With the Oyster Perpetual Deepsea Challenge, Rolex once again revives the idea of the past: the watch as a true tool.

In order to understand this article as a watch enthusiast or a collector: forget the Louis Vuitton stereotype. Forget the queues going round the corner and burly bouncers at the door. Forget the logo. We are here to understand the real Louis Vuitton. The French maison. The company founded in Paris in 1854, by an ambitious man from impoverished rural France, who would make trunks for Napoleon III’s family, and whose designs would go on to seduce Coco Chanel, Audrey Hepburn, Jackie Kennedy. Through the ages, this company has calculatedly grown and adapted to the times almost impeccably.

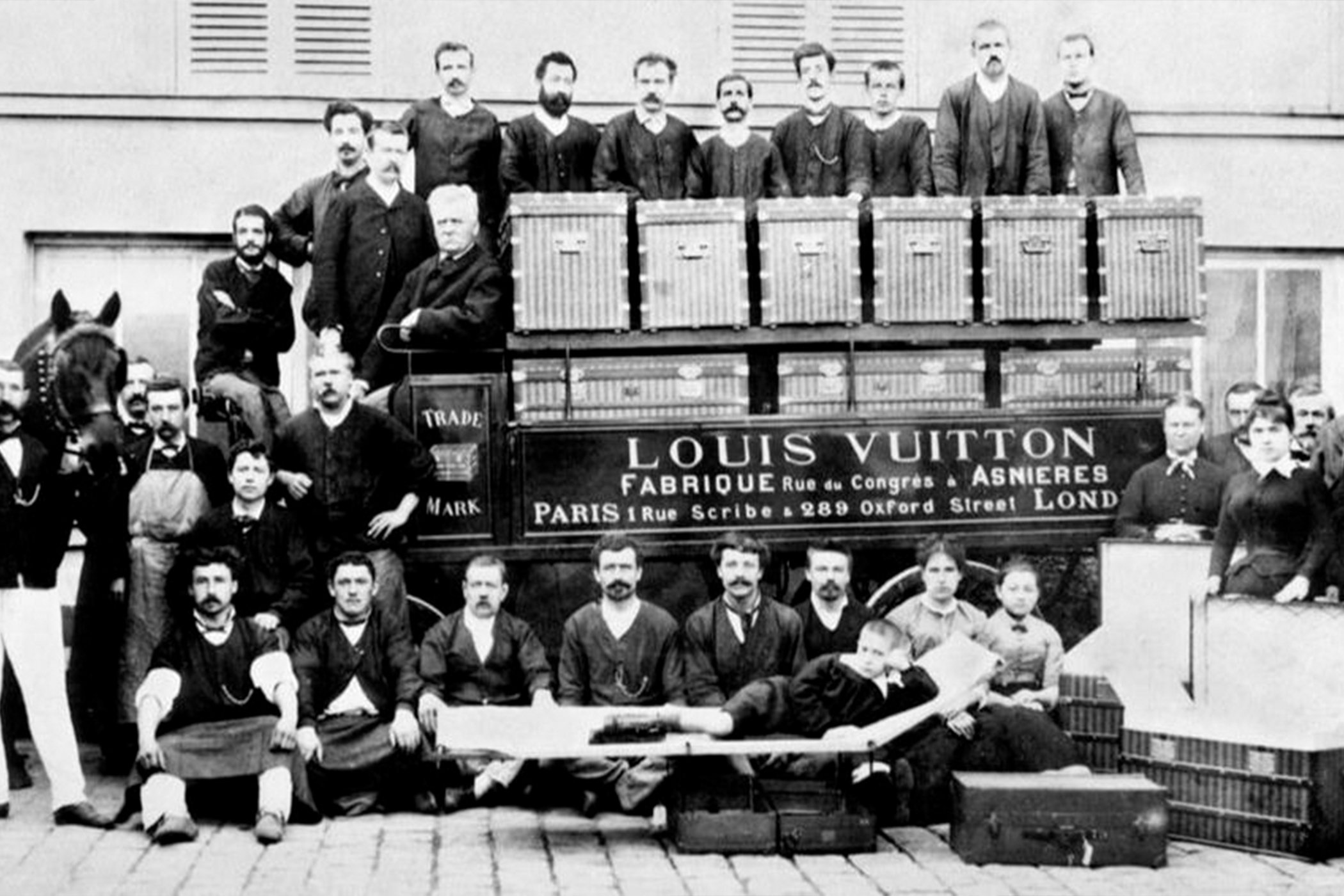

The Vuitton family with staff in Asnières,

France 1888

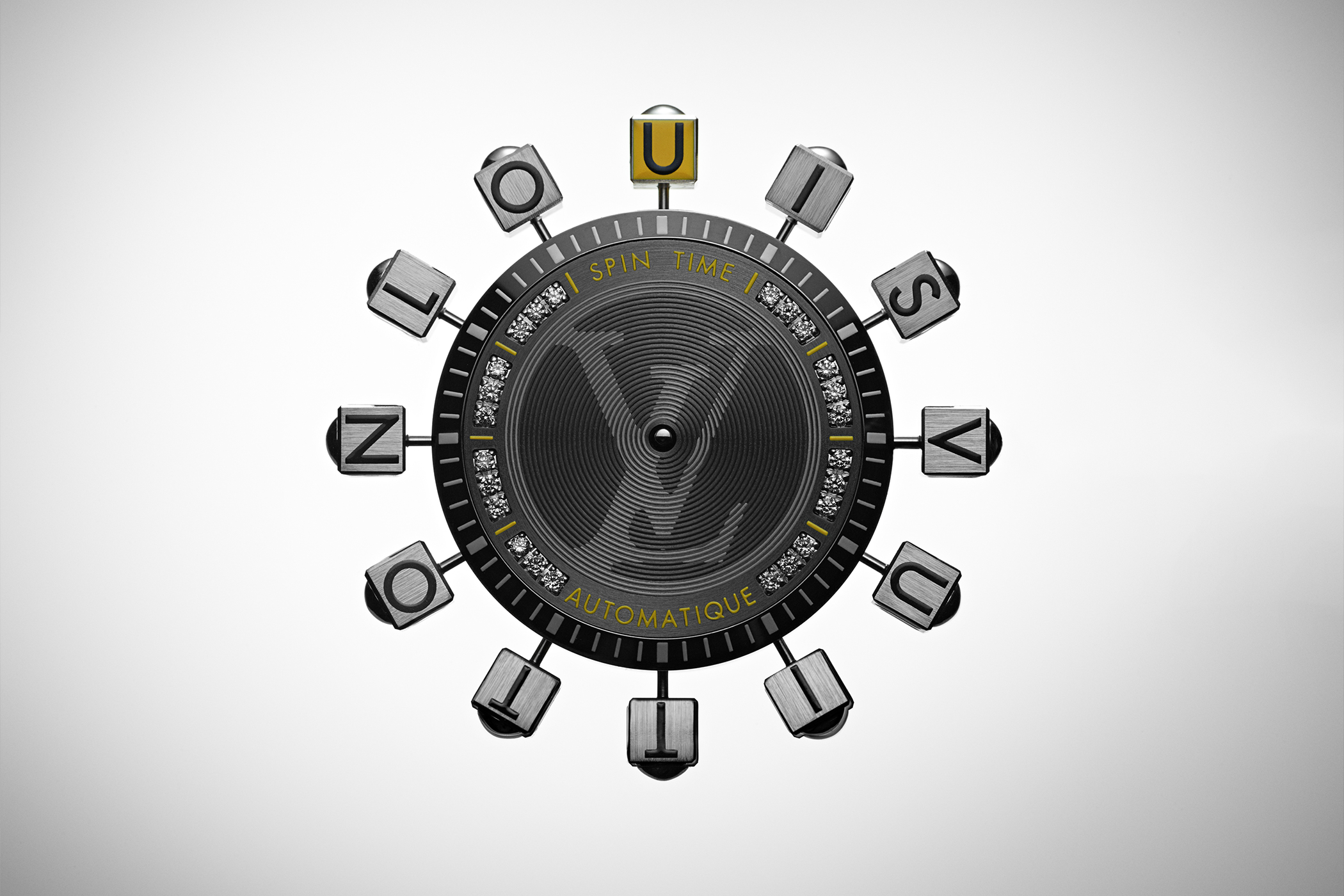

In 2002, however, the very core of the brand was altered as it brought an ambitious new vision to life: creating its own Swiss mechanical watch. This would lead, eventually, to the creation of the Fabrique du Temps in 2010, which would become the perfect example of how to crack the impossible code: establishing a fashion brand as a reputable player in the Swiss watch industry, without casting off its high-fashion cape.

La Fabrique Du Temps – Louis Vuitton

It’s a big risk. Other leading international fashion houses have tried to create their own legitimate Swiss timepieces and failed. A successful example, of course, is Montblanc, with its acquisition of the Minerva manufacture back in 2007. Suddenly armed with a marketable history, alongside all the knowledge and expertise that comes with it, the leather goods and writing instrument manufacture steadily grew into a highly reputable watchmaker, with numerous Montblanc pieces already revered by collectors.

The second manufacture based in Le Locle, where quality management takes place since 1996

Louis Vuitton, however, took a different path. Upon the launch of its first mechanical watch, it had almost no history to its name. Prior to that point, Louis Vuitton’s sporadic release of timepieces, such as travel clocks and the inspirational Gae Aulenti’s quartz-powered Monterey I in 1988, were few and far between. Nevertheless, as that model indicates, the avant-garde approach to watchmaking was in the air from the very beginning.

1988 – Louis Vuitton LV1, Ref. N03000.

Drawn by Gae Aulenti, exclusively developed by IWC.

Louis Vuitton was born in 1821, starting life in a small village in the Jura mountains. Even then, the Jura was known as a historic area of watchmaking, particularly the towns of Neuchatel, La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle. Neuchatel, for example, was already home to the revered master of watchmaking, Daniel Jeanrichard, by the late 1600s.

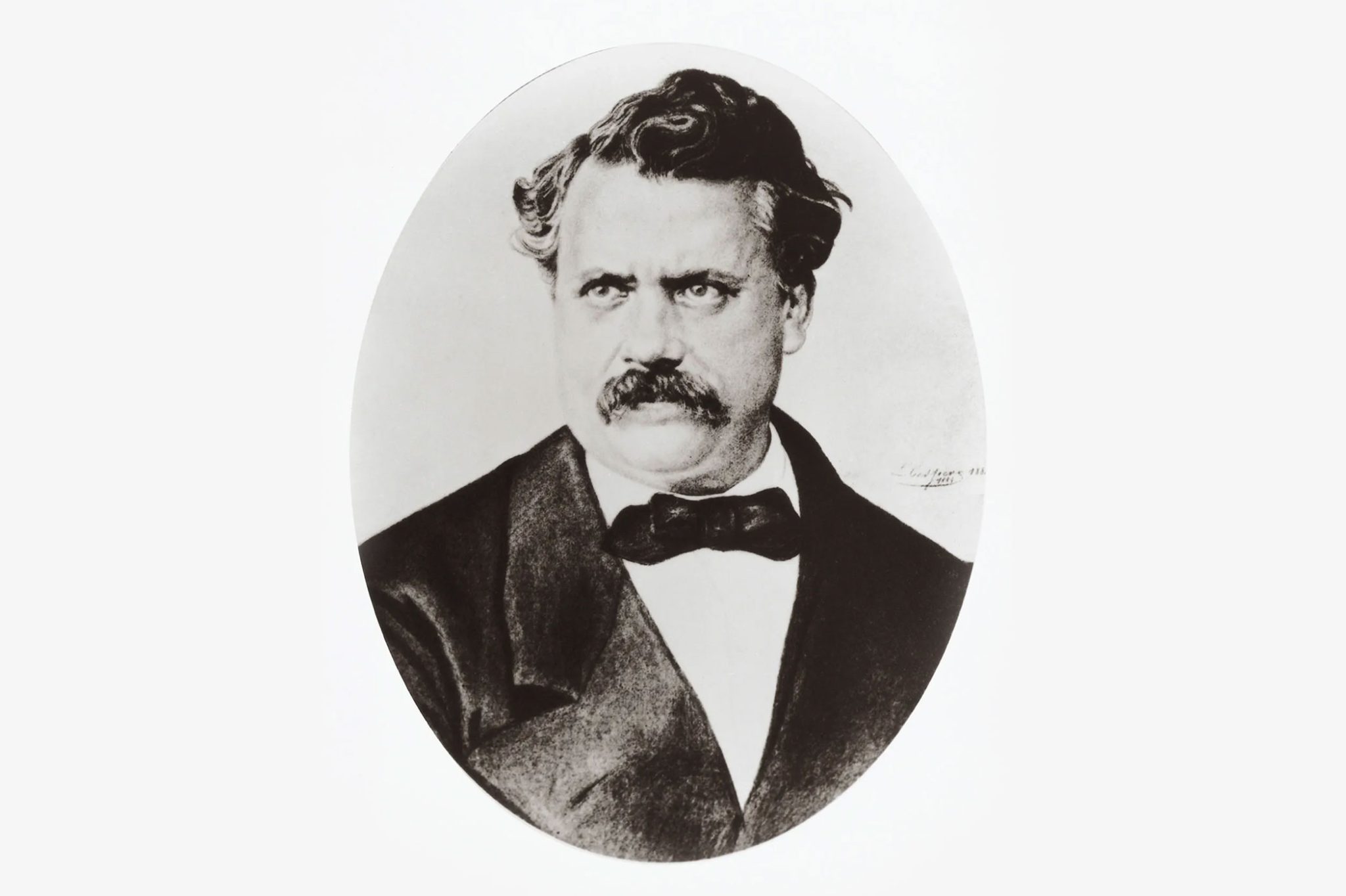

A portrait of Louis Vuitton (1821-1892)

Louis Vuitton, however, grew up in the French village of Anchay on the opposite side of the Jura, about 170 kilometres away from this ever-growing nucleus of Swiss watchmaking. Many inhabitants of his hometown travelled no further than Thoirette, a market town six miles down the road – an ironic birthplace for the man who would found the most famous travel product company in history.

Jura Mountains, Switzerland

Photo by Léonard Cotte

In other words, Anchay was not a place where people had much vision, experience, or chance of progress. The young working-class Louis probably did not attend school. Rather, he will have worked dawn until dusk helping his hatmaker parents, who also owned a small farm. The only attire – fashion would be the wrong word – he might have seen are the hats made by his mother, and perhaps uniforms made for the military nearby. France was still recovering from the bloody and divisive Napoleonic wars only two decades prior. Industry was pretty much non-existent. Farming was a lifeline, with the economy relying largely on the cultivation of wine.

The Battle of Fère-Champenoise (1814)

Near Fère-Champenoise, France

By the age of ten, Louis Vuitton was known as a stubborn child with little interest in cultivating his family’s land. His age, however, was an achievement in itself, given that infant mortality stood at almost 50 percent. His mother died that year – this was no great surprise, as the life expectancy of French women was only 30 years. At the age of 13, Louis Vuitton resolved to escape his dreary existence. As legend has it, he decided to leave in order to flee from his evil stepmother, who could give Cinderella’s a run for her money.

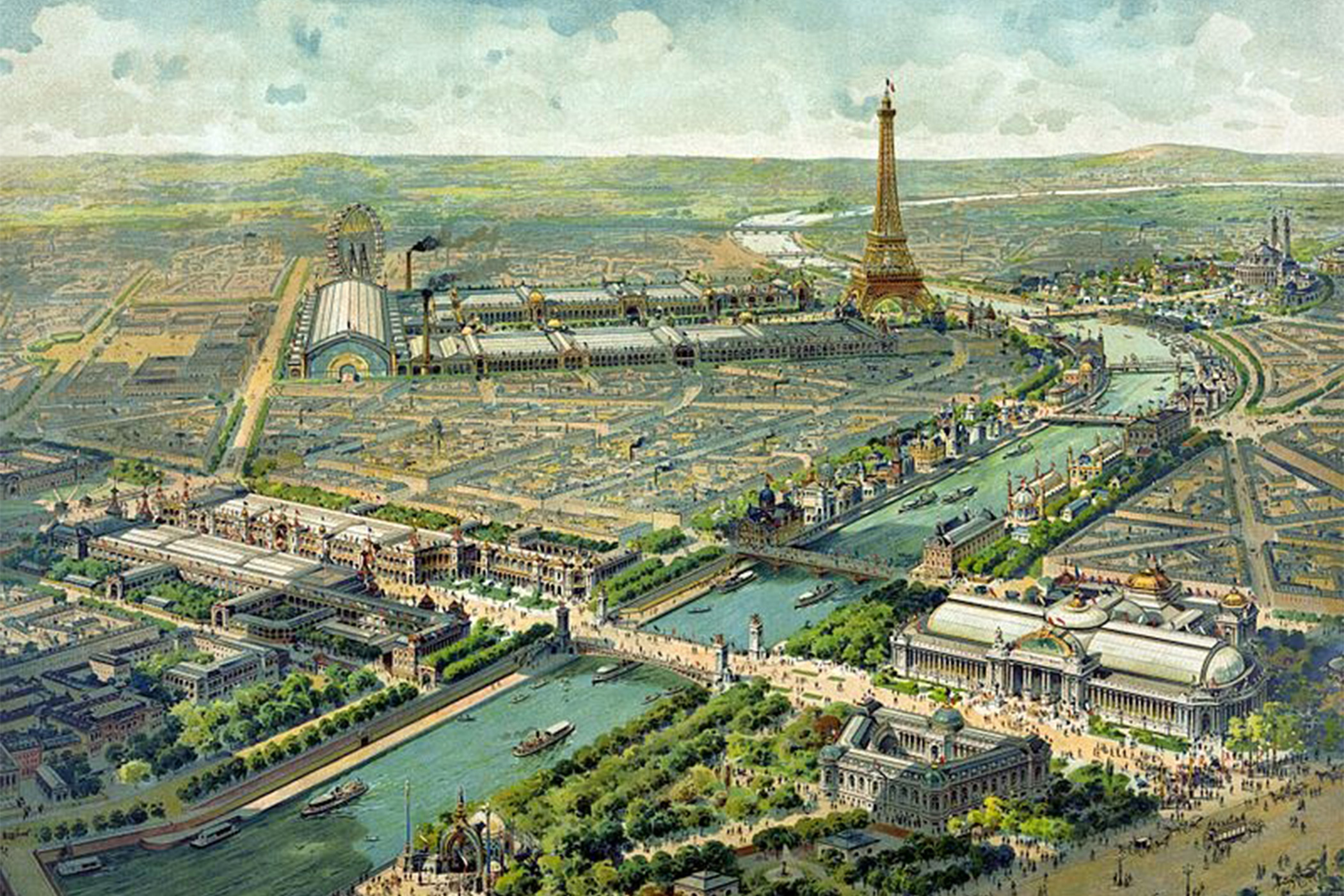

Paris (1900)

Louis Vuitton left Anchay in 1835. It would take him no less than two years, with countless odd jobs to pay the way, for him to reach Paris by foot. Upon his arrival in 1837, he was met with the very dawn of the French industrial revolution: intense wealth, devastating poverty, dirt, and disease: but also the chance to succeed. He started as an apprentice for a Parisian box-maker, a respected craft, before founding his own company in 1854. His luggage soon gained admiration, catching the attention of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife. Becoming the Empress’ personal box-maker gave Louis Vuitton access to the crème de le crème of Parisian society. Thus, the once impoverished farmhand rose to the dizzying heights of craftsman to France’s elite.

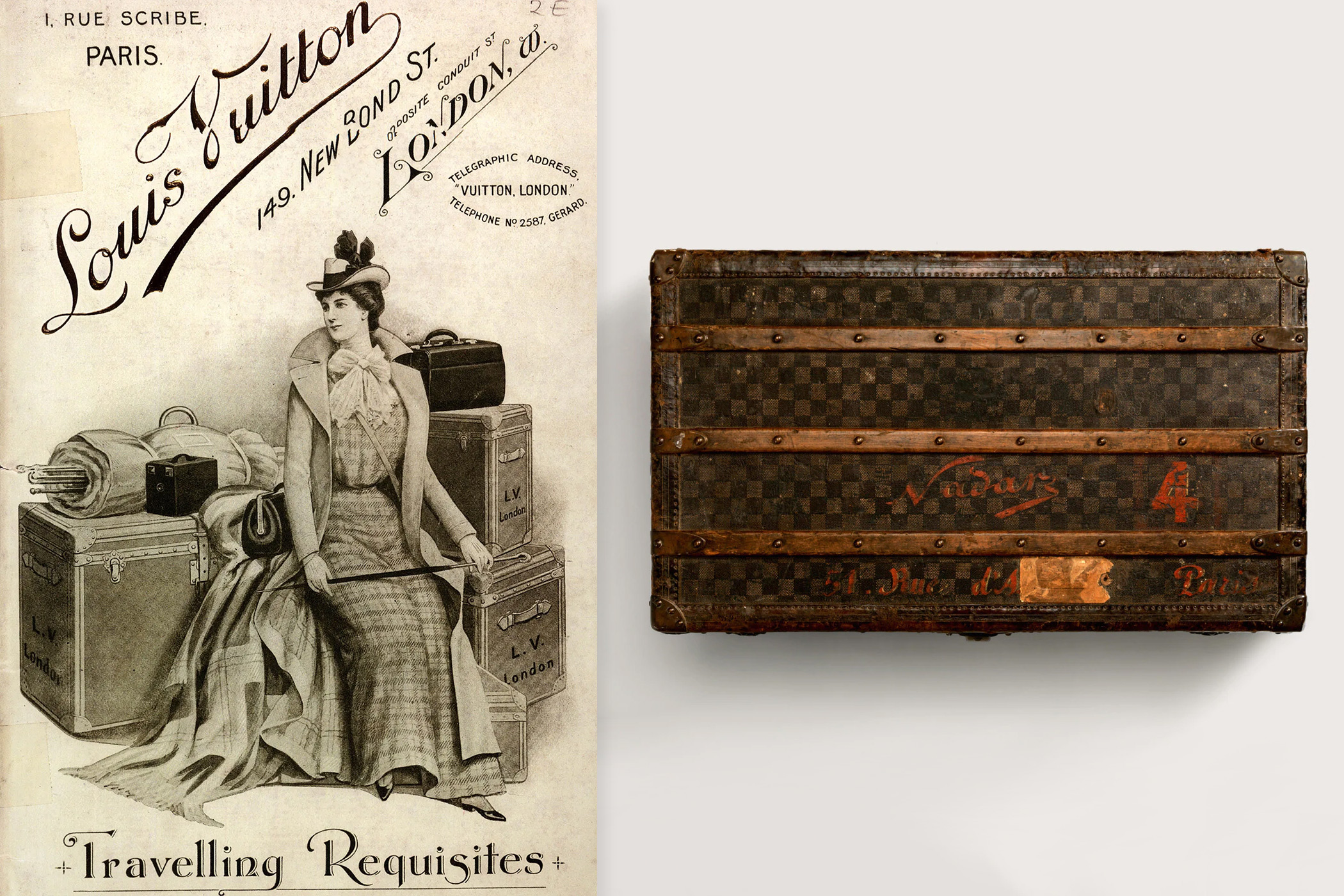

Credit: Little Book of Louis Vuitton,

The Story of the Iconic Fashion House by Karen Homer

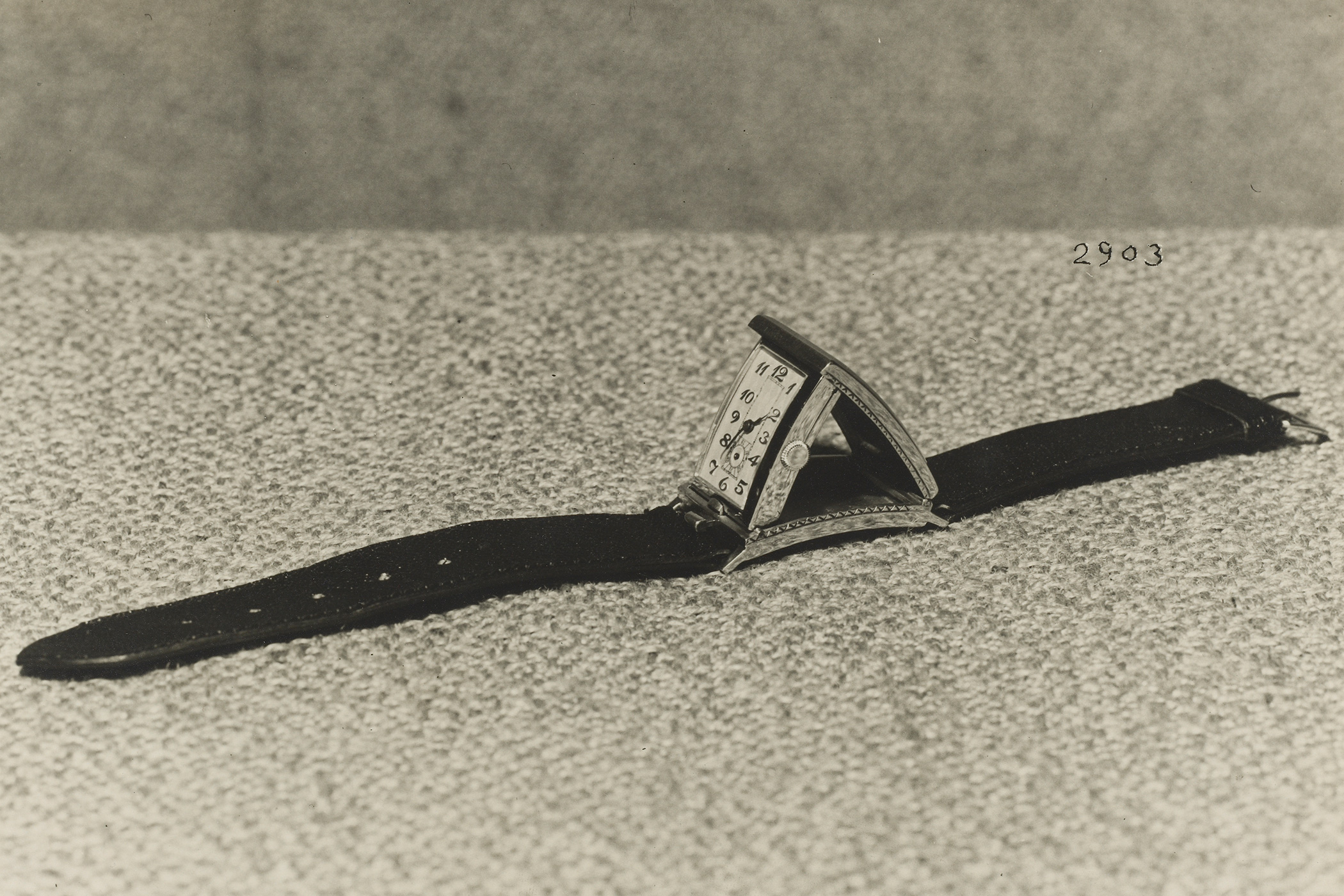

As far as haute horlogerie is concerned, however, we must fast-forward 168 years. In 2002, Louis Vuitton shocked the watch world with the introduction of its very own timepiece. Shocked, of course, because this tremendously famous fashion house had barely dabbled in watchmaking before that point. With the exception of producing travel clocks in the 1920s and 30s, it didn’t appear to be part of its DNA.

Vintage travel clocks from Louis Vuitton

The only notable exception would be the Louis Vuitton Monterey watches, which have now become sought-after collector’s pieces in their own right. The Monterey II Alarm Travel Watch, created by IWC Schaffhausen for the fashion house, had travel, style, and innovation in its DNA. One of the first ever ceramic watches, it offered a second time zone and elegant pointer date. Of course, the quartz timepiece came with a Louis Vuitton leather strap. Likewise, the 1988 LV1, also designed by Gae Aulenti and created by IWC, included ten features set around a single axis, including a retrograde date, moonphase, GMT and 24 Time zones.

2002 marked the genesis of the Louis Vuitton high watchmaking we know today. The Louis Vuitton Tambour watch, Ref. Q11310, was housed in a highly distinctive case without a bezel. This first Tambour was a travel-appropriate GMT with an automatic movement housed in a 39.5 mm steel case. The in-house movement used the ETA 2893 for its base. It was accompanied by four other introductory pieces: three hour and minute quartz watches for women (in 28 mm, 34 mm, and 39.5 mm) and a 39.5 mm chronograph for men. Each featured a brown or red sun-brushed dial and fully polished case.

In the late 90s and 2000s, a number of fashion brands began to dabble in the field of mechanical watches. The stylish new watches weren’t just pieces for horology connoisseurs; these were created for those interested in fashion, too. Chanel, for example, had already launched its ceramic J12 by 1999. One reason for the boom, as profits from mechanical watch production surpassed that of its quartz counterparts for the first time in three decades, was men’s renewed curiosity for the mechanisms within traditional timepieces. This factor of gender would also prove integral to the beginnings of Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking story.

For Louis Vuitton, the incentive behind what would become the brand’s most iconic watch was indeed to create something specifically for men. At the company’s headquarters in Paris, Louis Vuitton’s then-Jewellery and Watch Director, Jean-Louis Roblin, resolved to launch a timepiece that would capture the interest of potential male customers, balancing out the overwhelmingly female audience seduced by the company’s fine bags and scarves. Louis Vuitton collaborated with Parisian agency BBDC to create what is now the Tambour: an (initially) masculine watch with a strong sense of ‘Louis Vuitton’ in its DNA. This DNA was also decided from the start: it should also be a luxurious, timeless yet innovative watch to endure through the generations: not a fashion piece to be enjoyed one day and forgotten the next.

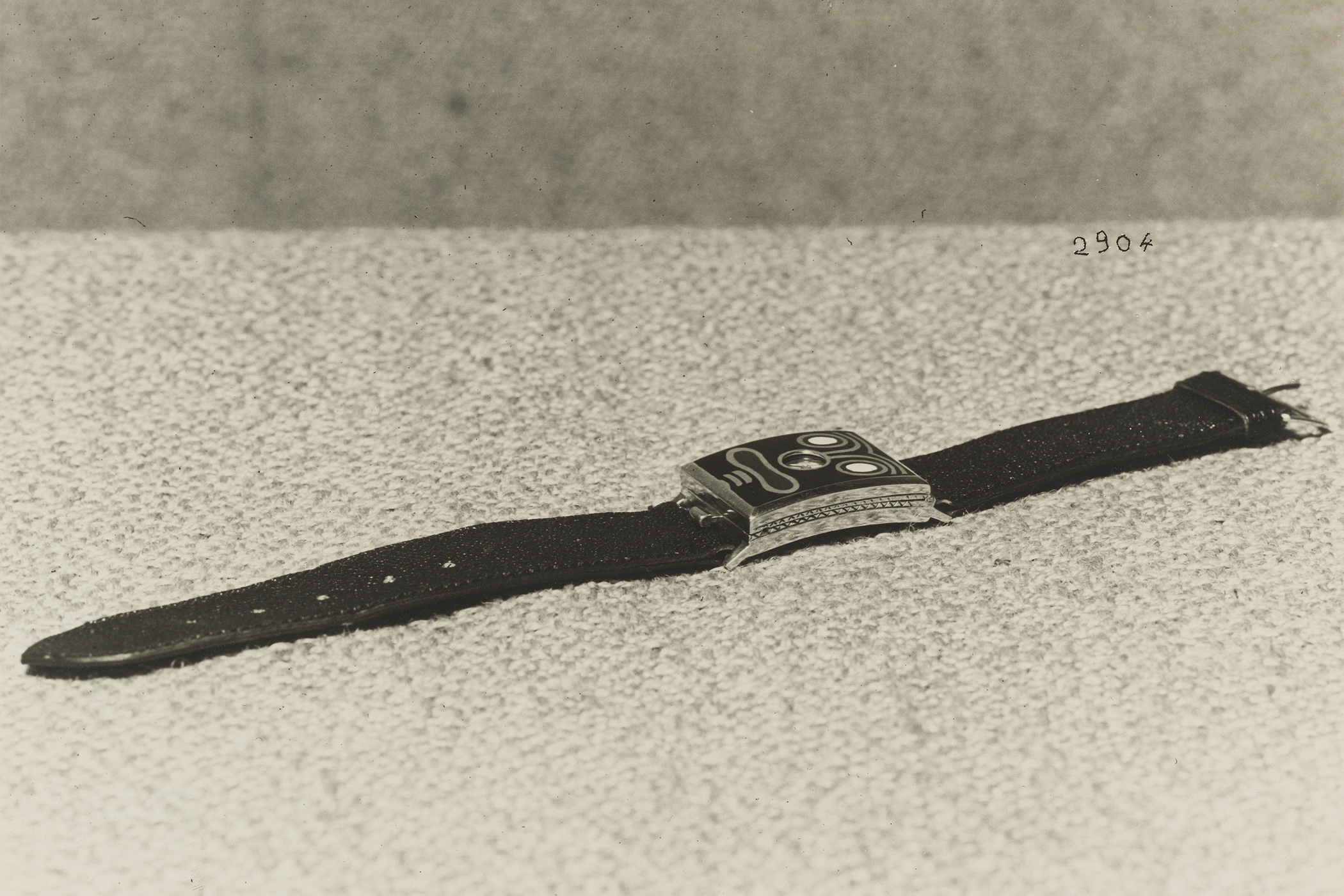

Unlike any case seen in the industry before, the eponymous watch model was shaped like a drum – more specifically, the Japanese taiko drum. The watch’s launch neatly coincided with the opening of the maison’s flagship store in Tokyo. Taking just under two years, designers came up with the idea of a drum-shaped case by comparing a watch indicating time to a drum creating a rhythm, noting the links between music, rhythm in time and rhythm in music. Furthermore, of course, there’s a ‘drum’ component in watch movements. Meanwhile, the Tambour case lugs nod to the company’s travel roots, imitating the same shape as the handles on Louis Vuitton trunks. In doing so, the watch evokes the same idea of reliability, style and strength as its luggage has been offering since 1854.

Last but not least, engraved round the case and aligned to each hour marker on the dial, are the 12 letters: L O U I S V U I T T O N. Accomplishing a high level of finishing on this polished case, which gives the appearance of being sculpted out of a single block of steel, is a challenge. Producing such a high quality, full-polished case is no easy feat.

Today, there are four pillars that make up the Tambour case’s core DNA. As well as the classic case first seen in the original model, three others are at the forefront. One is the Tambour Slim; as the name suggests, it features a slimmer case that suits well to female wrists. Then there’s the Tambour Moon, launched for the 15th anniversary of the Tambour, which is a ‘concave’ expression of the original Tambour. Interestingly, it’s this case shape that is also used for Louis Vuitton’s smart watches. Finally, the fourth core Tambour case shape is the Tambour Curve, first appearing two years ago. Watches in Tambour Curve cases are used solely for high watchmaking at Louis Vuitton. The most futuristic of the Tambour cases, it has a modern silhouette while staying true to the blueprint of the iconic case and lugs.

In 2008, the Louis Vuitton company planted its watchmaking roots in Switzerland, inaugurating the Ateliers Louis Vuitton in La Chaux-de-Fonds. A good 90% percent of components assembled there are Swiss-made, from movement parts to cases and hands. Movements at this atelier principally use ETA bases, as well as help from the likes of Zenith – its sister company within the LVMH group – and we’ll certainly get to its El Primero chronograph calibre later.

From 2009 onwards, Hamdi Chatti steered Louis Vuitton as Head of Jewellery and Watchmaking, remaining in the position for just short of a decade. Having gathered experience in micro-technology and engineering, followed by an MA in Horology at the University of Neuchatel and stints at Harry Winston and Montblanc, he was highly focused in his goals from the start. His aim was always to entice horology fanatics with not only style and strong design codes, but also with technology. What should define the watches, he resolved, should also integrate travel into their DNA – and this is evident in numerous Louis Vuitton models today, despite Chatti no longer being with the company.

Having met with the man himself in his third year at Louis Vuitton back in 2011, we at Swisswatches can attest that Chatti’s modesty and innovative strength played a pivotal role in the initial phase of watchmaking at Louis Vuitton. Chatti propelled the company’s horology through his awareness of the fact that, while Louis Vuitton had a big name, its watchmaking department at that time did not – despite its numerous successes. While at the helm, Chatti therefore instilled the importance of going the extra mile and challenging other manufactures in the industry through ever-higher levels of watchmaking.

In 2009, the company came up with a whole new way to read the time. The launch was a surprise to many watch journalists of the decade, who were quick to assume Louis Vuitton would not be launching anything horologically ground-breaking. They were wrong.

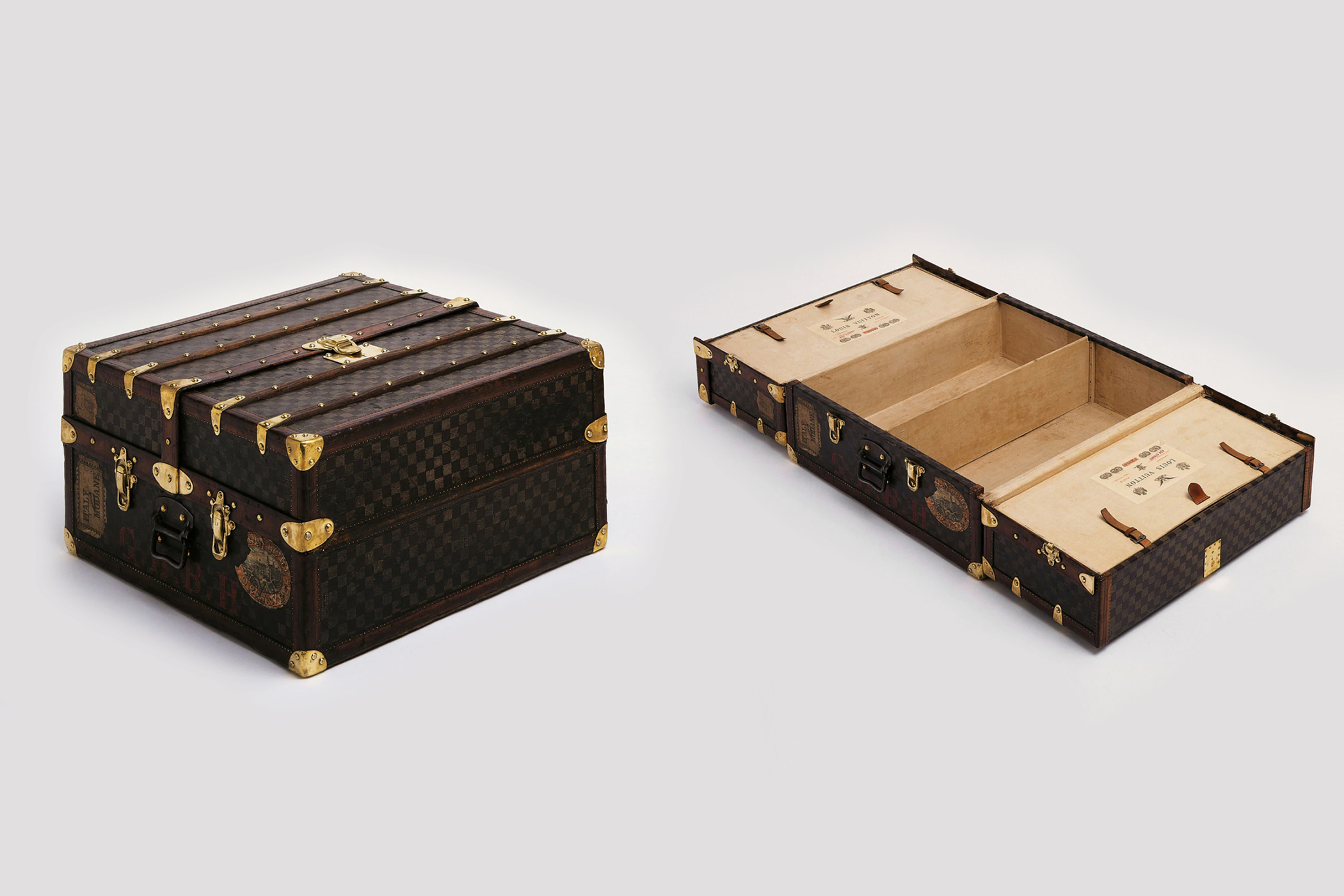

Escale Spin Time Meteorite Dial Pink Gold

The patented Tambour Spin Time movement translates a jumping hours system into rotating cubes. Usually, a jumping hours watch will feature an aperture on the dial, indicating the hour. On the innovative Spin Time, however, playfully decorated cube hour markers spin around to show the time.

Once again, not only innovation but also travel played an important role in the watch: its designer, Michel Navas, was inspired at an airport as he watched the mechanical list spinning its flaps to display the latest destinations and departures. The first calibre inside the Spin Time watch was crowned the LV8. While the original Spin Time was fairly minimalistic, models such as the Regatta chronograph edition introduced new colours, themes, and complications, from GMTs to World Timers.

Another such colourful piece was the Tambour eVolution Spin Time. The Tambour eVolution models are globe-trotting pieces which, by rule of thumb, house either a GMT or GMT-chronograph calibre alongside a day/night indicator. The watches, unlike the ‘classical’ Tambour, if you will, are overtly masculine in their design. Compared to the typical curvaceous Tambour case, the eVolution cases have a highly contemporary silhouette with taut lines and a high-tech feel. With jet-black colour schemes that employ light-weight black MMC features, these edgy watches are most fast-paced and ergonomic than other Tambour models, with an easy-grip ridged crown.

Tambour eVolution Spin Time GMT

As mentioned above, in 2011, Louis Vuitton took on a full watch manufacture: La Fabrique du Temps, which now produces 30,000 Swiss timepieces per year. Comparatively speaking, this production size is still extremely exclusive compared to the brand’s global size and fashion sales – as well as compared to other manufactures in the watch industry. Even Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet, for example, produce around double this number of watches per annum.

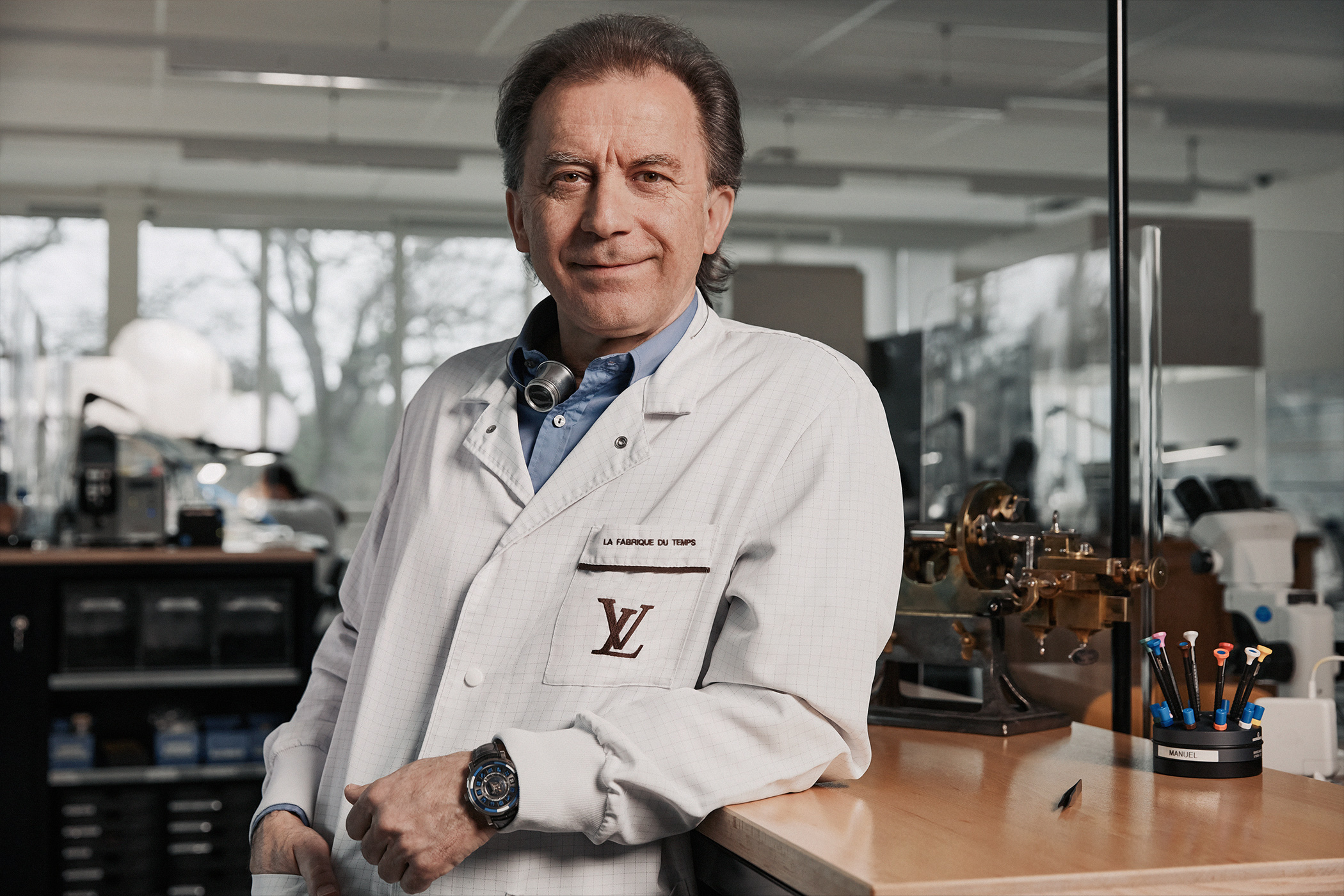

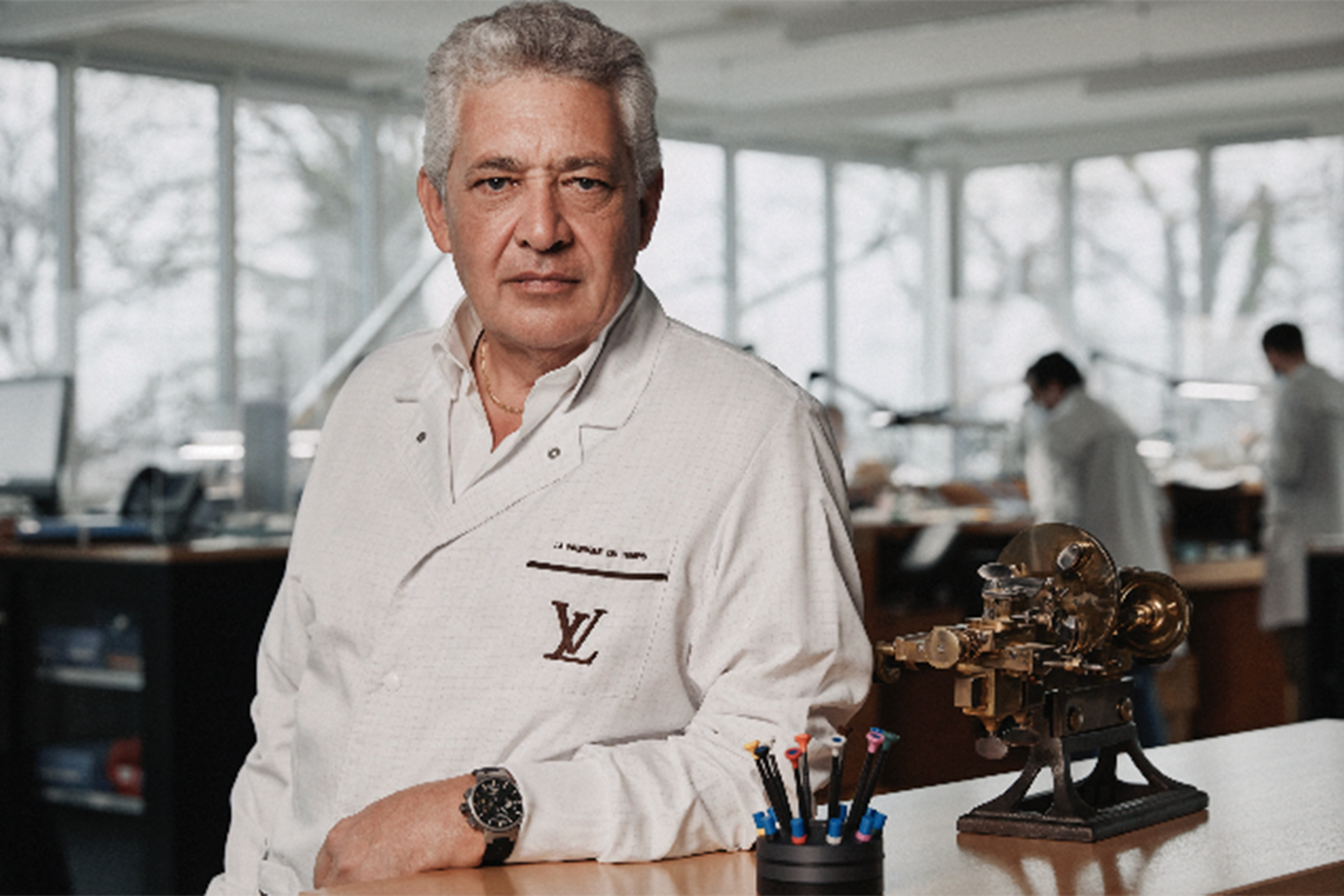

While the maison’s atelier had formerly been in the Swiss watchmaking town of La-Chaux-de-Fonds, its bucolic new location, situated 144 miles away in the municipality of Meyrin, brought the horology house much closer to Geneva. While first and foremost home to CERN, the world-famous European particle physics research centre, the area also has an extremely strong watchmaking background. Le Fabrique du Temps’ neighbours include the likes of Roger Dubuis, Chopard, Le Ateliers Horlogers de Van Cleef & Arpels and Richemont’s Campus Genevoise de la Haute Horlogerie, to name but a few. Here you will find the workplace of Louis Vuitton’s engineers, designers, and other experts, headed by master watchmakers Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini. The latter pair agreed to join on the condition they would work towards obtaining the Geneva Seal at Louis Vuitton – we’ll have to read on to find out if this dream came true.

Some watch manufactures, for example Piaget, use several different locations to produce their watches. Others such as Jaeger-LeCoultre, and indeed Louis Vuitton, unite all production under one single roof. La Fabrique du Temps unites producers of movements with designers and watchmakers alike, constituting a workforce of about one hundred people in total. This allows the manufacture to work as swiftly and efficiently as possible.

Louis Vuitton’s more ‘high fashion’ watches, by the way, use quartz or external movements. This allows all focus to remain on haute horlogerie. Alongside the two master watchmakers responsible for high-end pieces, Enrico Barbasini and Michel Navas have a whole team behind them who work on the development and production of new movements. In total, Navas (who we can see as the technical guy) and Barbasini (the creative dreamer) have conceived no less than twenty successful movements, many with highly intricate complications, over the last twenty years.

Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini

Credit: Louis Vuitton

When it comes to building a mechanical watch at Louis Vuitton, an ‘A to Z’ structure is used. One sole watchmaker is responsible for the whole process on the watch, from the assembling components, to finishing by hand, to testing the function of the completed watch.

As mentioned, creating stunning dials is of great importance at La Fabrique du Temps. In the same year as the creation of the workshop, Louis Vuitton brought Lèman Cadran on board, integrating the renowned dial workshop into the manufacture. The Lèman Cadran workshop masters a range of techniques, from diamond setting and enamel dials to miniature hand painting.

Time to return to Zenith’s aforementioned El Primero: only a few months after the launch of the original Tambour, the first chronograph Tambour appeared, housing the LV277. The movement used the El Primero by Zenith as its muse: the famous first automatic calibre with its 5 Hz (36,000 vph) frequency – allowing it to measure 1/10th of a second. But fear not, fans of Louis Vuitton: the brand would later create its own ground-breaking movement.

In 2013, Louis Vuitton made its own mark in the Swiss watchmaking industry with the creation of its own in-house specialised chronograph movement, housed in the nautical Tambour Twin Chrono. This monopusher chronograph, celebrating the America’s Cup and the company-founded Louis Vuitton Cup, was designed specifically for yacht racing. The twin chronograph movement LV 175 thus displays two chronograph subdial counters tracking each yacht’s time, while a third shows the time difference between the two racing boats. In order to achieve this precise measurement, the specialised calibre integrates a three-layer column wheel.

With a highly legible dial, a four-stroke pusher and two winding crowns, the manufacture also placed great emphasis on usability, creating a simultaneously simple-functioning yet complicated, ground-breaking new mechanism. Creating this great feat of horology took 437 components – 40 of which were specifically invented to create the Twin Chrono LV 175 calibre. Only two years after taking over Le Fabrique du Temps, Michael Navas and his team proved to be well and truly on track. The Twin Chrono movement is an exceptional example of what a powerhouse such as Louis Vuitton can achieve with the right people behind them.

Here comes another example. In 2016, Louis Vuitton reached every young Swiss watch manufacture’s dream: acquiring the Poinçon de Genève. This coveted seal, in existence since 1886, essentially signifies a horology house’s ability to work to the absolute highest standards of the industry, from finishing and decoration to a movement’s precision. To this day, it’s pretty much the most coveted accolade a watch can receive. For Louis Vuitton’s Le Fabrique du Temps, it firmly signalled to the world that their watches were to be taken seriously once and for all. So far, the maison has three Geneva seal movements to its name: the aforementioned Voyager Flying Tourbillon, followed bythe Tambour Moon Flying Tourbillon, and the Tambour Curve in 2020. Several of these, observant readers will note, were tourbillons; Louis Vuitton has been producing tourbillon watches for a long time, with the first already produced in 2004 (although this used a mechanism from La Joux-Perret).

Louis Vuitton’s own in-house (Poinçon de Genève) Calibre LV97

The first Louis Vuitton watch to receive the Poinçon de Genève was the Voyager Flying Tourbillon in 2016, featuring a vertically mounted mechanism in order to expose the intricacy of the mechanics at play. Furthermore, it introduced a brand-new case, entirely different to the Tambour. This new case had unusually shaped rounded bezel and airy architecture, with swathes of space between the movement situated around the edges, while seemingly floating in the centre. At 12 o’clock, the time was displayed on a transparent disc, and the aethereal flying tourbillon lies at 6 o’clock. It is a stunningly unique, highly impressive watch – it quickly becomes apparent that this is a watch worthy of bearing the Poinçon de Genève, which is proudly engraved at 3 o’clock.

The second watch to receive the prestigious hallmark was the Tambour Moon Flying Tourbillon in 2017. The Tambour Moon Flying Tourbillon marked not only the manufacture’s second Poinçon de Genève timepiece, but also the introduction of a novel concave Tambour case. More streamlined than the original Tambour case, it measured a wider diameter of 42.5 mm yet a shorter height of 9.65 mm. Furthermore, the watch also introduced a new quick-release system for the straps. This complicated watch, powered by the LV97, integrated a one-minute flying tourbillon, but in no ordinary form. Rather, it came in the shape of the Louis Vuitton’s signature monogram flower, visible across the maison’s product range, from bags to bracelets. This adds a high fashion touch to a high horology watch: a rare sight indeed. The movement (LV97) also has an innovative yet aesthetic design. The fully open-worked movement presents the bridges and base plate as concentric circles, exposing the single barrel at 12 o’clock – a stylish and educating delight to behold for fans of watchmaking.

Tambour Moon Flying Tourbillon “Poinçon de Genève”

Last but not least (for now), the Tambour Curve, unveiled in 2020, is the most recent watch to receive the Poinçon de Genève. The Tambour Curve brought a sportier, more ‘masculine’ watch to the table, with lugs that smoothly integrate into the strap. Let’s appreciate the relevance of this, given the ultimate aim of the Tambour’s very creation was initially to create something masculine. At the same time, the first Tambour Curve signalled that the manufacture was equipped to venture into the field of innovative materials as well as ever-complex movements. The other aim of the seriously sizeable watch, with its case diameter of 46 mm, was to integrate only high-end movements (made easier by the amount of space the case provides).

Tambour Curve GMT Flying Tourbillon

Louis Vuitton’s watch manufacture used titanium and CarboStratum for the watch, with the latter being a material specially conceived for the company, consisting of over 100 layers of carbon. Powering this first ultra-light model was the LV108, which integrates a flying tourbillon in a futuristic titanium cage. The movement, made of platinum, was covered with a black coating. The Tambour Curve, with its Geneva seal manual-winding movement, would later become even more well-known thanks to the inclusion of its dual time function in 2021.

The first interesting point to note about the Escale WorldTime is that the model from 2014 and Time Zone vary greatly – far more than one might realise upon seeing both pieces at first glance. They are a good indication of Le Fabrique du Temps’ continuing journey to try and test what works for the manufacture’s workforce, its production of watches, Louis Vuitton’s clients and the prices that result from these factors. Secondly, it could be argued that this watch encapsulates the Louis Vuitton and Fabrique du Temps relationship more succinctly than any other watch: boldness, colour, style, innovation, and of course travel packed into a single piece. The WorldTime dials’ unusual symbols take inspiration from vintage trunk monograms, when owners of Louis Vuitton trunks would have their own personal symbol designed to mark out their cases.

Escale Time Zone

The first Escale WorldTime to emerge from the maison was created in 2014. A million miles away from the definitive Tambour design, the watch was housed in a slim new ‘bezel-less’ case, with a diameter of 41 mm and fairly slim height of 9.75 mm. The size, while obviously looking somewhat broad on slimmer wrists, was a good decision for a watch whose dial should be on showcased as much as possible. After all, this focus of white-gold timepiece is undoubtedly the dial, painstakingly hand-painted in 38 colours and fired by an artisan. Creating one dial alone takes 50 hours.

Escale WorldTime

The World Time complication was conceived by Louis Cottier in the early to mid 1900s, offering the time in 24 zones simultaneously. Louis Vuitton’s Escale WorldTime indicates the time in no less than 24 time zones, while operating via a crown rather than through pushers as is the norm. It’s a watch with no hands and no pushers. Rather, the calibre LV 106 (created specially for the watch) employs a yellow arrow at 12 o’clock, to which one can line up their home city, before setting the local time using the concentric black and white hour and minute discs. These contrast nicely – and impressively clearly once you get the hang of it – with the colourful city markers sitting on the outer circles.

Upon the release of its Time Zone sibling, Louis Vuitton would shift from this artisanal approach of painted to transfer-printed dials, saving hours of work and consequently drastically reducing the price of the watch. In this sense, the maison enabled a haute horlogerie timepiece to become significantly more accessible to a range of customers. Unlike the World Timer, the Time Zone does use hands, as opposed to a fixed indicator, to show the (local) time. A minute hands rotates around the dial via a central axis, while the triangle indicating hours, placed on a disc, appears to float its way around the dial. Both the Escale Time Zone and Escale WorldTime offer something special to fans of horology by making reading the time(s) not simply an action, but rather a meaningful process that requires thought and attention from the wearer.

One of Louis Vuitton’s best-performing watches of all time is the Tambour Street Diver. It was introduced fairly recently, in celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the Grand Prix de l’Horlogerie de Genève. There, the 44 mm timepiece with a black sunray dial, powered by an ETA 2895 automatic movement and water-resistant to 100 m, was awarded the Diver’s Watch Prize. As the name suggests, the unconventional-looking watch combines practicality with flair, coming in highly contrasting bright colours on the rotating inner bezel, hands, and indices.

Tambour Street Diver Skyline Blue,

Winner of the 2021 GPHG Diver’s prize

This Tambour case is not simply steel, but rather combines polished and sandblasted surfaces with PVD treatment for a high-end finish. Despite its recent inception, the line has grown fast. Men are likely to favour versions such as the everyday Skyline or Pacific White, which come with a rubber strap. These are, interestingly, overtly branded, with the words LOUIS VUITTON circling around the wrist. In some ways, this, combined with the relatively simple ETA movement and water-resistance to 100 m, makes the Street Diver a piece that is ultimately for those who enjoy the design or the brand, as opposed to horology aficionados looking for something special. In any case, this has become one of the maison’s top-selling watch models within a very short amount of time.

The Gold Lagoon and Black Blaze models also deserve a mention. Contrasting to the aforementioned models, the watch is less obviously branded, with the words LOUIS VUITTON barely readable due to the letters matching the strap colour. The watch rather catches the eye with its use of rose-gold on the PVD-treated steel case, creating a very contemporary yet smart aesthetic. While the Black Blaze is housed in the typical 44 mm x 12.8 case, the more feminine Gold Lagoon comes in a very slightly smaller, slimmer case measuring 39.5 x 11.8 mm.

Despite only being launched last year, the Tambour Carpe Diem has swiftly become one of the most powerful symbols of high watchmaking at Louis Vuitton. Housed in a 46.8 mm rose-gold Tambour case, it features both a highly intricate dial and watchmaking techniques, resulting in a number of patents. This includes a jacquemart mechanism incorporating four animations (including a snake that indicates the time), jumping hours, minute repeater, and power reserve indicator.

La Fabrique du Temps’ LV525 manual-winding calibre also features decoration by Swiss watch engraver Dick Steenman, while the miniature painting and enamel work on the dial is the work of Chaux-Le-Fonds-born Anita Porchet, who is revered as one of the world’s best enamellers. The Carpe Diem marked an important moment in Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking history, winning the ‘Audacity Prize’ at the Grand Prix de l’Horlogerie de Genève last year (2021).

The Tambour has come a long way since 2002, celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. Louis Vuitton celebrated the milestone with a new Tambour watch, limited to a mere 200 pieces and paying tribute to the original model. The 41.5 mm diameter case engraves the twelve letters of the company, ‘Louis Vuitton’, above the numerals and hour-markers, just like the first Tambour Automatique GMT exactly twenty years ago. Using Louis Vuitton’s signature colour, the Tambour Twenty features a brown dial with sunburst finishing. The three subdials and the angled flange are also brown. Silver-coloured hour numerals at 12, 2, 4, 6 and 8 o’clock, as well as silver-coloured baton-shaped hour markers, make the dial easy to read and leave plenty of space for the subdials.

Tambour Twenty – Limited to 200 pieces

A long yellow central chronograph seconds hand adorns the brown dial – a nod to the yellow thread used in leather stitching in the past. The yellow hands at 3 and 6 o’clock indicate the elapsed chronograph time up to 30 minutes and 12 hours respectively. Furthermore, an inscription in yellow, reading ‘TWENTY’, curves across the lower half. The date window, with a black background and white numerals, lies between 4 and 5 o’clock.

Meanwhile, the rotor of the Tambour Twenty is made of 22-carat rose gold, driving the automatic LV 227 movement, using Zenith’s El Primero high-frequency movement as its base. The automatic movement of the Tambour Twenty beats at an impressive frequency of 5 Hz/36,000 vibrations per hour and offers a robust power reserve of 50 hours. It is accurate to within a tenth of a second. Of course, the limited edition comes in a luxurious Louis Vuitton watch box, which surely carries its own price tag ranking in the thousands.

What we have in this limited edition is a combination, then, celebrating this rare hybrid of fashion and horological heritage. Watchmaking at Louis Vuitton is a constant balancing act. Each watch design is carefully composed, thoughtfully measured, to appeal to a real range of individuals. There’s those who might be a fan of the global brand, opting for a contemporary Street Diver with a boldly branded strap. Others who appreciate the Sonderweg, if you will, that the Tambour has taken, from designs deeply entrenched in the company’s DNA to integrating innovative mechanisms that pay tribute to the joy of travel. The vast and varying repertoire comprising Louis Vuitton’s watch collections is an unforeseen – and perhaps still underappreciated – triumph for the maison.

That said, Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking branch is ever more appreciated, with connoisseurs recognising that the company has well and truly bridged the gap between high fashion and horological heaven. Louis Vuitton’s watchmaking journey proves that time is, indeed, everything. After all, its own manufacture is literally named ‘The manufacture of time’.

While watchmakers at Louis Vuitton have rightly pointed out that ‘merit has nothing to do with the number of years’, there’s no doubt that customers and desires do change over time – what would be the fun of the industry if they didn’t? The younger generation today enjoys physical, branded investments. Decades ago, people looked at TAG Heuer differently to how people regard the fast-paced brand today. People mocked Richard Mille watches, thinking the design was simply too far-fetched. It will be interesting to observe where Louis Vuitton’s watches, many housed in the extraordinary Tambour, situate themselves in this generational web of overlaps and change.

This is something many collectors will be considering as Louis Vuitton’s haute horlogerie and everyday mechanical watches continue to pick up pace. From our point of view, there are a couple of key talking points. From the maison’s side of things, it is important to keep prices reasonable – especially when it comes to the simpler models housing adapted or ETA movements. At the same time, keeping costs down should not equate to over-producing models in large numbers. This is vital if Louis Vuitton are to keep customers content, with a high quality yet (relatively) obtainable luxury product.

Tambour Street Diver

Credit: Louis Vuitton

From a collector’s perspective, we should consider the future of the Tambour. There’s no denying it is an unusual looking watch – yet one only has to look at other distinctive yet enduring cases such as Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso or Cartier’s Crash to know this need not be a problem. Some will nevertheless wonder if investing in, for example, an anniversary Tambour Twenty is a risky game? The answer is: to be a collector, you need to make a bold move now – not in ten years’ time when prices may skyrocket. Again, timing is everything; we are only just entering the third generation of watchmaking at Louis Vuitton. From its inimitable tourbillons to its first World Time from 2014, this manufacture has already passed an astounding number of milestones. It’s time to decide if you want to jump aboard and see where the horological Louis Vuitton journey takes us next.

Mason, F. (2015) Vuitton: A Biography of Louis Vuitton. Golgotha Press.

Reybaud, F. (2022) Louis Vuitton: Tambour. 1st edn. Thames & Hudson.