The A. Lange & Söhne ZEITWERK HONEYGOLD "Lumen" uses sapphire glass to expose the luminous numerals on the discs of the digital time display.

Where do the boundaries of feasibility lie? Who pushes these boundaries? How many parts of a mechanical watch, in this age of computerised production, are truly made by hand? Every collector with a love of the rare and the exclusive faces this question at some point in their life. This is because the work and lifespan of a genius is immeasurable. Every person who creates extraordinary watches knows this for a fact, sometimes patiently dedicating several years in order to hold a treasured timepiece in their hands.

Exactly a decade ago to the day, George Daniels passed away. He was truly a master watchmaker who never completed a formal education – yet nonetheless pushed the boundaries of mechanical watchmaking to an extent that had not been seen since perhaps Abraham Louis Breguet or fellow Briton Thomas Mudge (who, over 250 years ago, heralded the arrival of portable timepieces with his lever escapement). George Daniels completed a mere 37 mechanical masterpieces throughout his lifetime, including prototypes. Left to his own devices, he trained himself in all 34 trades needed to create them on his own. Through his universal, intense study of mechanics, he also made a revolutionary breakthrough, inventing the first lubrication-free escapement system for mechanical watches, which he termed the Co-Axial escapement and was eventually acquired by the Swatch Group for OMEGA in 1999.

In September 2011, in my capacity as Watch Editor of GQ magazine, I sent a writer along with a photographer to the remote Isle of Man, lying between England and Ireland, to visit the genius himself. No one in our editorial department suspected that we would be the last journalists to speak with this modern Michelangelo of watchmaking. Today, in memory of this great man, whose incomparable life’s work and books inspired a whole generation of master watchmakers, we are republishing this article by Serge Debrebant, together with pictures by photographer Olivia Arthur.

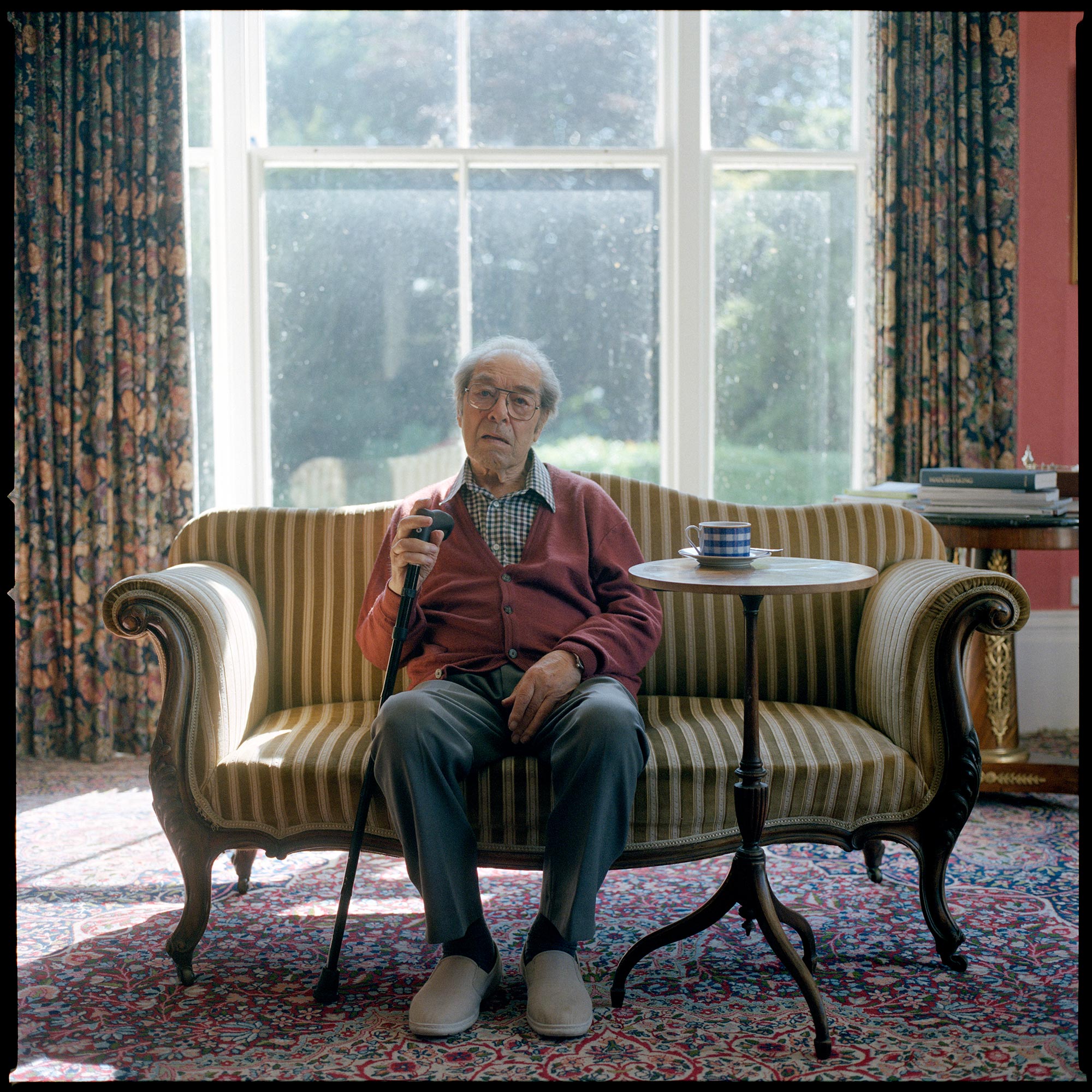

George Daniels, 2011

© Credit: Olivia Arthur / Magnum Photos / Agentur Focus

The article’s headline at the time was The One and Only. We travelled to the Isle of Man again this autumn, and – following in Daniels’ footsteps – visited his only student. Roger W. Smith, who now continues Daniels’ legacy, is today himself one of the most sought-after independent watchmakers on the planet. You can watch our film here:

The workshop is only a few meters from the house, yet George Daniels has not entered it for a year. When he tries to take the step up to the entrance, he finds it difficult to lift his leg. His secretary holds him by the arm and helps him through the door. In the entrance hall of the bungalow, there is a bicycle. Behind it stretches a long, narrow room. Leaning on a cane, Daniels enters it.

Aside from the cobwebs on the milling machine, the workshop looks as though he had used it only yesterday. Minute wheels, balance shafts and pallet forks lie on the worktops. In the past, Daniels would sometimes work here for 36 hours in one sitting – alone, without a radio, and so absorbed in his work that he would remember nothing of it afterwards. He probably spent more time in his workshop than anywhere else. “Here, I listened to the silence,” he says. “Even that was sometimes too loud for me.”

Left: George Daniels workshop. Right: Gear train – scattered components of a watch movement on which George Daniels worked for more than ten years (2011)

© Credit: Olivia Arthur / Magnum Photos / Agentur Focus

Daniels is considered the greatest watchmaker of the present day. The 85-year-old Briton has built 37 watches by hand, and when one of them comes on the market (something that happens rarely), it easily fetches six-figure sums. Most importantly, Daniels developed a new mechanism for the escapement, a key component of any mechanical watch. The previous person to succeed in this area was Thomas Mudge, 257 years ago. Among collectors, Daniels is therefore – even if it sounds trite – a living legend.

“I’ve been thinking about what people say about me, and I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s true,” Daniels says, after taking a seat in a plush red upholstered chair. Since Daniels moved to the tax haven that is the Isle of Man 29 years ago, he has lived in an upper-middle-class villa with twenty rooms.

When listening to his conversation partner, Daniels tilts his head forward. Meanwhile, the bust of Daniels on the cabinet, created by pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi, gazes into the distance like a general.

“I’ve been thinking about what people say about me,

and I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s true”

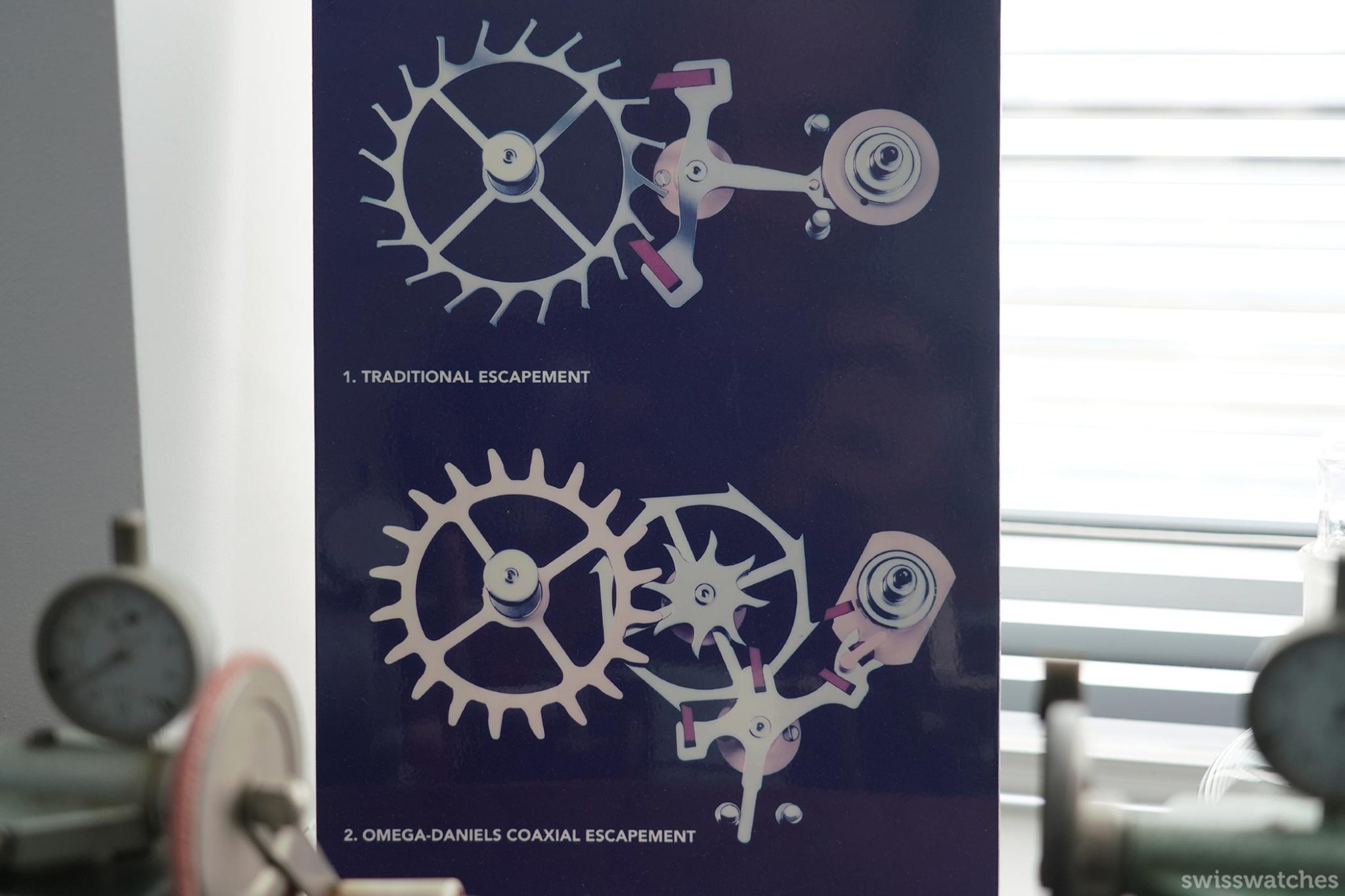

Meanwhile, on the antique side table there sits a model of his greatest invention, the Co-Axial escapement. Escapements form the link between the gear train and the escape wheel. While most Swiss manufacturers use an escapement with a single escape wheel, this model shows one with two wheels mounted one above the other. Friction is so low on this type of escapement that unlike conventional escapements, it does not require lubrication. It is also shock resistant and remarkably accurate.

“I knew immediately that my invention was superior to all the others,” Daniels croaks. A few years ago, he had to undergo throat surgery due to cancer. He seems feisty, even though he’s not well at the moment. Sometimes, he confuses dates or refers to Verdi as an opera singer. The interview was postponed several times because a respiratory infection has been bothering him. “Soon I’ll have gone through all the diseases in the medicine manual,” he says.

That said, Daniels doesn’t let things get him down easily. He has survived worse; a brutal drunkard for a father, a merciless mother, clothes with holes, winters without heating. He was born in London in 1926. At 14, his parents sent him to a mattress factory to help feed his ten siblings. In his autobiography All In Good Time: Reflections of a Watchmaker, he writes of the poverty surrounding his upbringing on paper. But he doesn’t like to talk about it.

He prefers to talk about his first watch. He was five years old when he found it on the floor of the house. Daniels had no idea who it belonged to, yet he opened the case with a bread knife to look at the movement. It had stopped; Daniels stared at the interlocking wheels. Amid the chaos he grew up in, the set order of the mechanics must have felt like a piece of a real home. “For me, that watch was the centre of the universe,” he says.

Almost everything Daniels knows about watches comes from books. He never completed an apprenticeship. After the war, he worked his way up from a simple handyman to a specialist in antique watches. He befriended affluent collectors, advised Sotheby’s, wrote books. In the late 1960s, he received an offer to run the Breguet manufacture and turned it down. “I thought Daniels London would sound better than Breguet Paris,” he says. Daniels set out to build his own watch. He wanted to make every part alone, down to the very last screw.

“It was outrageous, and something that had never happened before,” says Roger Smith, a 41-year-old watchmaker and Daniel’s only apprentice. Smith lives just a few minutes’ drive from Daniel’s villa in a cottage where he runs a workshop. He makes about ten luxury watches here every year. A commissioned piece costs at least 120,000 euros. In contrast to Daniels’, the workshop in which Smith works with five employees has the spotless look of a laboratory.

For him and several other young watchmakers, Daniels proved that it was possible to make a living as an independent watchmaker. “George created a market that didn’t exist before,” says Smith. Daniels’ work was unusual, however, because mechanical watches have been created by division of labour ever since the Renaissance. A 19th-century encyclopaedia lists no less than 34 trades as being involved in the construction of a mechanical watch: spring makers, case makers, guilloche makers – the list goes on. Yet Daniels mastered them all.

Daniels constructed his first watch because he cared about the industry. On December 25, 1969, Japanese electronics company Seiko launched the Astron 35SQ, the first wristwatch with a quartz movement. “It was clear to me that mechanical watches would not survive unless the industry did something about it,” Daniels says as we sit in the living room. Swiss chronometers are allowed to advance six seconds and go back four seconds per day. Daniels wanted to build a mechanical watch that told time more accurately than a quartz watch. He sold one of his first pieces to a friend in London, who took it on a trip to Tokyo. When he returned 32 days later, the clock was off by less than a second.

Interestingly, Daniels did not work from sketches, but rather made them once the watch was complete. “I’m aware that most watchmakers do it the other way around, but I’ve always liked this way of working,” he says. Not being bound by drawings gave him the freedom to try out new ideas. If he made a mistake and destroyed a component, he didn’t throw it away, but laid it to rest in one of his plastic trays that he calls “graveyards”.

The next day, Daniels takes a seat lift down to the basement and opens the door to the vault. This is where he keeps his watch collection and his Leica collection. A nurse helps him take some boxes to the desk in the next room. Here, Daniels takes out the first watch he had been tinkering with for two years.

George Daniels Roger W. Smith Anniversary

© Credit: A Collected Man

Each of the 37 watches Daniels has made over the years took about 2,500 hours of work to complete. In addition to these, there is also his series of “Millennium” wristwatches he made with Roger Smith at the turn of the millennium, plus the “Anniversary” wristwatches that Smith is currently assembling according to Daniels’ plans, which are intended to commemorate the invention of the Co-Axial escapement. Smith will present the first example in November at the famous Saatchi Gallery in London, where the artist Damien Hirst first enjoyed success in the 90s.

George Daniels Roger W. Smith Millenium

© Credit: A Collected Man

Daniels wants to open up the watch to take a look at the movement. After the first attempt, he asks Smith for help as he lacks the strength. He then displays the “Space Traveller“, a tribute to the moon landing, which is considered his masterpiece. The watch displays both solar and sidereal time, bringing the two mechanisms together in a single escapement – a design that, according to Daniels, is unique.

Space Traveller pocket watch by George Daniels

© Credit: Danielslondon.com

He has always been convinced that a watch must prove itself through its technical feats, rather than through a forced design. His own watches have a simple, clear elegance that is reminiscent of the Art Deco style. Daniels cites Breguet, about whom he has written a definitive work, as his role model. Instead of wristwatches, he preferred to make flat, wide pocket watches that fit comfortably in the hand. “You don’t wear a watch just to tell the time, but also so that you can touch it and distract yourself with it when you’re sitting in a tedious meeting,” he explains.

“You don’t wear a watch just to tell the time,

but also so that you can touch it and distract yourself with it“

Aside from one exception, Daniels has never taken commissions for his watches, selling a watch only when it was ready. “It would have been too embarrassing for me if a customer ordered a watch and then turned it down,” he says. Furthermore, he doesn’t find everyone worthy of wearing a Daniels watch. However, one Swiss watch collector once offered him a signed blank check. After some hesitation, Daniels gave in.

In the industry, Daniels is regarded as a brilliant but difficult loner. Even Smith, who admires him and has come to know him as a patient, self-sacrificing mentor, admits that his reputation precedes him as having a “fearsome” personality. Perhaps this is also because he struggled for a long time to convince the Swiss watch industry of the Co-Axial escapement. In a way, it was a clash of two cultures: the uncompromising, eccentric tinkerer versus the manufacturing engineer of a large, old-fashioned industry. For nearly 25 years, Daniels waged a lonely war against what he describes as mental inertia and stubbornness. Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, he met with technicians and bosses from Rolex, Patek Philippe and other manufactures. Yet sooner or later, he fell out with all of them.

This all changed in the 1990s, when a young generation of watchmakers appeared on the scene, full of admiration for Daniel’s work and having grown up with his manuals. Swatch CEO Nicolas G. Hayek, now deceased, acquired the rights to the Co-Axial escapement for OMEGA. In 1999, the first series of watches was launched. Since then, other manufacturers such as Audemars Piguet have also experimented with unconventional escapements.

So, in a way, Daniels triumphed in the end. Nevertheless, he talks about his struggle with the watch industry as if it were still refusing to acknowledge him. He talks about other escapements that lie in his drawer, just waiting to be discovered. “I’ve thought it all through; it’s just a matter of putting the drawings into practice,” he says yearningly.

After half an hour, Daniels packs up the watches again. He has agreed to go to the workshop for a second time, despite the appointment obviously exhausting him. Smith drives him back to the bungalow in the garden in his Jaguar X-Type. On the way, they pass by garages containing classic cars that Daniels restored himself. Among them is a Bentley that set a lap record in the 1930s, as well as a Daimler from 1907.

The workshop appears as deserted as it was the day before. In a plastic tray lies a Rolex in which Daniels installed a Co-Axial escapement in the 1980s. He did the same with all the manufactures he approached. He did everything to prove to the experts that the Co-Axial escapement was not the work of a crackpot.

„The Unfinished” – Daniels had completed 80 percent of it by the time he died

The watch lies silent and still, like most of the watches on Daniels’ estate. The only one he regularly winds is the OMEGA on his wrist. “I check to make sure it’s accurate. I do that with every watch,” he says. Then, he steps up to the green workbench and lifts up a movement he’s working on. A “graveyard” lies on the workbench, littered with watch parts. “The watch needs a little work, but I’ve got 80 percent of it done,” he croaks. Smith tells me later, quite casually, that Daniels has been working on it for more than a decade. He’s not giving up on the dream of finishing it.