The ICE St. Moritz, a melting pot of refinement, power and prestige, sees classic cars demonstrate their horsepower upon a frozen lake.

While it is an extreme privilege to have been inside pretty much every Swiss horology house, at some point, a picture automatically forms in one’s mind as to what to expect when visiting yet another manufacture of mechanical watches.

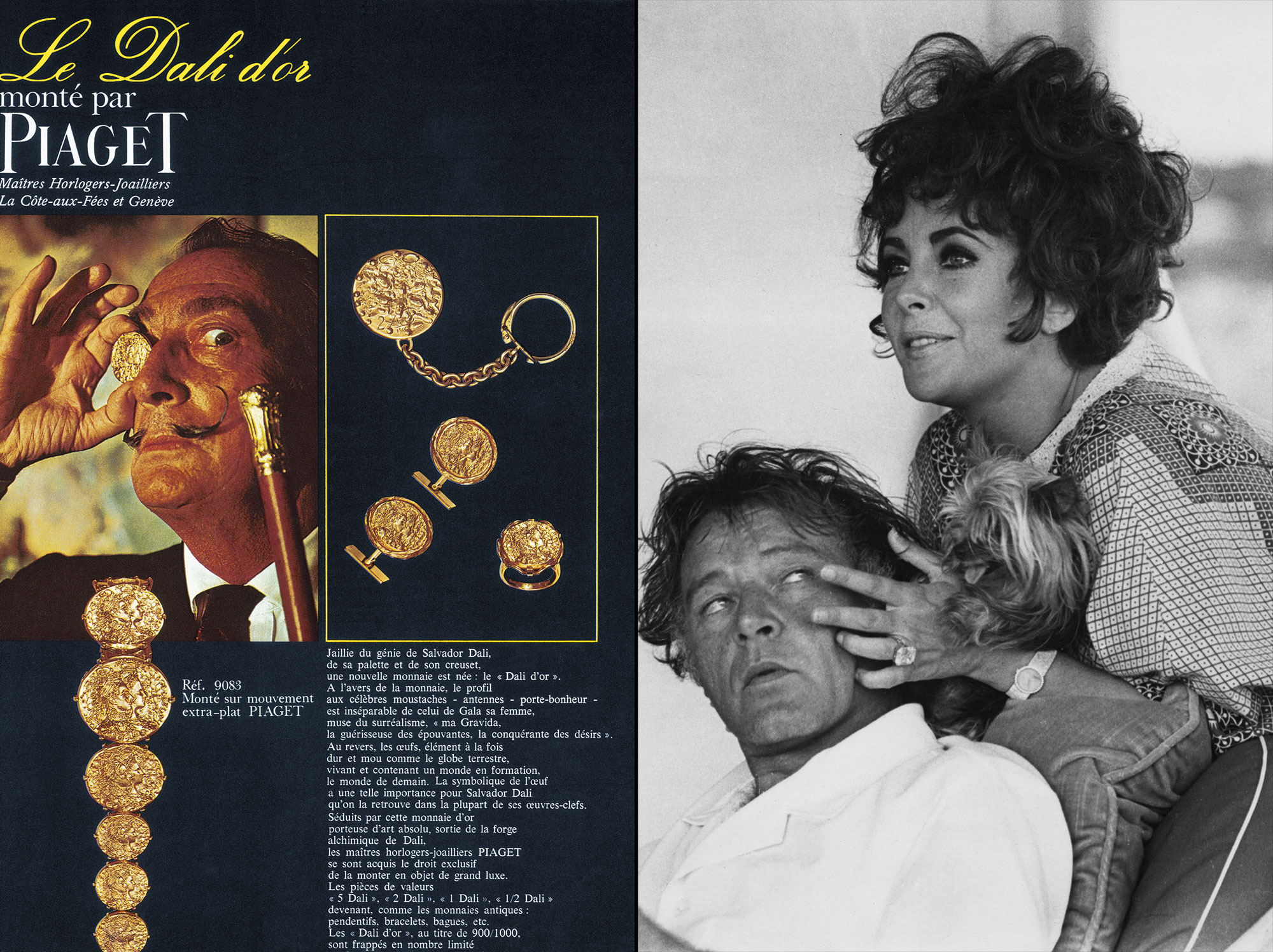

What attracted me most to visiting the Piaget factory in Geneva was my totally fragmented image of the brand, of which I – and I assume many readers feel the same way – essentially knew a few buzzwords. As the ‘Master of Ultra-thin’, Piaget can boast a number of watch world records, but at the same time, alongside these so-called Altiplano models (named after a desert-like plateau in Peru), there are equally elaborate and crazy jewellery watches. Then, there are a number of famous personalities who were all somehow connected to Piaget: Andy Warhol, Salvador Dali, Jackie Kennedy or Elizabeth Taylor, to name but a few. Even a rose is named after this company: the Yves Piaget rose. So how do artists, First Ladies, Hollywood legends and botanists fit together to make the whole picture? For those who are just as curious about this question: welcome to this somewhat different manufacture story from Swisswatches.

One thing is certain: most real watchmakers have next to nothing to do with the glossy marketing brochures you get from big-name companies in a watch boutique. Watch production is ultimately an industry, and it is often the image of machinery and the smell of lubricating oil that lingers when you leave these buildings. And yet, it is not uncommon to blink in astonishment upon arriving at a manufacture, because you are not standing in an industrial area, but rather in front of a mountain, a romantic little forest, or a meadow where cows or, as in this case, sheep are grazing.

So much for the images in my head. I had expected all of this from Piaget – as it turns out, this story contains both industrial machines and meadows. But there is definitely one thing I did not anticipate seeing: its own gold smelter. The fact that it exists purely for recycling purposes is all the more impressive. It says a lot about a watch manufacture that is, in fact, much more than a watch manufacture. It is a jewellery and watchmaker of the highest order and in many ways, historically as well as currently, a pioneer of modern watchmaking.

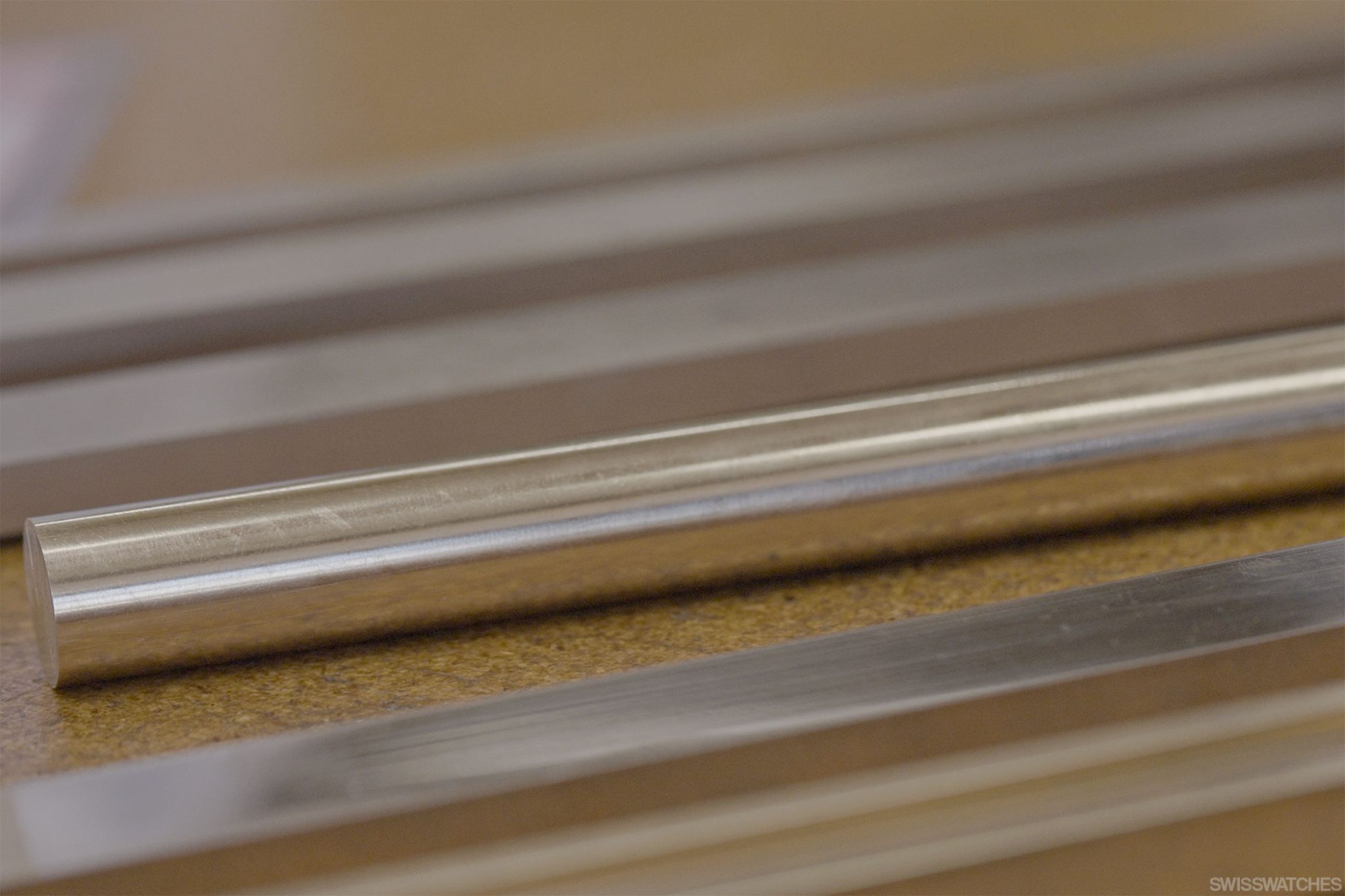

Who has seen live how an eight-kilo bar of gold is cast? I certainly haven’t, and it made a lasting impression on me, especially when you realise: this is waste. Once a week, a gold caster comes to Piaget in Geneva’s luxury industrial district of Plan-Les-Ouates, to melt about eight kilos of precious metal worth about 429,459 euros (as of 8 November, 2022) into a single bar, which, security permitting, you can feel the weight of in your hands just a few minutes after melting. This is the amount of dust, shavings and excess gold produced in this factory per week. In one year, then, at least 400 kilos of gold waste, worth more than 22 million euros, are recycled. At least? It can be as much as 20 kilos a week, I am assured. No one here is surprised about that. Perhaps it’s because big manufacturers like Patek Phillipe or Rolex have their headquarters only a stone’s throw away?

By the way, I know of only one manufacture that makes its own gold, and that is Rolex. All the others, even if they sell and process exclusive alloys with proprietary names, have them cast into the desired shape by subcontractors and receive them as long, round or square bars as so-called extruded goods. This is also the case with Piaget, although the recycled gold is sent back to the Richemont Group’s own refinery in exchange for pure new goods. This is because impurities in precious metals are removed at a refinery. New however is relative: as CEO Benjamin Comar will tell me a little later, Piaget is not only a recycling champion when it comes to waste, but also thinks ahead when it comes to new gold: “100% of our fine gold is supplied by our Group-owned refinery, which supplies us with new, RJC COC-certified gold as a supplement.” RJC stands for the Responsible Jewellery Council, an association of companies from the gold and diamond end industries with the aim of ensuring ethical and environmentally compatible processing along the entire supply chain. A strong message for an industry that likes to keep quiet about how resource-consuming the production of gold from mines is.

From the outside, you can hardly distinguish such a gold rod, as is proudly presented to me a short time later, from similarly shaped parts made of brass or aluminium from the hardware store. Aside from the almost inconceivable weight of such a rod, it is even more inconceivable that precisely this material, which has been driving mankind completely crazy since time immemorial, has been mastered by Piaget in a way hardly comparable to practically any other manufacture in the world.

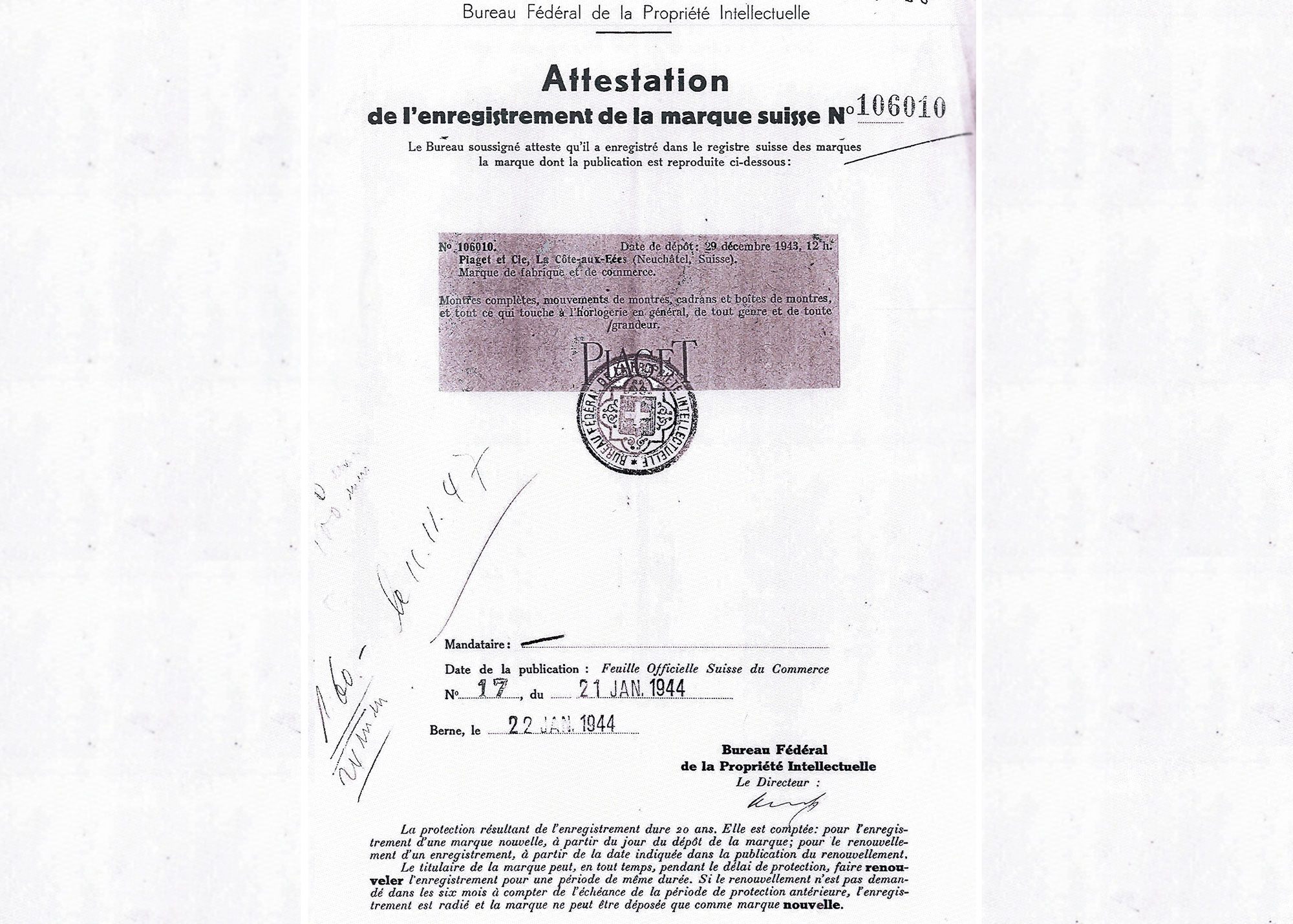

Gold, or rather money and even coins, are a good keyword for this manufacture whose name is already connected with the collection of money. For the family name Piaget, which first appears in the 16th century in the Swiss Jura, goes back to the French verb peager, meaning to collect tolls.

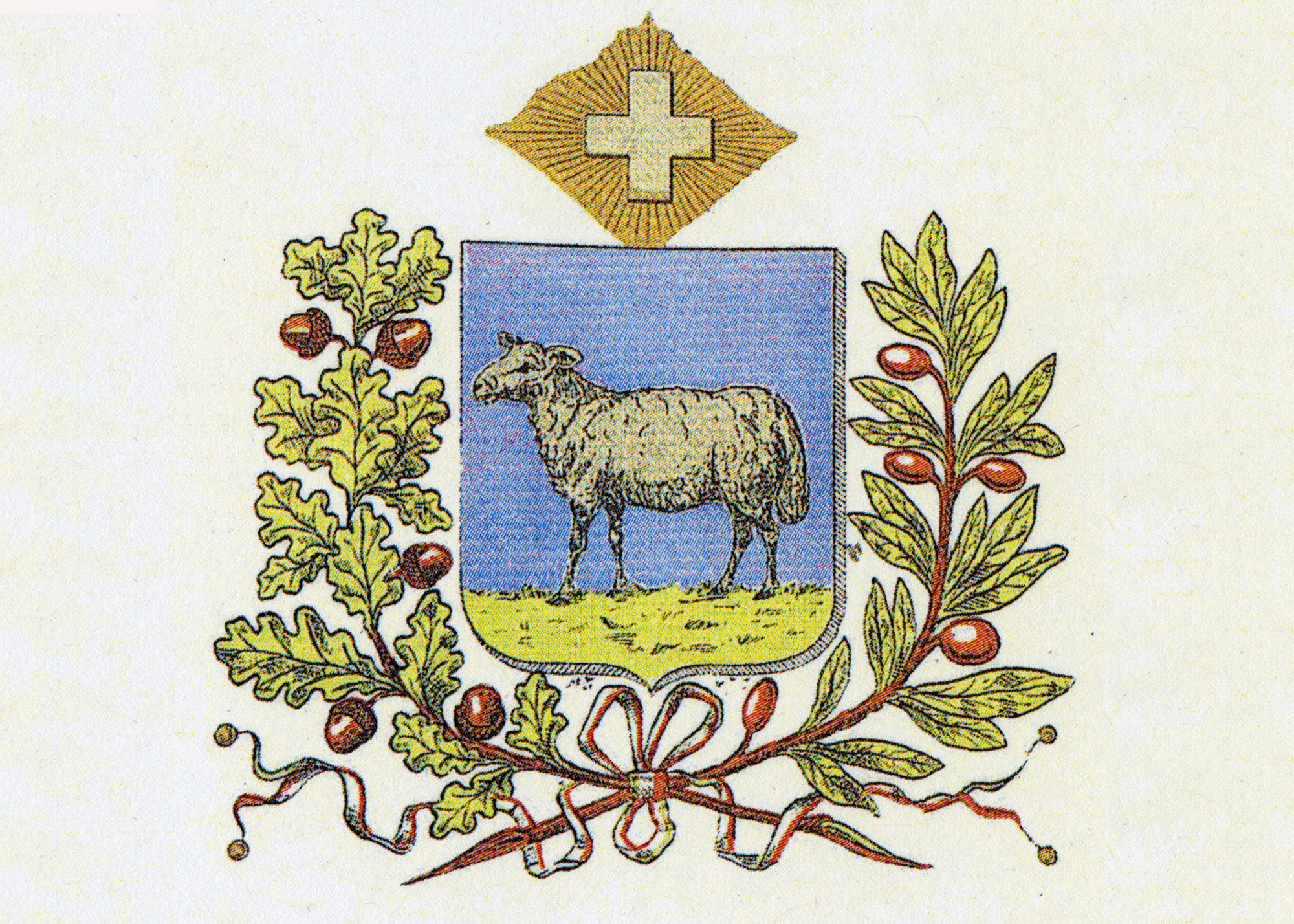

In the 17th century, the family’s ancestors settled in the small farming village of La Côte-aux-Fées at an altitude of around 1000 metres, a few kilometres from the French border and about an hour and a half’s drive from the second production site and current company headquarters in Geneva. The name of the village means ‘sheep grazing on the slopes’. And if 19-year-old Georges-Édouard Piaget had not founded his first shop right here, in the middle of nowhere in 1874, the world would not even know the town’s coat of arms, which is adorned with – nomen est omen – a shaggy sheep.

The character of this man, who set out with a vision that could have come straight out of a marketing textbook today, can be judged by no one better than Jean-Bernard Forot, who not only headed Piaget’s Marketing and Design department for 15 years, but has also been overseeing the history of this brand as Head of Patrimony since 2021 – and knows it like no other. He is still impressed by the entrepreneurial courage and foresight of the young company founder. To put it in perspective: Piaget’s origins lie in the times of the industrial revolution in the second half of the 19th century. It was, of all things, the cheap, pre-industrially produced watches from the United States that plunged Swiss watch production, which was predominantly based on manual labour, into its first major crisis. Too many watchmakers, too high prices, and flagging demand led to a fierce cut-throat struggle.

Jean-Bernard Forot

Head of Patrimony, Piaget

“Piaget’s founder focused on quality rather than volume and invested all his capital and talent in the production of high-end components for mechanical wristwatches. His passion was the slenderness of components.” Meanwhile, his motto still drives each of the approximately 390 employees in Geneva and La Côte-aux-Fées today: ‘Always do better than necessary.’

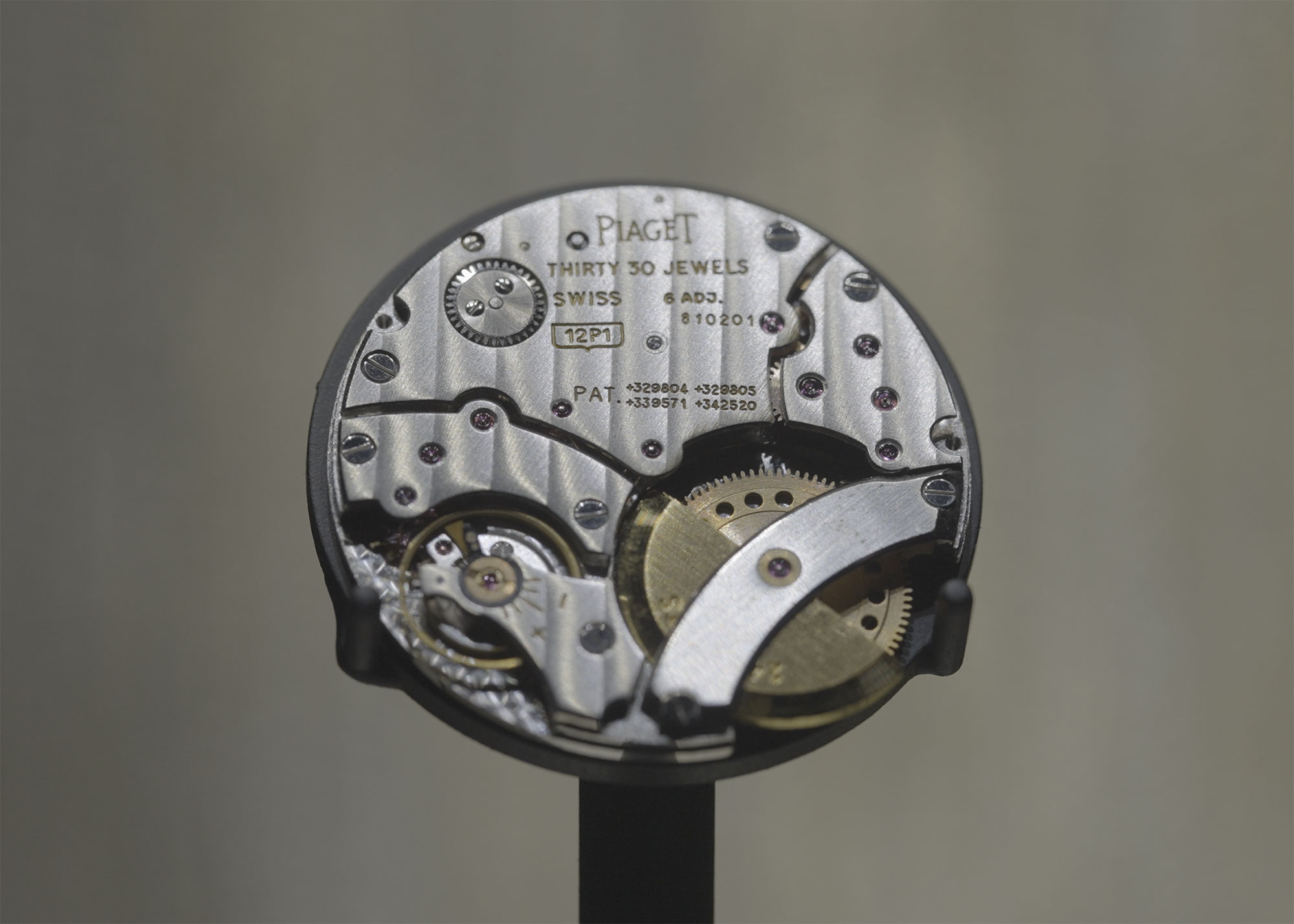

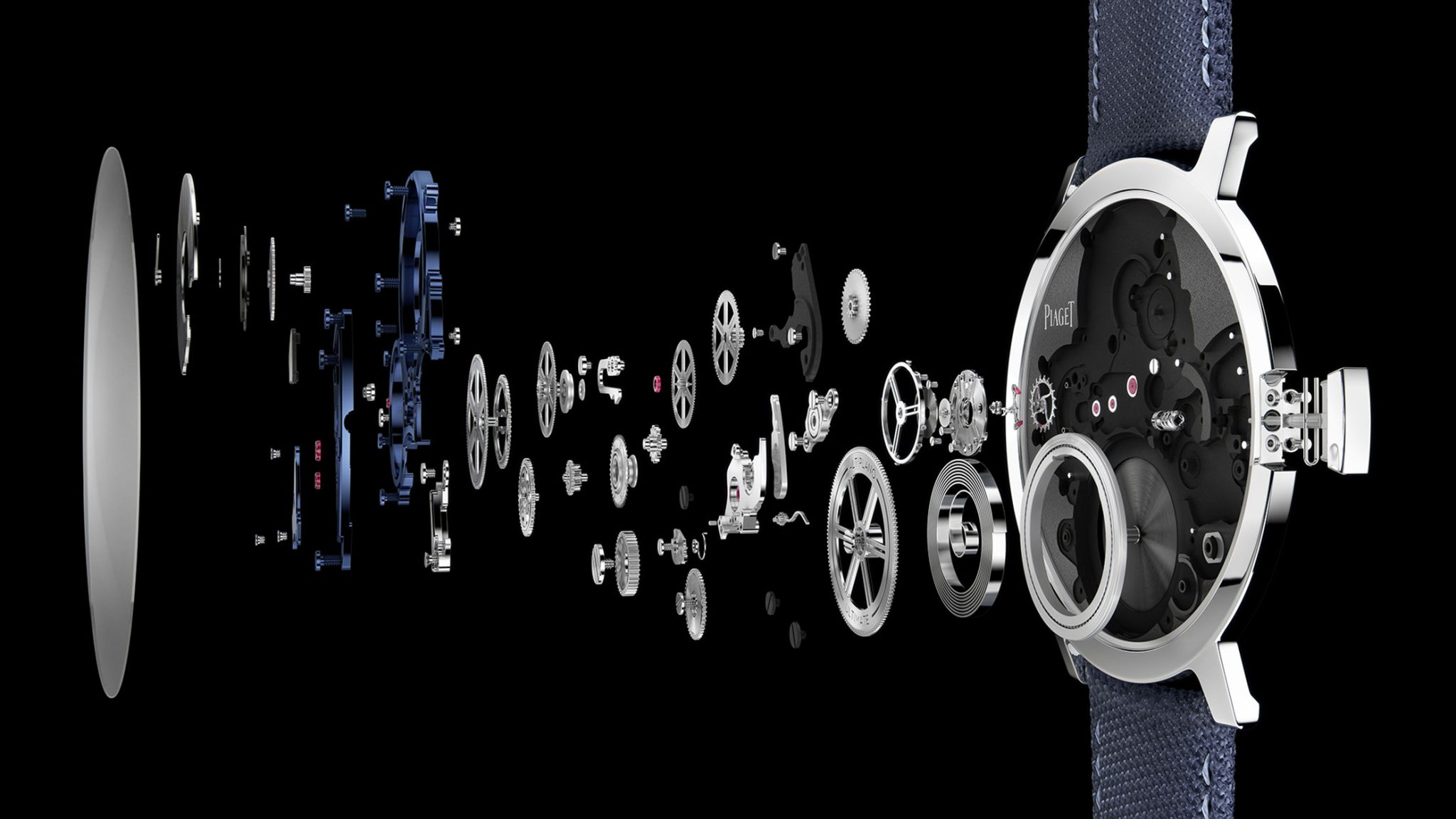

Mr Piaget would be awestruck to see what has become of his vision of yesteryear. Across the street, where the family’s founding house still stands today (albeit occupied by another family), are not only the crème de la crème of mechanical watches such as ultra-flat minute repeaters and tourbillons developed and built in the manufacture. 148 years of watchmaking history have been written here, from famous calibres such as the 9P, which made history in 1957 as the thinnest hand-wound calibre with a thickness of 2 mm, to the movement of the Altiplano Ultimate Concept of 2018 – a world record-holding automatic watch that was presented as a prototype in 2017, and is as thin overall as the movement alone of its famous predecessor presented sixty years earlier.

When you enter the 12,000 square metre production halls of the Geneva headquarters via a large free-floating entrance bridge, you feel as if you are stepping onto a giant spaceship. This bridge is to be understood symbolically. From a bird’s eye view, the building with its circular perimeter road, inaugurated by the then-CEO, Leopold Metzger, in 2001, is reminiscent of a gigantic clock. Dive into its movement, I am greeted like an old friend by today’s CEO, Benjamin Comar, who previously led the jewellery and watch division at Chanel for 12 years on its journey from a simple establishment owner to a manufacture.

Geneva is the nucleus of his company. Here, you find not only all the supporting business departments such as sales, distribution and marketing, but also the production of gold cases and bracelets, the jewellery atelier, as well as the design and development teams. In this case, the heart beats above the head: high up in the Swiss Jura, in La Côte-aux-Fées, its watch movements are brought to life. Comar enlightens me as to how the former subcontractor and parts manufacturer became a full-fledged watch manufacture and at least as important a jewellery manufacturer. “Unlike many jewellers, who at some point also wanted to make mechanical watches, it was the other way round at Piaget: until the 1940s, Piaget mainly made mechanical watches; only later, due to ultra-flat and large dials, did jewellery watches and even jewellery come along.”

Piaget enjoyed a reputation for many decades as a supplier of the finest components, especially escapements, for mechanical watches. The family remained as modest as it was discreet and did not even sign its own watches, which it also began to manufacture. At the same time, they supplied all the big names of the time, from Breguet to Rolex, Cartier, Audemars Piguet, Zenith, Vulcain and Longines to Ulysse Nardin, Vacheron Constantin and Omega, to name but a few. The entire industry became enamoured with these calibres, measuring only around 2.4 millimetres in height, to emerge from the tiny, sheep-filled village.

The modesty of this family is also reflected in the brand itself, which developed late. In 1926, the first pocket watches were sold under their own name, yet it was not until 1943 that Piaget was registered as a trademark.

How good they really were was proven in the 40s by the so-called coin watches: Piaget was already then able – which is sensational to this day, considering the technical means of the time – to accommodate a complete movement in a normal gold coin and make a watch out of it. The enormous potential of ultra-thin watches became apparent early on.

During the midst of the Second World War between 1937 and 1945, the first manufacture building was erected in La Côte-aux-Fées, where to this day complicated movements are developed and assembled and the restoration department is located. This manufacture already housed more than 200 employees by the end of the Second World War, in the middle of a tiny village in the Swiss Jura. In the area, the company headquarters was simply referred to as ‘the Factory’. The first stand at Baselworld, the most important watch fair in the world at the time, was in 1946.

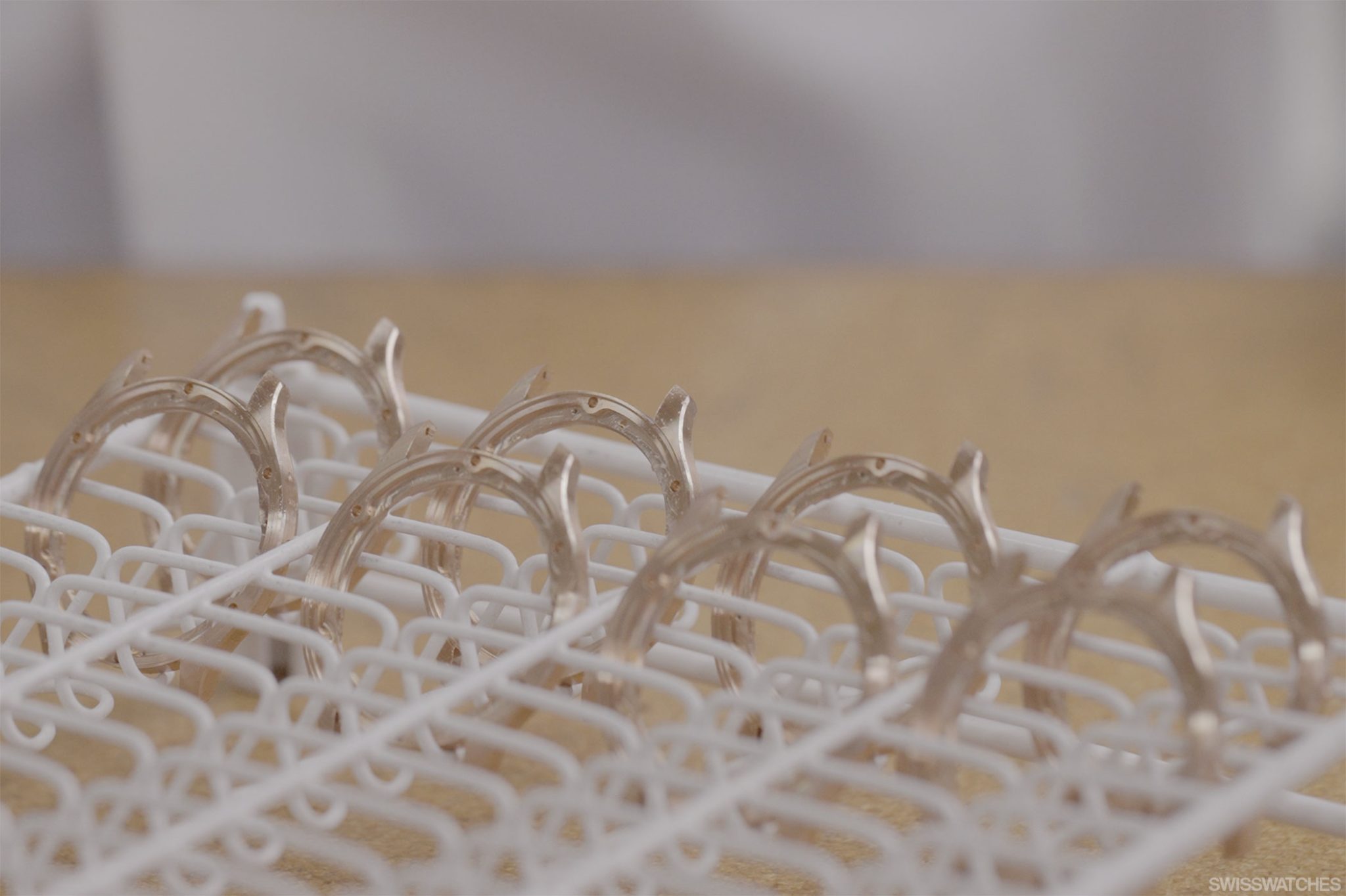

CEO Comar leads me through the light-flooded halls extending over several floors. In the largest one, there are numerous CNC machines upon which his employees produce the gold cases, plates, bridges and bracelet links. “We have the know-how internally to produce all the parts of a watch ourselves, even if we don’t want to produce them all ourselves. But having the know-how is crucial.” And that know-how is vast: complete movements, cases, bracelets, jewellery and high jewellery pieces, are made in-house at Piaget. This is because the company is also a fully-fledged jewellery manufacture: diamond sourcing, cutting and processing are all part of the process, as are highly specialised stone-setters who are even able to set movement bridges with precious stones. Around 40 different crafts, some of them centuries old, from engravers to stone setters to polishers, are practised here.

Looking at the modern Piaget watches such as the Gala or the ultra-thin Altiplanos, the CEO is particularly interested in the combination of the two skills of producing extremely filigree movements and high-quality jewellery. As Comar explains, “The art is to merge the savoir faire for individual areas more and more; we cultivate a very integrated way of working.” From what I’ve seen so far, coupled with Piaget’s incredible watchmaking knowledge, this is rare for an industry that usually only makes jewellery or only watches.

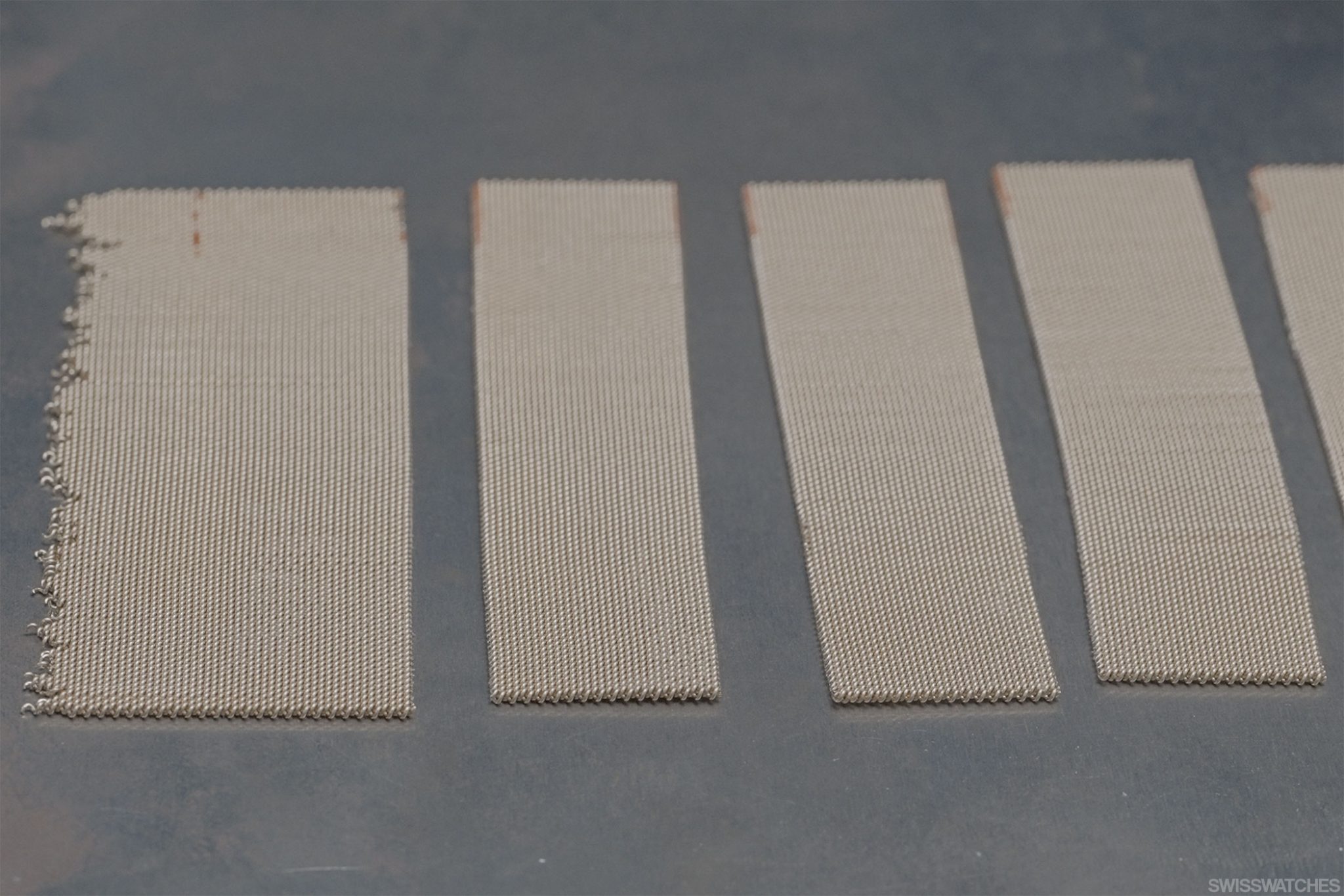

Remi Jomard, Director of Research and Development, who also joins us, is even more explicit: “To really claim to be a manufacture, you really have to be able to make watches from raw material to finished product – and that’s what we do here. Only the ultra-flat and complicated movements are still assembled at our old headquarters in La Côte-aux-Fées. On our milling machines in Geneva, we work from the gold blank to the finished case, building bridges and individual parts, alongside our High Jewellery department.” To this end, Piaget has developed a very precise knowledge in the production of metal bracelets, especially in gold.

The best thing for collectors is that if you look at the development of these movements, you will see that Piaget has always developed its own movements and complications, especially the two most important ones, the tourbillon (starting with the shaped movement of calibre 600P, only 3.5 mm thin in 2003) and the minute repeater that followed in 2013 (the calibre 1290P, 4.8 mm), which were the thinnest on the market at the time of their invention and are still among the thinnest anywhere. Even with quartz movements, they were among the pioneers on the market – but more on that later.

If you look at the family tree of movements that are relevant to Piaget today, you will find the hand-wound calibre 9P from 1957, mentioned at the beginning, with a movement thickness of 2 mm, which was unique at the time, alongside the family tree of thin automatic movements, whose roots go back to the calibre 12P (also a world record holder) in 1960. Both calibres found their descendants in improved movements with the acquisition of Piaget by the Richemont Group in 1988: The 2.1-mm thin base calibre 430P with manual winding was introduced in 1998, the same year that the calibre 500P with central rotor appeared.

Piaget Calibre 9P & 12P1

Piaget Calibre 430P and 500P

The most important milestone since the 2000s has probably been the 1200P model introduced in 2010 to mark the 50th anniversary of the 12P calibre, which continues to power Altiplano watches to this day and, when it was unveiled, represented another world record in the company’s history. My former teacher, the watch expert Gisbert L. Brunner, describes the ground-breaking movement like no other. Since 1997, 13 hand-wound movements and 14 automatic calibres have been developed, including six skeletonised models alone, four tourbillons, a flyback chronograph and a perpetual calendar. If that were not enough, the company can also look back on ten world records for the 21 ultrathin movements it has developed itself, the most recent of which was the Altiplano Ultimate Concept in 2018 (which has since been reset by Bulgari and Richard Mille).

Piaget manufactures different parts of the movements itself, from the plates to the bridges to the escapement system. In addition, the gold cases and precious metal bracelets, some with historic decorations, are manufactured in Geneva, as are some dials and even screws. Research and Innovation director Jomard’s view of the development of the resulting ultra-thin watches is interesting: “We consider it our very own form of complication to produce ultra-thin watches. Even though we honour all the classic complications, we believe that slimming down such movements is an art in itself, because it’s not uncommon for us to push the limits of physics.”

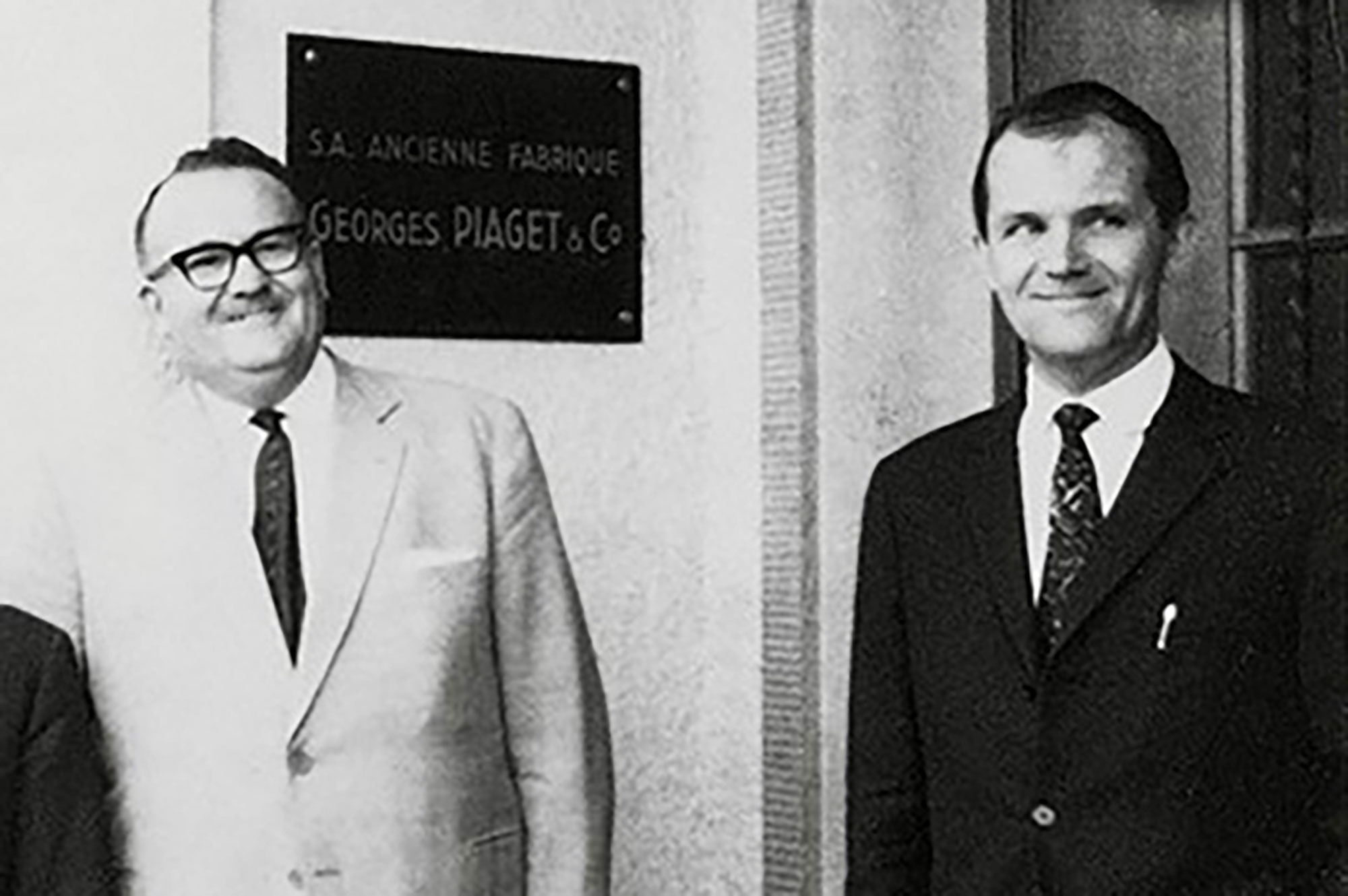

Pushing the limits is the right keyword: when the second generation passed the company on to the third after the war, two people stood out in particular: Valentin Piaget, who had both the skills of an engineer but also the visionary power of an artisan, and his brother Gerald, whose strengths lay in commerce and finance. This combination would be crucial in helping Piaget ascend the Olympus of watchmaking within just a decade. The most important expression of this rise was the presentation of the first ultra-thin movement for wristwatches, the Calibre 9P, in 1957.

This suddenly opened up new possibilities for watch design: wide but extremely flat movements allow a much more creative approach to dials and cases. And when the dial gets bigger, the bracelet can also get wider, which the Piagets recognised as a playground for further creations. A constant process of discovery that can be seen very clearly in the historical watches.

Head of Heritage Forot recalls: “Piaget supplied the whole industry with movements, but at the end of the 1950s, it decided to equip only its own watches with the 9P and 12P calibres and, what’s more, to produce only gold and platinum watches.” The brand’s positioning was thus clear: Piaget had once again decided against mainstream and in favour of luxury.

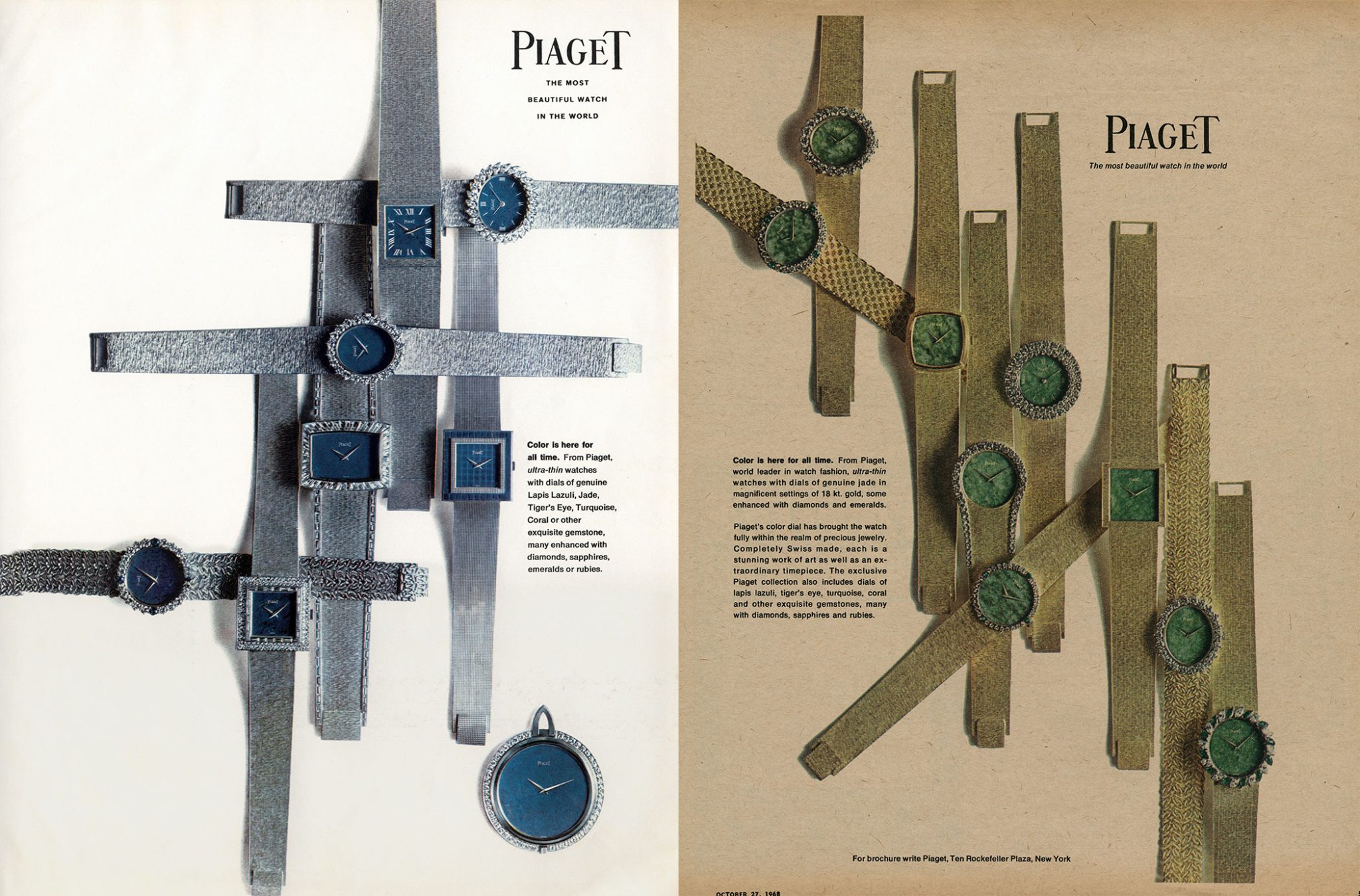

From the 50s to the 70s, the number of models exploded. Piaget integrated further craftsmanship into all elements of these watches: elaborate gold engravings, diamond bezels and coloured stones for the dials. They created something that had never existed before. At that time, most ladies’ watches were plain and thick and had very small diameters. Piaget offered ladies’ watches that were easy to read and at the same time much more elegant. In addition, they consisted of elaborately crafted gold cases and soon diamonds and coloured stones were added. The attention of the elites was awakened.

These post-war elites differed above all from the aristocracy and royalty as in the decades before: for the emerging jet set, Piaget’s style was so attractive above all because it was fundamentally different from that of the previous generation. The rich wanted new luxuries and no longer the old ones of the traditional aristocracy.

It did not matter that the watches were not primarily functional, because Piaget’s reliability was known to all. Piaget made a conscious decision to become a brand of distinction, and of course it did so with ultra-thin and ultra-precise movements as its backbone. It was the outstanding quality combined with enormous creativity that generated enormous visibility for Piaget and helped the brand break into the luxury sector.

The stars of Hollywood became aware of the brand through the fourth generation of the Piaget family. The decisive role here was played by Yves Piaget, who stepped up as brand ambassador and guided the fortunes of the manufacture for over four decades. He not only began to promote the brand, but also recognised the enormous potential of gala evenings and customer events. That might sound self-evident today. Suddenly, film stars were mingling with traditional clients, amongst musicians, artists and business people. Magazines all over the world covered these events, which in turn made attending them even more desirable for actors.

Crucially, for Head of Heritage Forot, “The stars were clients, not paid brand ambassadors.” The famous book Piaget – Watchmakers and Jewellers, published in 2014 by Abrams in New York, has a lot of stories to tell: for example, the tale of Elizabeth Taylor’s assistant, who asked for watches in the Geneva boutique in 1971, which Yves Piaget drove up to the actress’s suite at the Gstaad Palace shortly afterwards. Many such anecdotes about former Piaget customers are as flamboyant as the brand itself.

Incidentally, the decoration of a bracelet that adorns a watch by Jackie Kennedy is also called ‘Palace’ and remains a specialty of the house today. Jean-Bernard Forot proudly displays the original watch when he visits his archives: “She bought the watch in Beverly Hills in Los Angeles, in 1967, when it still bore the Kennedy name.”

Jacqueline «Jackie» Kennedy

Credit: Mark Shaw / AP

For him, this watch embodies all the values that still apply to Piaget today: “We have four design pillars in the manufacture. The first is in the material gold, the second is the light that shines through our diamonds, the third is the movements themselves, and the last pillar is the colour found in stones.” The Kennedy watch features a dial made of jade, a coloured stone, and is also set with diamonds and emeralds. It is these stories that have given the brand a meteoric rise. The watch Liz Taylor ordered in Gstaad was an elaborate cuff watch, more of a bangle in gold that could also tell the time and that came from the legendary 21st Century Collection, where the Piaget family had given their artisans carte blanche.

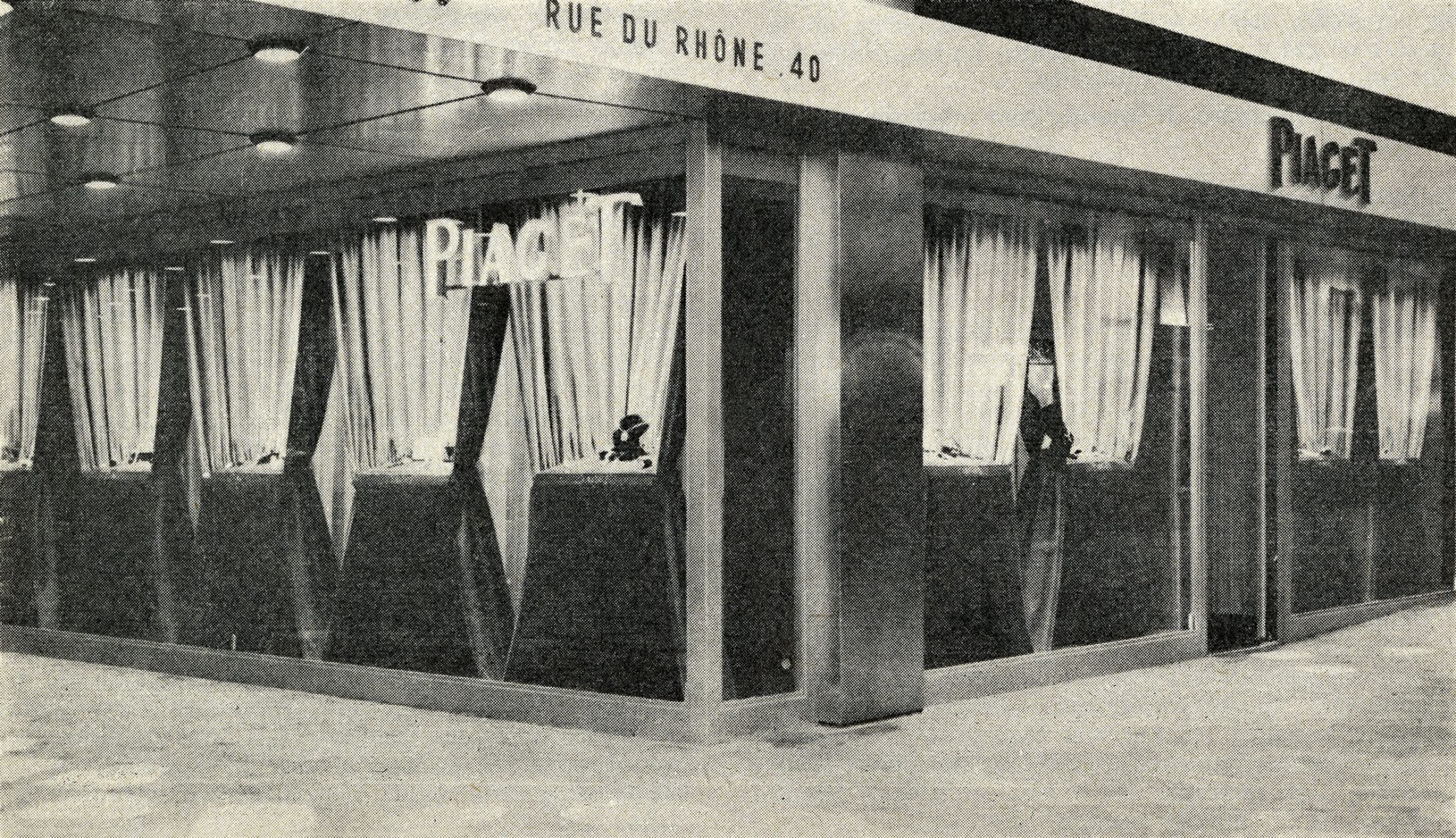

The credit of being the first to truly take women seriously as customers in the watch sector belongs to Valentin Piaget, because he was both a watchmaker and a goldsmith. Under the impression that they operated completely differently from the rest of the Swiss brands, they also wanted to express this, and at the end of the 1950s they opened what would still be called a real showroom today: the Salon Piaget. Primarily, it was not about sales. It opened in 1959, had tiny windows, only a few pieces were shown in it, and it had no sales counter. Forot describes the hustle and bustle of the stars back then as follows: “People sat down, talked about art, and then incidentally about watches. Today, you have to think of it more like an art gallery, because at Piaget they were convinced that the craftsmen were artists, just like famous sculptors or painters.”

Salon Piaget – 1959

It was the way Piaget worked with his creations that really made many artists sit up and take notice: they sensed this creativity and wanted to connect with it. Salvador Dali was one of them. Forot reports: “A man of great creativity and even greater ego, he claimed for himself the right of kings to mint his own coins. He decided to create his own currency, and had it made in Switzerland. These coins were not meant to be currency, but works of art, because they were numbered.”

Piaget was given the right to create jewellery with the coins, but was not allowed to damage them. Combining his skill in setting gems with the coin-watch, Piaget perfected this art. Forot: “This is where 20 years of work paid off: what was once a showcase of coin watches became a timeless work of art, sold from 1967 to 1982.”

Pop art icon Andy Warhol knew Yves Piaget from various events and bought his very expressive Piaget in 1974. Because it housed one of the first quartz movements, the Beta21, which Piaget had co-developed with other companies such as Patek Philippe and Rolex, it wasn’t quite as thin, yet Piaget reissued it as an automatic watch in 2015 in a 28-piece special edition, followed by another edition in 2017 with a meteorite dial. Forot also knows how the original watch came into Piaget’s collection: “The Piaget family bought back four of the seven the pieces Warhol had bought, at auctions. In 1988, a year after Warhol’s sudden death in 1987, several Piaget models were among the 313 watches sold at auction from the artist’s estate.” It was also the first time that the family began to reacquire historical pieces.

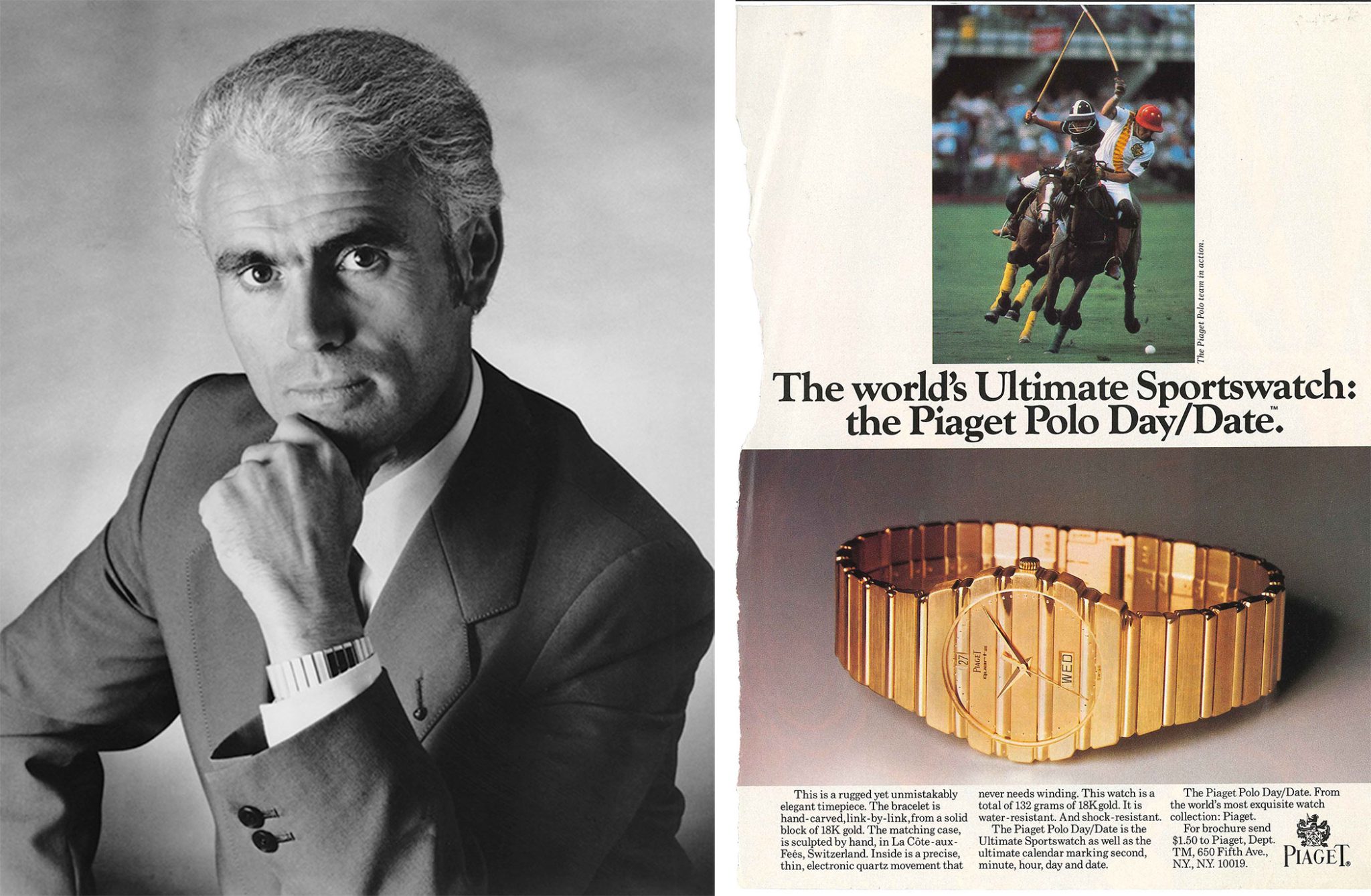

The list of celebrity clients is so long that you’d almost think Piaget society deserves its own movie. While Alain Delon was sporting his Calibre 12P automatic watch, Gary Grant was so proud of his ultra-thin Piaget that he proudly presented it to Yves Piaget during his visit to the USA. While Gina Lollobrigida traded her Piaget for Fidel Castro’s Seiko when she visited Cuba in 1979 for a documentary on the Cuban revolutionary, Yves Piaget was preparing his next watch revolution: the Polo watch, which took a completely new direction for Piaget. The first Piaget watch with its own model name was presented in the same year.

The Piaget Polo no longer really resembled a classic watch; it was more like a bracelet with an integrated watch. Made of solid gold, it featured an in-house developed quartz movement in the late 70s, which was of course ultra-thin and ultra-precise.

Yves Piaget made sure that this watch got its name because actually, Piaget watches didn’t usually have a name. His family resisted, for at Piaget, style and lifestyle had been enough until then, and a name for products had never been necessary. But the American market demanded it. Since he was a big horse fan, Yves decided on the name Polo. At the same time, it was the first sponsorship of the house, simply because polo, as the sport of kings, was also a very elitist sport at the time. Artist Andy Warhol also owned two different models (there was also a rectangular Polo). The style of this watch attracted the attention of many celebrities, from Swedish tennis player Björn Borg and his wife to actors Roger Moore, Ursula Andress and Steve Martin, all of whom wore the Polo.

The watches in question include the Piaget Polo small model Reference 8131 C701 in 18-carat yellow gold with a round case and the Piaget Polo large model Reference 7131 C701 with a square case in 18-carat yellow gold.

Jazz legend Miles Davis, who reportedly travelled to his gigs with a briefcase containing a selection of different watches, only to choose one very shortly before the performance, was among the first to wear it. If you have the opportunity today, you should definitely take a look at the two early models at an auction.

In 2009, the Polo Forty-Five followed 30 years after the launch of the original, perhaps with an unusual design for today’s tastes, but it was the bridge model for Piaget’s future and not only finally housed the manufacture’s first chronograph calibre developed in-house, but also broke with the company’s tradition of using only precious metals: the case was made of titanium. The calibre 880P used in it and presented in 2007 not only had a power reserve of 50 hours (when the chronograph was started), but also a flyback mechanism, a second time zone and was only 5.6 mm thin. In 2016, the Polo S followed – the forerunner of today’s model in a contemporary design – which was not without controversy at the time of its introduction, but eventually caught on. Today, it is the company’s most important sales driver, alongside the ladies’ watches and jewellery creations, of course. Piaget’s first Polo in steel is still fitted with the 1110P and 1160P calibres as chronographs today.

Today, it may surprise newcomers that Piaget chose a quartz movement, of all things, for the Polo in 1979. But it was the trend of the time, and the Piaget family had already collaborated ten years earlier on the creation of the famous first Swiss quartz movement, the Beta 21 calibre, in a consortium with Rolex and Patek Philippe, as mentioned above. Rolex even ended up selling over 100,000 of its quartz watches, now collectors’ items themselves, which Rolex called Oysterquartz.

Piaget had only one problem with this movement: it was simply too thick for the company’s elegant cases. This can be seen particularly well in the model bought by Andy Warhol, which covers up its thickness with a particularly clever design and is now found in the collection – mechanically, of course – as the ‘Vintage Inspiration Watch’. The very fact that the Beta 21 calibres were too large for Piaget’s ultra-thin models was sufficient incentive for the company to take a new path. In 1976, Piaget presented the Calibre 7P, a quartz movement that was only 3.1 mm thick and had exceptional precision thanks to 900 transistors. Not only is the Calibre 7P the smallest quartz movement of its time, it enabled Piaget to weather the storm that shook the Swiss watch industry from 1975 to 1985. It is precisely this calibre, therefore, that has historically been justified in residing in the Piaget Polo.

To this day, Piaget is probably the only brand that has truly married watchmaking, jewellery and craftsmanship, or at least in a completely different way than classic luxury brands like Cartier have done. For Yves Piaget, a watch “first and foremost is a piece of jewellery” – a sentence that you have to let melt on your tongue, especially today, in times of smartwatches.

Since 1988, Piaget has been working on its future as part of the Richemont Group, with a total of almost 50 watchmakers, including seven master watchmakers, at both sites. They are tirelessly pushing forward the miniaturisation of watches, technical complications, but also their individualisation.

How did this come about? As early as 1988, they had joined the Cartier Group, in which Yves Piaget remained active as president. In 1993, Piaget merged with Cartier to form the forerunner of the Richemont Group, the Vendôme Luxury Group. Incidentally, Yves Piaget has remained loyal to the company to this day as a brand ambassador, now being aged 80.

Together with the most famous of its showrooms in Geneva, Piaget sells its products in Europe in 11 exclusive boutiques, including the Place Vendôme in Paris. Wempe and Bucherer, among others, stock Piaget watches and jewellery in Germany. Worldwide, Piaget has a network of 134 boutiques, most of them in Asia and including 68 integrated shops in the world’s most famous shopping centres such as Harrods in London or the Galerie Lafayette in Paris. Those who want to protect the climate and their travel budget have been able to shop online at Piaget for exactly 10 years; Net-a-Porter and Mr Porter also carry Piaget products.

Former CEO Leopold Metzger, who led the company for almost 20 years from 1999 to 2017 before being succeeded by Chabi Nouri and, in the summer of 2021, by Benjamin Comar, once pointed out: “We were one of the first watch brands ever to have our own boutique back in 1959.” This wealth of experience with prominent customers is not to be taken away.

Benjamin Comar

CEO, Piaget

Piaget is still a household name for the rich and famous, only nowadays, they don’t parade their luxury around so obviously: 15 per cent of the total production alone are elaborately made-to-order pieces that customers order from all over the world, as CEO Comar reports. “Our customers definitely know their way around jewellery and watches. I always say they are in the know – and the how.” But he stresses that every Piaget customer is equally valuable to him. When asked in farewell which of the watches from the current collection most represent Piaget for him, he answers without thinking twice: “My Altiplano Ultimate with the calibre 910P, which I wear a lot. It’s a great everyday watch, which you wouldn’t think at first glance because it’s so thin.” Second, he chooses the fairly new Polo Skeleton, which for him has the right twist for the 21st century. Launched last year, it is powered by the skeletonised, ultra-thin Calibre 1200S, introduced back in 2012. Third on his list is the Limelight Gala, powered by either a quartz or automatic 501P1 movement. For Comar, it is “the quintessence of a jewellery watch. It is very extravagant and therefore what Piaget stands for.”

For Remi Jomard, Head of Research and Innovation, the calibre 1110P that ticks in the Polo stands out alongside the Altiplano Ultimate. “Whereas with the former model only the smallest quantities are realised, with the calibre 1110P it’s already a matter of production where we rely more on industrial methods.” This calibre is therefore also produced in another production facility, which is operated jointly by all Richemont brands. Piaget, like all Richemont-owned manufactures, is naturally silent about the number of pieces produced. Even though experts estimate that around 25,000 to 30,000 watches are produced annually, CEO Comar remains as silent as the blind monk in the novel The Name of the Rose.

Remi Jomard

Head of Research and Innovation, Piaget

By the way, if you are now wondering where the botanists mentioned at the beginning of this article came up with the Piaget rose, we must return to Yves Piaget. As a man who has nurtured a passion for rose breeding since childhood, he once donated a solid-gold prize for a competition named Concours des Roses Nouvelles de Geneve. In 1982, the famous rose breeder Alain Meilland dedicated the winning rose with its 80 tight petals, delicate colour, and bewitching fragrance to Yves Piaget as a tribute to his generous and passionate support. This later inspired Jean-Bernard Forot to create the Piaget Rose jewellery collection.

“We will continue the journey towards ultra-thin movements; that is our signature. The challenge here is to marry these models with the world of complications.” On the other hand, he believes skeletonised watches will be an exciting field in the future, “firstly because we have the credible story to go with it, and secondly because transparency is a great way to make real craftsmanship visible to everyone.”

When asked about the ever-increasing competition from ultra-thin watches and movements from rivals such as Bulgari and Richard Mille, who, as mentioned, have since overtaken several Piaget world records, the reaction in Plan-Les-Ouates is surprisingly calm. Indeed, supplies Comar, “We see this as a creative exchange. We are very proud that this trend exists, because we set it.” And his R&I boss, Jomard, adds: “The biggest difference between other manufacturers and Piaget is that with us, technology and design are combined into a harmonious whole.”

This also applies to future world records, which are undoubtedly being worked on for the company’s 150th anniversary, and which will be celebrated next year. Jomard spells it out: “It is always possible to push the limits of physics further. But the point of a mechanical watch is to wear it, and after a certain moment, watches just get too thin to be comfortable wearing them.” His superior adds, “We will of course continue to develop our Ultimate, but the idea is not to just break world records. We want to make wonderful watches.” If this ambition remains, there is no need to worry about the next 150 years that lie ahead at Piaget.