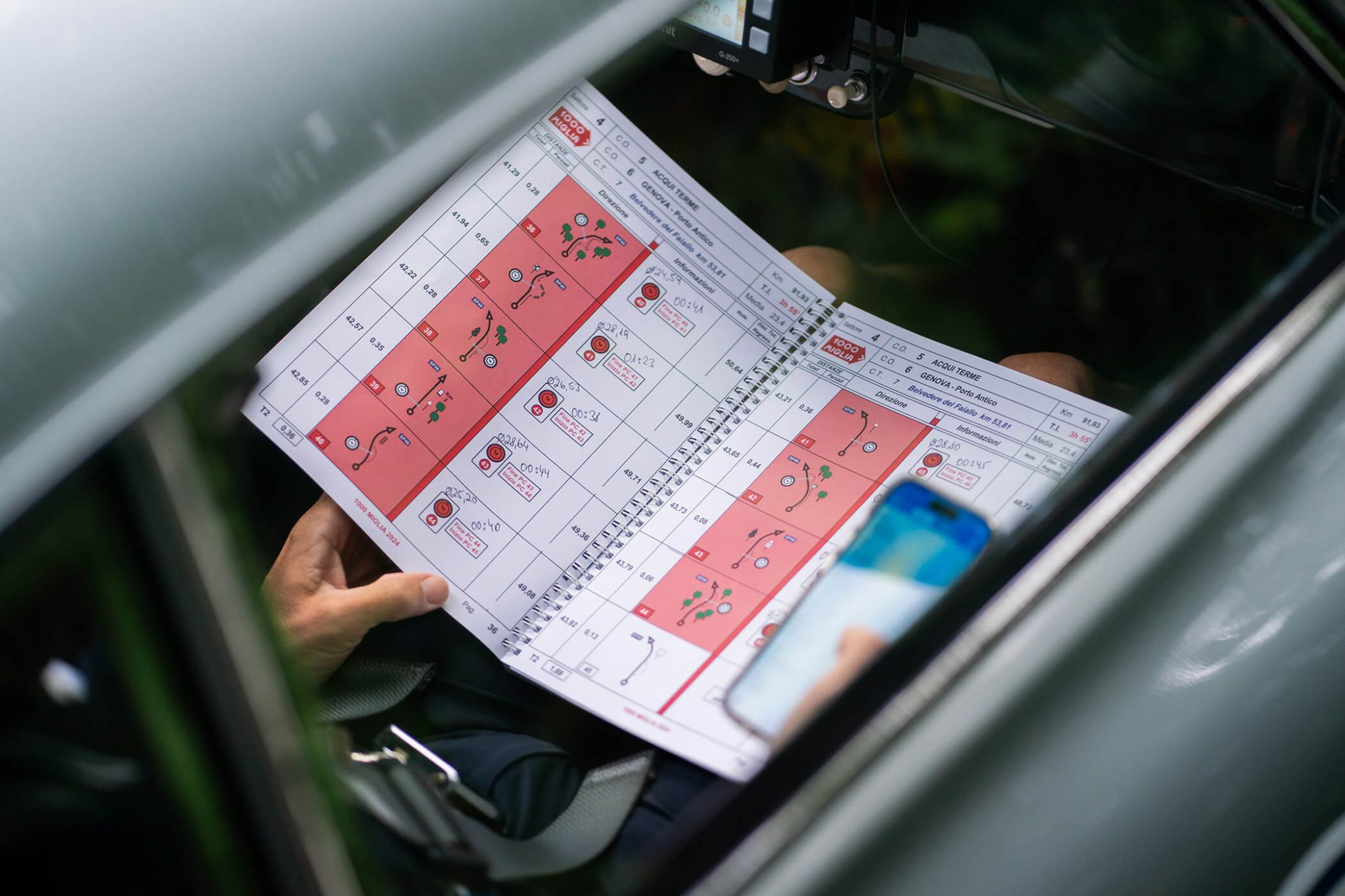

With the delicate, plastic-covered metal steering wheel in hand, it feels like I’ve gotten into a fragile toy car with a frame as thin as a cardboard box. Am I supposed to cover a good 1,000 kilometres in three days with this? I furrow my brow. My assigned co-driver Steven from Worldtempus is also a journalist. When asked who would drive first, he politely declines: not only is he used to English roads and thus the gear shift on the other side, but the fact of a manual gearbox with an open shift gate commands his respect. Mine too. Because an open shift gate means: the gears do not automatically engage, you feel them rather than simply engaging them as usual with the clutch pressed down.

In view of the rain from the previous day, I cautiously ask Pietro again about the functionality of the windshield wipers, which look like they came from a children’s toy store. With a squeak, the two ten-centimeter long, rock-hard rubbers moved slightly upon pressing a button, asynchronously, a process that can hardly be called windshield cleaning. And which of the unlabeled buttons was again the additional engine cooling, which, via a fan reminiscent of a computer fan, directs the engine heat directly into the vehicle’s interior? Super-Pietro had only given me a thumbs up and then disappeared with the accompanying vehicle.

The drive to the starting point in downtown Turin becomes a daring adventure. My co-driver loses track completely after a minute on the Turin city highway, and I try (of course without indicators and without an electric horn) to find a way through the Turin morning traffic.

Steven wants to prepare extensively at the starting line again, but as soon as we get there, we are waved forward by many friendly helpers in safety vests. Straight to the start! I only hear “Go, Go, Go” from the race management, and suddenly we find ourselves on the racetrack lined with spectators on the city’s exit road.

I feel sorry for my co-driver in that moment, who firstly couldn’t go to the toilet like I could, nor really mastered the picture book-thick roadbook. We should get used to the next few days that this race has always been driven with a co-driver since the beginning.

The route from Turin leads over the 670-meter-high Turchino Pass down to Genova, and in the afternoon continues to the Mediterranean seaside resort of Viareggio, at least that’s the plan. The car struggles laboriously up the Strada Provinciale 456, which connects Genoa with Masone and thus the Ligurian port city further along the road with the Piedmontese province of Alessandria. In the meantime, I struggle with the jerky manual transmission and apologise every time I catch a gear, while constantly stirring the gearbox. It cracks and creaks, and I try to take the hairpin turns somewhat elegantly, which isn’t always easy, since of course there is no power steering installed. Multiple times I come to a stop just short of an embankment wall. Steven takes it with British humour, and doesn’t let it show.

Luckily, I had learned the most important lesson in the preliminary video call: brakes, brakes, brakes. After just a few kilometers, my cramped right thigh is in pain because this car naturally only has drum brakes. The warmer they get, the harder I have to step on them. And I mean that literally. The route to Viareggio is only about 380 kilometers long. I’m slowly beginning to guess how early racecar drivers must have felt.

British motorsport journalist Denis Jenkinson described the greatest challenge of this race after the legendary victory as co-driver of Stirling Moss in 1955 as follows:

“When one considers that the race leads over 1,000 miles of ordinary, unprepared Italian roads, the only concession to racing being that all traffic is kept off the roads for the duration of the race and the way through the towns is lined with straw bales, one will understand that the task for a man to learn every curve, every hairpin bend, every incline, every bump, every crest, and every railway crossing is nearly impossible.”

Denis Jenkinson and Stirling Moss, after their participation in the 1955 Mille Miglia

However, there is a small difference: our route is not closed to regular traffic; on the contrary, it is packed. In addition to the more than 420 vintage cars, there are at least as many support and service vehicles, and there are also the vehicles from many parallel events that this major Italian event attracts. Not to mention the countless spectators and would-be participants who constantly overtake you in modern cars. Here, a comparison with Germany is appropriate: can anyone imagine a public car race taking place on the route from Hamburg to Munich and back, in which the police are indeed present the whole time with many motorcycle escorts, but regulated traffic flow is out of the question? I try to concentrate intensely and always keep enough distance, which I had been strongly advised to do.

When we crossed the Turchino Pass in the fog, my co-driver and I were already looking forward to the stop at Genova’s harbour and the detour along the roads of the Riviera di Levante to the south. And naturally, we didn’t notice that our car was slowly but surely breaking down.

During the endless serpentine descent of the valley, it gets warm in the cabin. No, not just because of the summer sun, which is getting stronger and warming the curved metal roof. At first, I suspect the brakes since my leg now feels numb, even though I’m constantly using the engine brake, causing the car to jump like a stubborn mule every time. The heat, initially pleasant after the cool pass, comes from the engine compartment.

Pietro had warned us: watch the radiator temperature! If the thermometer should rise above 90 degrees, it was agreed to turn on the subsequently installed but reliable fan mentioned earlier. Although it blows the warm engine exhaust directly into the interior, Steven and I don’t think much about it.

What we two greenhorns hadn’t considered: the coolant temperature should never go above 100 degrees, even for just a few minutes. How long had the needle been stuck at the 110-degree mark now? Inexperienced as we are, we’re driving with a completely overheated engine onto the completely clogged city highway into Genoa to reach the checkpoint at the harbor.

As biting white smoke rises between my legs, it also becomes clear to Steven that we need to act, but how? We just manage to make it to the highway exit and the turn-off, but a few meters before the destination, participants who have already arrived are nervously jumping around us and shouting loudly: “Shut off the engine or you will burn your car!”

Said and done, but when I pull out the ignition key, absolutely nothing happens. I release the clutch and stall the engine. Together, we jump out of the car, with the smell of burnt oil and rubber in our noses, as it trails a plume of white smoke behind it. Back on our feet, we push the broken-down Fiat to the agreed meeting point with our mechanic team, under the sympathetic looks of the many onlookers at the roadside.

Pietro zooms in with a Maserati and sends us to lunch instead of giving us a lecture. Only now do Steven and I realise that we both smell like berserkers. The smell of gasoline in my nose wouldn’t leave me for days. Anyone who knew urban car traffic in the pre-catalytic converter years knows what I’m talking about: the sometimes kilometre-long line of hundreds of vintage cars has permeated every pore of my body with its smell.

The devastating news arrives a few minutes after the Risotto a la Milanese is served: Pietro informs us matter-of-factly that the head gasket of the Fiat engine has given up the ghost. Thank goodness the cylinder head isn’t warped yet. The gasket will be brought from Milan overnight, everything is organised. However, the race is over for us today. I apologise profusely and promise to do better, but honestly, Steven and I aren’t entirely ungrateful. On the bus shuttle to Viareggio, I immediately fall asleep. A car delivered, this could be good, I think to myself. There is one advantage to the forced break: there is plenty of time to take a closer look at the Mille Miglia watches from Chopard, the real reason for participating here.

As mentioned earlier: since 1988, Chopard has been supporting the Mille Miglia. From this long-standing partnership, an extensive watch collection has emerged over the past 36 years, bearing the name of the legendary long-distance race: Mille Miglia.

After such a long period, it is fair to speak of a classic, especially since this collection has a unique feature that can only be found at Chopard: Since 1988, Chopard has been designing a new Mille Miglia model each year, which in the early years was produced exclusively for the drivers of this famous race.

You read that right: every driver team receives a watch. This is also unique in motorsport history. This year, there are three watches at stake: The so-called Competitor Watch refers to the mentioned watches for the drivers, which each driver team receives at the start, and is included in the entry fee of around 15,000 euros. For those who think this is an excessive amount of money: The package includes, besides the Competitor Watch for each driver team, all accommodations, meals, events before, during, and after the race, along with the roadbooks and of course the overall organisation. Participating in a historic car race has never been cheap, but those who already have their own mechanic team will be able to cover these costs as well.

This year, the Mille Miglia collection essentially comprises two lines: The Classic and Annual Edition GT, available all year round. While the watches from the Classic line are inspired by the classic racing cars of the years 1927 to 1940, the GT line draws its inspiration from the racing cars that participated in the Mille Miglia between 1940 and 1957.

The participant’s watch is visually identical to the Mille Miglia GTS Chrono Limited Italian Edition 2024 Titanium 100 Piece Edition shown here. The only difference: the engraving on the back is naturally different. This model is meant as an homage to the driver’s watch and is only available in Chopard boutiques in Italy this summer.

Chopard Mille Miglia GTS Chrono Limited Italian Edition 2024 Titanium 100 Piece Edition

The third, rather classic model was already presented at the Watches and Wonders in Geneva this spring. The official Mille Miglia Chronograph is called “La Gara”.

On the first race day, I wore the classic Mille Miglia Chronograph with a 40.5-millimeter case made of Chopard’s own Lucent Steel alloy. An alloy with a recycling content of at least 80 percent. Box-shaped glass, the colors of the dial are inspired by the black and white checkered finish flag, the dial carries the designation “La Gara” – the Italian word for “race”. The Lucent Steel case has the quality of surgical steel as well as hypoallergenic properties, ensuring high skin compatibility and a comfortable wearing experience. Lucent Steel is 50 percent harder than conventional steel and is therefore particularly suitable for withstanding the rigors of motorsports through shocks, blows, and scratches.

Bezel, crown, and pushers of the appealing chronograph are also made of Lucent Steel and feature a finish with alternating polished and satin surfaces. The pushers are knurled and visually reminiscent of the ridged metal of our Fiat’s brake pedal. The crown is more distinctly notched, making it easy to grip and operate. The lugs are welded to the case.

The design of the three black subdials, the shape of the hands, and the Arabic numerals are inspired by the characteristic look of a historic automobile dashboard and fit perfectly with the display panel in a historic racing car. The white minute markers and white tachymeter scale contribute to good readability. The dial markings, as well as the hour and minute hands, are also coated with white Grade XI Super-Luminova. The central seconds hand of the chronograph has a red tip, complementing the famous red 1000 Miglia logo, which, of course, appears on the dial of each piece in this collection. Through the sapphire crystal case back, one can view the chronograph movement with automatic winding, certified as a chronometer by the official Swiss chronometer testing institute COSC. The movement with Chopard exclusive finishing is based on the Valjoux 7750 caliber, has a power reserve of 54 hours and costs 10,100 euros.

A brief excursion into the history of the collection: It was only since 1997 that the Mille Miglia watches were no longer reserved solely for racing drivers, but were also offered for sale in limited quantities. The quantity is determined by the year: For example, in 2014, Chopard produced an additional 2014 chronographs with stainless steel cases for general sale, apart from the 410 pieces reserved for race participants. Since it was never planned to let the Scheufele family’s enthusiasm for vintage cars grow into its own watch collection, initially, there weren’t always watches: In 1989 and 1992, exceptionally, a keychain and a pair of cufflinks were added to what would later become a collection.

Over the decades, the Mille Miglia watches have not only served as an intense playground for model studies, but they also document the profound transformation of an industry whose products today are light years away from the state of technology in 1988. This is evident when comparing the first model of the 1988 collection with the current model from 2024: The only thing both watches have in common is that they are both chronographs, with the first Mille Miglia from the late 1980s being a quartz watch, which was contemporary at the time.

The relationship between the Mille Miglia models has always remained visible. The collection owes this to specific features, such as the typical Mille Miglia arrow in red and white, and red elements that are often used in combination with black. The sporty character of the models is in the foreground, even though the models were not always chronographs, as in 2006 and 2015. However, all of them have a tachymeter scale, and the use of luminescent materials is common, since the Mille had a nighttime stage for many years.

The first mechanical Mille Miglia appeared in 1990. At that time, Chopard presented the first rattrapante chronograph made of steel with a mechanical movement. In 1994, the Dunlop Racing strap made of natural rubber was introduced. The typical racing tire profile from the 1960s adorns many models in the collection. Since 2011, it has been fully integrated into the case.

In 1997, two innovations were added to the collection: from then on, Chopard equipped all models with an automatic movement and has been offering Mille Miglia models in limited quantities for sale each year. Since 2000, all automatic chronograph movements used have met the requirements of the Swiss COSC for special accuracy.

Recent design features include the bezel made of blackened aluminum (2012), mushroom-shaped pushers (2013), and the renewed use of the signal color red on the dial (also 2013). But back to the race.

While we spend the evening at an open-air dinner and the driver teams arrive tired but happy, the bad news comes to us the next morning at the start. The Fiat is completely out of the race. But as Pietro smiles while informing us that the green coupe is unfortunately not available, my gaze drifts to the second car, which is parked at the roadside like a sleeping jaguar.

Pietro briefly explains that a driver dropped out and now there is a unique opportunity to drive a genuine participant vehicle from 1952. However, this means my co-pilot Steven and I go separate ways. My new co-pilot is Swiss, named Pierre André, and I can hardly believe my luck as he too prefers reading the roadbook to sitting behind the wheel. Now begins the part of the drive that I will probably never forget for the rest of my life.

Maybe a few remarks about the wine-red, open 1952 Ermini Sport Internazionale. As soon as I start the engine, communication with the co-driver is practically over. The engine roars and growls like a wild beast! When we put on the obligatory racing helmets, we agree on hand signals to guide me. When I try to stow my rain jacket, I realize it ends up on the street because there is no vehicle floor behind the seat for weight reasons, only the asphalt of the road. And what looks like a trunk that could hold about 80 liters fits only fuel: The entire trunk is a fuel tank!

My Swiss copilot and I embark on the journey to the starting point with this little beast, but this time much more relaxed. The car is so loud that in the dawn half of Viareggio probably begins to hate us. We thunder down the coastal road. Anyone next to us at the traffic lights immediately takes phone photos or shouts wildly with gestures. It doesn’t matter to us: only the ticking of the engine can be heard.

For the second leg of the drive, I am wearing the limited edition of the Mille Miglia GTS Chrono, which is basically identical to the driver’s watch but limited to 100 pieces and only available in Italy. The model with a bead-blasted 44-millimeter titanium case is made of Grade 2 titanium. Aesthetically, this timepiece interestingly combines various black and gray tones with a DLC-coated crown and pushers, as well as a matte gray dial with black counters. The strap is made 100% from recycled Seaqual yarn, which is made from recycled plastic waste from the Mediterranean. The black rubber lining is water and sweat resistant, providing a comfortable feel on the wrist. A Swiss chronograph movement based on the Valjoux 7750 calibre with the same exclusive Chopard finish as the Classic model and with chronometer-certified precision runs inside, with a power reserve of 48 hours, as in the classic model based on the Valjoux 7750 caliber. The black tachymeter bezel is made of aluminum. The case back is engraved with a checkered flag, the 1000 Miglia arrow logo, and the inscription “Brescia > Roma > Brescia,” reminding me of the reason for our participation: Where was the starting point again? We find it and off we go!

On the third stage, the route takes us through the Tuscan hinterland, including a drive through Lucca, before returning to Livorno and continuing to Castiglione della Pescaia. As always, it is marked by the eagerly anticipated descent from the mountains to Rome, where we will be welcomed by a parade on the Via Veneto late at night against the backdrop of Roman ruins.

But there are still about 650 kilometers to go. This car is a phenomenon. I never thought I would feel so safe in an open sports car from 1952: Perfect road handling thanks to an extremely low center of gravity, easy to steer thanks to its 600 kilograms weight, and a gearbox that forgives everything.

As we stop for an espresso in a village whose name I have forgotten (and must visit the restrooms out of sheer excitement), we are celebrated by the public as if we have already won the Mille several times. That’s not quite true, but Pietro had told me the history of this car the evening before. It participated in the Mille Miglia and the Targa Florio in 1952, achieving 1st place in its class at the latter. In 1953, it entered the Mille Miglia and the Coppa d’Oro delle Dolomiti, among other important races in the early ’50s.

Only four cars exist in total, of which only two are still running today. The Florentine designer behind the name initially used Fiat chassis and engines, but the Italians soon refined their constructions and developed their own engines, so the car registrations eventually only bore the word “Ermini,” without the “Fiat” addition, while retaining the official chassis numbers. The Florentine car manufacturer used its own advanced numbering system for its engines. The torpedo-shaped car complied with the new regulations of the International Sports Law, which required the direct attachment of the fenders to the bodywork – hence the name Ermini Sport Internazionale. In the same year, with the new engine, Motto from Turin built two more cars, this time with covered wheels as required by the new regulation.

Our chassis 055352 is the car of Aldo Terigi, who participated in the Mille Miglia in 1952 with Pugi but did not finish the race. Terigi instead won his class at the Targa Florio and came second at the Coppa d’Oro delle Dolomiti. In 1953, Aldo Terigi won his class at the Coppa della Consuma and the Coppa Balestrero. The car also participated in the Mille Miglia of 1953 with Bernardeschi, but without success. The car raced in several competitions and was purchased by Scuderia Centro Sud in 1956. I’m quite glad that the restored car runs with a Fiat replacement engine to preserve the original one. It was dismantled and is carefully stored. This way, I can avoid causing another major engine failure.

Our route takes us through Lucca and Livorno, and we reach Castiglione della Pescaia in the bright midday sun. Cheered by hundreds of fans on the roadside, we open our only umbrella upon entering the city to avoid being completely scorched in the summer sun. And since we have learned from mistakes, we gladly turn off the roaring engine in the traffic jams at city entrances, much to the dismay of the spectators. Our lunch break is brief; we don’t want to miss the sunset in Rome and still have 450 kilometers ahead of us.

I cover a long stretch of highway at about 130 kilometers per hour, and the engine sound is so loud that I still feel it as a vibration in my head days later, even after flying back. This speed also reminds me of two other aspects of the race: an accident at such speeds would not only mean the end of the rare car but also abruptly end our lives, of that Pierre and I have no doubt. He had politely reminded me at lunch to adhere to the speed limits. However, a completely different story sticks in my mind, one I can’t comprehend after experiencing the Mille Miglia myself.

The British racing driver Stirling Moss famously won the Mille Miglia in 1955, two years after our Ermini last participated. Moss, along with his co-driver, the aforementioned motorsport journalist Denis Jenkinson, covered the entire route in an astonishing 10 hours 7 minutes and 48 seconds, with an average speed of 157.651 km/h. According to Google Maps, this is simply not achievable on highways with a modern car. But here we are talking about country roads in 1955. The lead that Moss managed to extend over his competitors by the finish was enormous. He distanced his teammate Juan Manuel Fangio, who was already a two-time Formula 1 World Champion at that point, by 32 minutes. Imagine such a thing happening today to a Formula 1 World Champion. The third-placed Ferrari factory driver Umberto Maglioli was already three-quarters of an hour behind. I highly recommend everyone read Jenkinson’s experience report, which can be found online, in its entirety: (https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/june-1955/14/moss-mille-miglia/) For me, it is probably the most impressive motorsport story of all time. Jenkinson is said to have had nightmares about this 1600-kilometer ride for the rest of his life.

While I try to imagine how Stirling Moss and Jenkins fly past meadows and fields with the speedometer needle at its limit, we arrive in Grosseto in the late afternoon and finally reach the Lazio region, where we thunder down to the shore of Lake Bolsena and finally head towards the “Giro di boa” (Italian for turning point) in Rome at sunset.

I can’t say what moved me more: being escorted to the city center of the eternal city by the police as the son of a Latin and history teacher? Or the evening drive around the Colosseum and other sights? At some point, there’s information overload at the Mille Miglia. It can’t get any better.

Completely exhausted, we finally reach Rome, after having received a new battery from Pietro, thankfully, during a fuel stop in the middle of nowhere. After all, being on the city highway in the dark in Rome without an alternator is pretty bad. After inhaling the gasoline fumes of the Ferraris in front of us for hours, we reach the finish ramp and are announced to the crowds on the roadside with a microphone. We shake hands with people we don’t know from the car. I feel as if I am already in Brescia and not just halfway through in Rome. During the subsequent police-escorted city tour, my co-pilot and I miss the exit and use Google Maps to find our way back to the city center, where the car finally comes to a stop next to the famous restaurant and nightclub Jacky O.

After 12 hours at the wheel, sunburned, reeking of gasoline, I gratefully fall into the arms of the mechanic team that includes Super-Pietro, who nonchalantly mentions that the third headlight is now dangling from its wire in front of the radiator grille. He says this relatively casually, given that, when asked by numerous other participants if this wonder of an automobile was immediately for sale, he simply replied: Starting at 700,000 euros, you might be able to talk about it, only to wave them off immediately: the Ermini embodies too much history for him personally.

For me too now, I will never forget the ride down the Apennines. With trembling hands and a buzzing in my head that I would feel for days later – aside from the dislocated cervical spine, as I found out at the doctor’s the following week – the curtain closes behind me on the way to the restaurant. I decide during my evening prayers to only judge things that I have truly experienced myself from now on and raise an ice-cold Peroni to Stirling Moss and his co-driver, who so uniquely summarized the experience of participating in this race that I would like to share it here:

“It was indeed a unique experience, the greatest experience in the (…) years I have been interested in motorsport, an experience that surpassed my wildest dreams, with a result that I still can hardly believe now. After previous Mille Miglias, I have said: The one who wins the Mille Miglia is a driver, and the car he uses is a sports car. I say it again now with the certainty that this time I know what I am talking about and writing.”

Nothing more needs to be added to that. Apart from thanking Karl-Friedrich Scheufele for making this ride possible. He deserves double respect: 37 years of sponsorship and no tiredness: although he could almost be my father, of course he drives the Mille hard all the way to the finish line in Brescia. Just a professional.