Aspiring to become a watchmaker? Wempe supports this forward-looking craft with its dedicated training centre and educational opportunities.

From the clocking ticking above the platform at the railway station to the watch on your wrist, we encounter watches in our everyday life everywhere we go. At school, we’ve already learnt the necessary vocabulary, such as ‘hands’ or ‘hours’, to describe a watch dial. But upon delving deeper into the world of watches, we inevitably encounter numerous technical terms, and consequently many questions related to their meaning. Anyone who has ever studied the product description of a (wrist)watch will likely have encountered the term ‘mechanical watch’ more than once. But what exactly is a mechanical watch?

The chronograph calibre 5370P with split-seconds hand from Patek Philippe.

Besides the quartz (battery-powered) watch, ‘mechanical’ comprises of two watch categories. There are two types of mechanical watches: manual-winding (also known as hand-wound) and self-winding (automatic watch). The type determines how a watch is assembled, handled, and maintained. It is thanks to the manual-winding mechanical watch that these distinctions exist in the first place, as it provided the basis for innovations such as the self-winding (automatic) watch or the quartz watch that have emerged in more recent times. Therefore, we are returning to the roots and taking a closer look at the history and structure of a mechanical watch in this article.

A mechanical watch is defined by its beating heart: the movement, which is housed in the case. The mechanical movement is made up of numerous components. Among other things, it is equipped with either a manual winding system or an automatic winding system with an oscillating weight. For watches with a manual winding system, a spring is wound ‘by hand’ or ‘manually’ by turning the crown at the side of the watch case. All of the watch’s functions depend on the mainspring, which stores the energy required in the movement and gradually releases it to keep the watch ticking. To ensure this, the watch must be wound at regular intervals. Winding the watch also helps to maintain its ability to keep time accurately.

The oscillating weight of this skeletonised Cartier Santos-Dumont is miniaturised and resembles Alberto Santos-Dumont’s aircraft, the Demoiselle.

Of course, this is a fairly surface-level description of a mechanical watch, but – naturally – it will not suffice for a watch enthusiast. After all, there is still a lot to explore, both historically and technically. To understand how the mechanical watch came about and how it developed, let’s first dive into its history. We will then take a closer look at the mechanical aspects of a wristwatch. In order to provide you with a digestible yet informative overview, we will solely focus on the essentials.

Nowadays, all time measurement tools are just a click or a turn away. In the early days of timekeeping, however, nature served as the only point of reference. Around 5,000 years ago, sundials based on shadows were already in use. Based on the sun’s position, one could determine time through the corresponding shadow cast on a circular division of units. Nevertheless, this method also bore disadvantages: its accuracy depended heavily on the weather and light conditions.

A portable, horizontal sundial made of silver with an integrated compass, before 1681.

Credit © Metmuseum

From the third millennium BC onwards, water clocks provided a solution to these problems. Proven by artefacts from Mesopotamia and Egypt, time was measured by observing the time intervals of the water’s inflow or outflow in containers. Eventually, these water clocks evolved into more sophisticated and increasingly complex time measuring devices using hydraulic and mechanical cogwheel constructions.

A water clock with a baboon decoration from Egypt, ca. 664-30 BC.

Credit © Metmuseum

In the 13th century, this gave rise to mechanical clocks in Europe. They offered a certain independence from environmental influences and relied on an interplay of cogwheels, escapement, and rolling weights as the driving force. This development can primarily be attributed to churches and monasteries. Initially used as table clocks in monasteries, mechanical clocks were soon integrated into church towers, putting time display into the limelight and making it a public affair. Time was often signaled acoustically via chimes or visually indicated through hands moving on a time scale. These acoustic mechanisms were later on used in pocket watches, also named minute repeaters or chiming watches, to provide time indication at night.

In 1360, the municipality of Siena had a mechanical clock installed in the Torre del Mangia, which meant that there was no longer any need for a bell ringer to announce the time with loud chimes throughout the city.

Credit © Mateus Campos Felipe

While hourglasses enjoyed great popularity in the 14th century, innovations were driven forward in the field of mechanical clocks, such as the verge escapement. It enabled a higher degree of accuracy (precise time indication) by pausing the movement while simultaneously transmitting energy. In the 15th century, a new winding system materialized. A tension spring became the more precise option to set the clock mechanism in motion instead of weights. Although its exact inventor is uncertain, the mainspring made the production of small clocks possible in the first place. In contrast to the previously used weight-based winding system, it could be manufactured as a miniature energy store. Thus, the mechanical movement ‘s miniaturisation made the creation of portable clocks possible. In 1462, the term ‘pocket watch’ initially appeared in an Italian correspondence.

A cylindrical table clock by the English clockmaker Bartholomew Newsam with a travelling case, ca. 1580-85.

Credit © Metmuseum

In the course of the 16th century, cylindrical or egg-shaped clocks, that could be carried around, were manufactured. However, they were considerably heavier compared to later pocket watches. It was only from the second half of the century onwards that they started producing these small clocks in shapes that correspond to our modern concept of pocket watches. Moreover, the Swiss watch industry flourished during this period due to a jewellery ban imposed by the influential theologian and reformer John Calvin. To this day, Switzerland remains strongly shaped by the watchmaking industry.

Small mechanical watches were worn on a chain around the neck or in the pocket. The latter wearing method became particularly popular when the English King Charles II. made the waistcoat fashionable. Until around 1680, these watches only had one hand (single-hand watch).

A travelling clock with alarm function by the British clockmaker Thomas Tompion and the case and dial maker Nathaniel Delander is an early example of a clock with the balance spring, which had only just been invented, around 1680.

Credit © Metmuseum

Although tower clocks could already be equipped with a minute hand by then, the necessary miniaturisation had to be refined to achieve a precise minute display for the pocket watches. Besides the minute display for pocket watches, other interesting developments came into being during this period. For example, glass was used to protect watches, and Christiaan Huygens created the balance spring based on the principle of a pendulum.

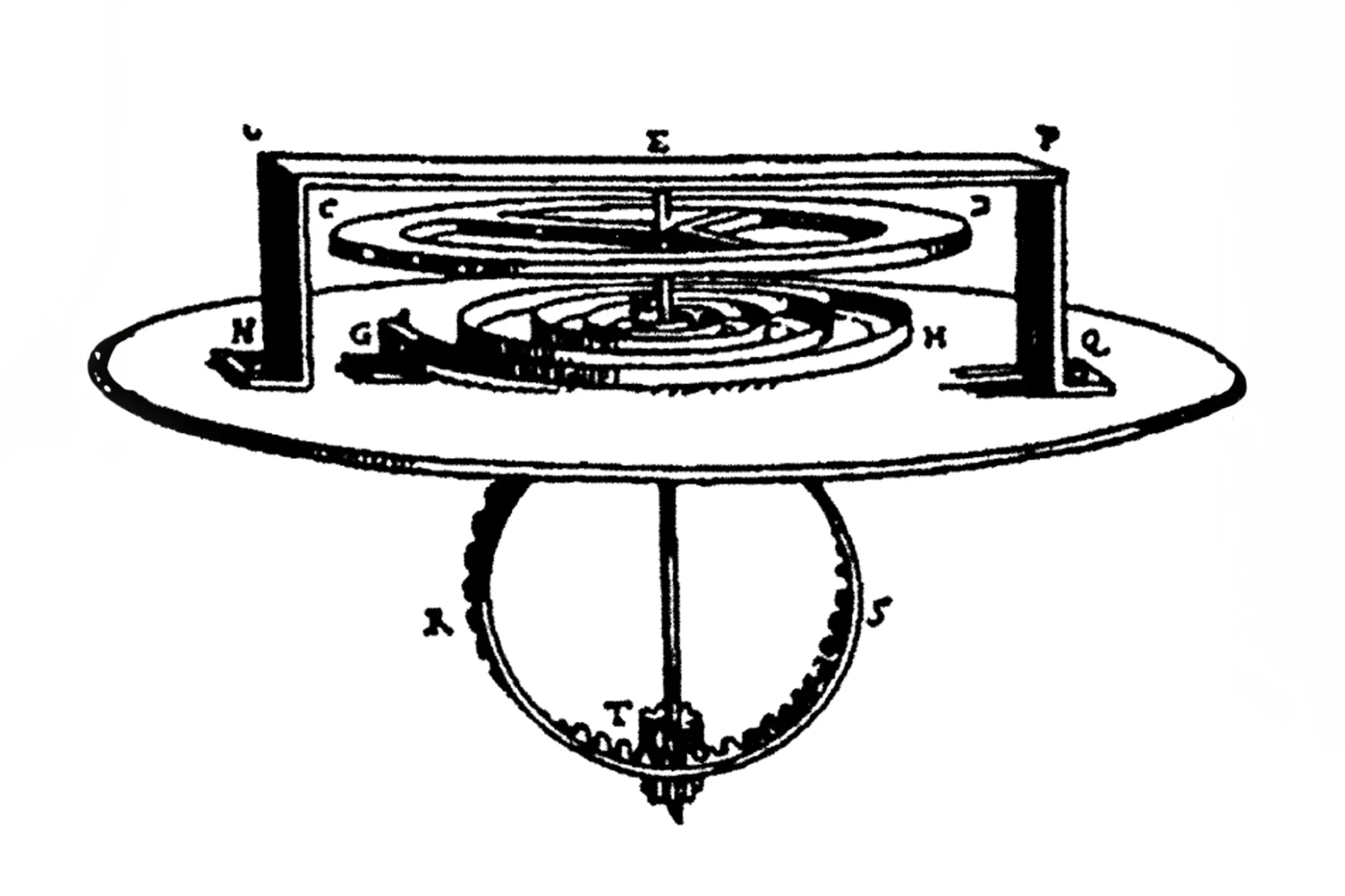

Christiaan Huygens’ balance spring, 1675.

Credit © Fondation Haute Horlogerie

In the 18th century, portable timepieces showcased craftsmanship in all its glory with elaborately decorated surfaces such as gemstone settings, engravings and enamels. Due to their labour-intensive and time-consuming manufacture, pocket watches were not a product for the average citizen and were considered a status symbol, especially among the aristocracy.

A gilt metal and enamel pocket watch by Marwick, Markham and Recordon, circa 1740-60.

Credit © Metmuseum

Another important stage in the development of mechanical watches was achieved by the Englishman Thomas Mudge. He invented the lever escapement in 1755, which is still used in watchmaking today. It improves rate accuracy by transmitting more even impulses to the balance than the previous verge mechanisms.

Nowadays, watches come in all sizes, shapes, and colours. The wristwatch is particularly present in our everyday lives. Its status as an object of daily use and an accessory, however, is no coincidence but the result of centuries of development.

An American banjo-style wall clock, developed by Lemuel Curtis between 1811 and 1816 and produced in collaboration with Joseph Nye Dunning.

Credit © Metmuseum

By the 19th century, there were all kinds of clocks – from church clocks and wall clocks to table clocks and travel clocks. The stopwatch and the time stamp clock were invented in that same century, while the mechanical alarm clock was patented – but the wristwatch had yet to be invented. The first timepiece of its kind was created by Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1810 for the Queen of Naples, and other such creations were to follow.

By the end of the century, these watches had established themselves primarily as luxury jewellery watches for women, not least because they were not particularly accurate. In 1880, the first series of such timepieces for men went into production as custom-made wristwatches by Girard-Perregaux for naval officers. These 2,000 pieces, commissioned by Wilhelm I, are also an example of the general shift from small batches to mass production during this period of industrialisation.

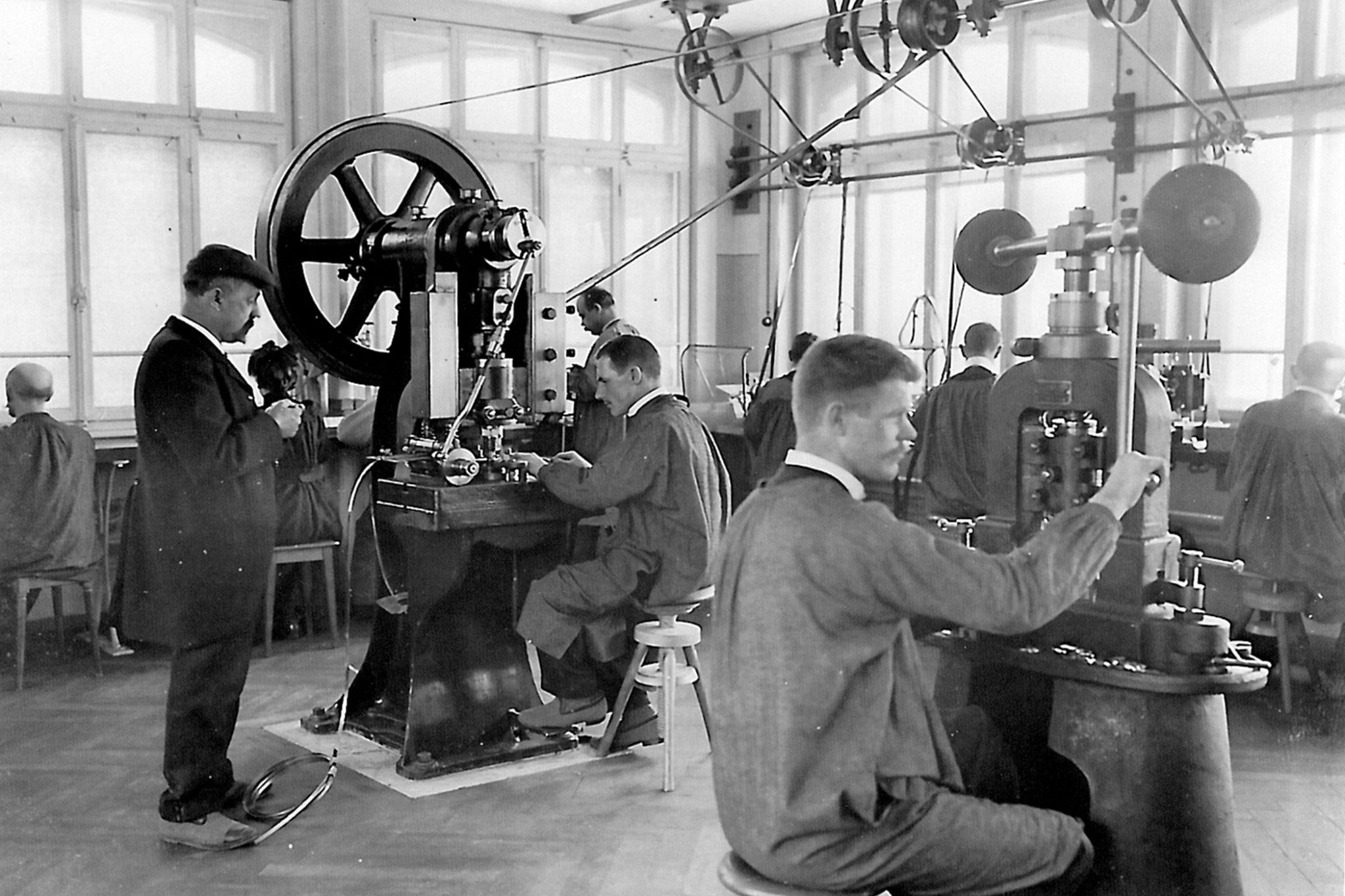

The workshop of the Alpina Union Horlogère S.A. (‘Swiss Watchmakers’ Co-operative’) at the end of the 19th century.

The 20th century saw both moments of success and serious setbacks for mechanical watches. For instance, Louis Cartier and aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont popularised the wristwatch in 1904 with the Santos watch. Thus, the pilot’s watch was conceived, and the wristwatch was no longer regarded as a mere piece of jewellery, but as a useful companion. Many soldiers sported wristwatches during the First World War as they were much more practical than the pocket watches that had been the standard until then.

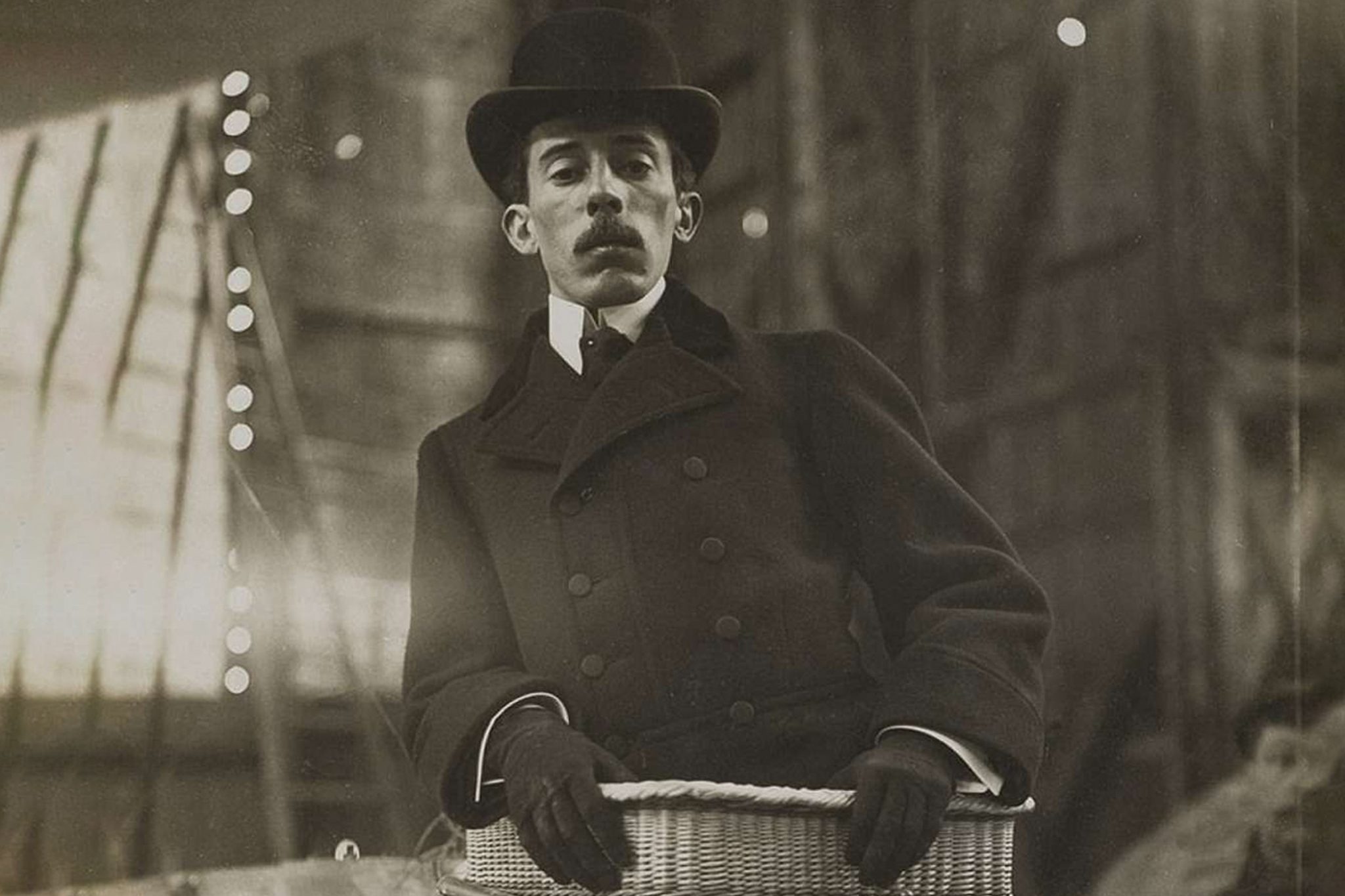

Alberto Santos-Dumont (left) and a Santos-Dumont with a brown leather strap from 1912 (right).

In the 1920s, several innovations were introduced that have continued to influence the world of watchmaking to this day. For example, in 1923 the Briton John Harwood built the first automatic watch and in 1926, Rolex presented the first waterproof wristwatch with its Oyster model.

The Rolex Oyster case, 1926.

Credit © Rolex/Ulysse Frechelin

Perhaps the most significant was the battery-powered quartz watch, invented by Americans Horton and Morrison in 1927. Their invention was to cause a crisis in the watch industry in the 1960s and 1970s, sparked by Seiko’s launch of the first quartz wristwatch in 1969, following the popularity of wristwatches as a product for the broad public in the 1950s and the rise of professional tool watches like the Rolex Submariner or Blancpain Fifty Fathoms in the 1950s and 1960s. Quartz watches, with their analogue or digital time display, are more accurate and their production is significantly easier and cheaper compared to mechanical watches. Ultimately, these advantages thus led to an increased popularity and manufacturing that severely affected many watchmaking companies – especially in Switzerland – economically. Mechanical watchmaking almost came to a standstill, with many businesses downsizing or going bankrupt.

In December 1969, Seiko launched the Quartz Astron 35SQ, the first quartz wristwatch.

Credit © Seiko

It took some time for the industry to recover. Finally, mechanical watches made a big comeback as luxury timepieces in the 1990s. The return to hand-crafted timepieces with elaborate decorations and sophisticated movements clearly set these watches apart from their mass-produced counterparts. Their aesthetics and mechanics, both inside and outside the case, bear witness to the beauty of craftsmanship and the long, innovative history of timekeeping. It is for this precise reason that Swisswatches Magazine deliberately and exclusively focuses on hand-wound and self-winding (automatic) watches. Now, let us take a closer look at the particularities of the two types of mechanical watches.

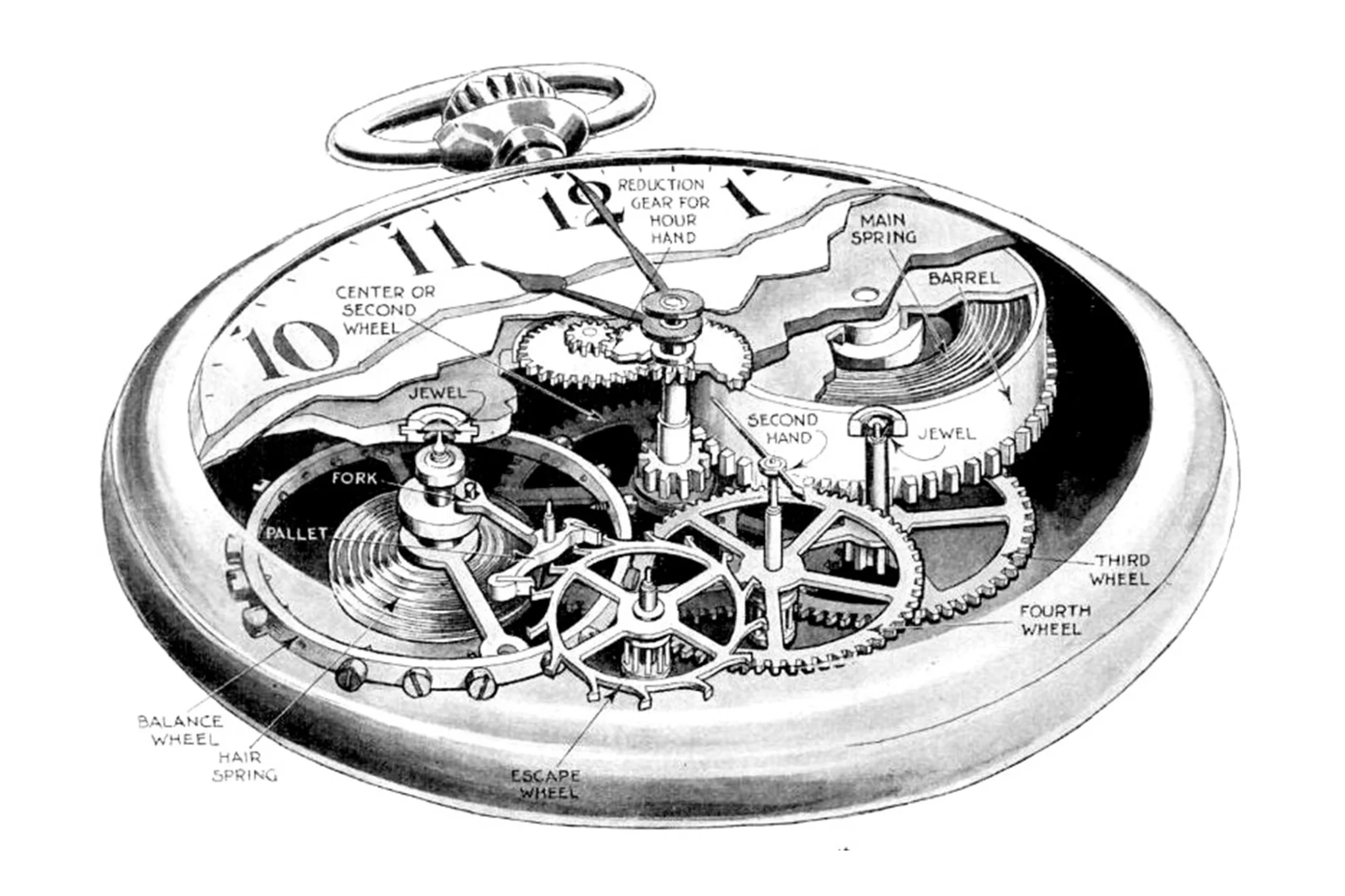

Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak Offshore was launched in 1993 and polarised the world with its oversized bezel.

The anatomy of a mechanical watch is largely made up of springs, gears, pinions, movement plates, and bridges. All components must work in perfect harmony in order for the watch to be accurate. As mentioned at the beginning, the basis of every mechanical watch is the mainspring and the winding mechanism. However, these are only two of the six components of a simple mechanical movement for telling the time via hands and without any additional functions, so-called small or large complications. The other components are the gear train, the escapement, the balance, and the motion works.

Bearing jewels are used in components of a Zenith movement.

They are all integrated into or rest upon the mainplate. Jewel bearings and lubricants are used to ensure that all components work together with as little friction as possible. Originally, precious stones such as garnet, sapphire, or ruby were used as jewel bearings and can still be found in high-quality movements today, although synthetic stones made of aluminium oxide are usually used nowadays.

The mainspring is wrapped tightly in the barrel, a circular box that ensures that the mainspring retains its (now S-shaped) shape and is protected from dust particles. When wound, the mainspring stores energy for the movement and provides the necessary kinetic energy to drive the gear train. While it slowly unwinds, it sets the mainspring barrel in motion, which in turn transfers energy to the balance wheel and thus regulates the movement as a whole.

Here, the mainspring barrel is carefully mounted in an A. Lange und Söhne movement.

The amount of time a watch will run without winding is dependent on the length of the mainspring and the general wear and tear of the watch. For instance, an automatic watch will continue to run if worn regularly, even if it is off the wrist. The storage capacity, known as the power reserve, is at least 40 hours for mechanical watches. Thanks to the spiral shape of the mainspring, even more hours are possible. An empty power reserve means that the spring is loose and needs to be rewound.

The crown is used to set the time and wind the watch. Usually located on the right side of the case, it activates a mechanism consisting of a crown wheel and a ratchet wheel, which transfers energy to the spring and winds it up. The winding stem, winding wheels, and ratchet wheel are all involved in this process. The latter has an influence on the mainspring barrel and, together with a spring and the ratchet, it is responsible for storing the energy as the mainspring is wound via the arbor in the mainspring barrel. A ratchet mechanism ensures that the mainspring train is not inadvertently overwound through too many turns.

The mechanical movement of the Breguet Classique Double Tourbillon “Quai de l’Horloge” 5345.

All the mechanisms described here refer to hand-wound watches but there are also self-winding watches, so-called automatic watches. We will discuss them in more detail later on.

The gear train, also known as the wheel train, transfers energy between the mainspring barrel and escapement. It consists of interlinked cogwheels and pinions (smaller cogwheels with fewer teeth), whose rotational speed is determined by the size and number of teeth. The three essential cogwheels are the minute wheel (which is attached to the mainspring barrel), the third wheel and the fourth wheel (which rotates once a minute). They regulate the oscillations of the seconds, minutes and hours, and the rotation of the hands.

Credit © B. G. Seielstad, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As the number of revolutions increases from the minute wheel via the third wheel to the fourth wheel, the torque decreases. The minute and second wheels both rotate clockwise. The third wheel, on the other hand, transmits the energy and balances the directions and revolution speed. Depending on whether it is a small second (decentralised display) or a central second (hand in the centre of the movement), the arrangement of the wheels is slightly different.

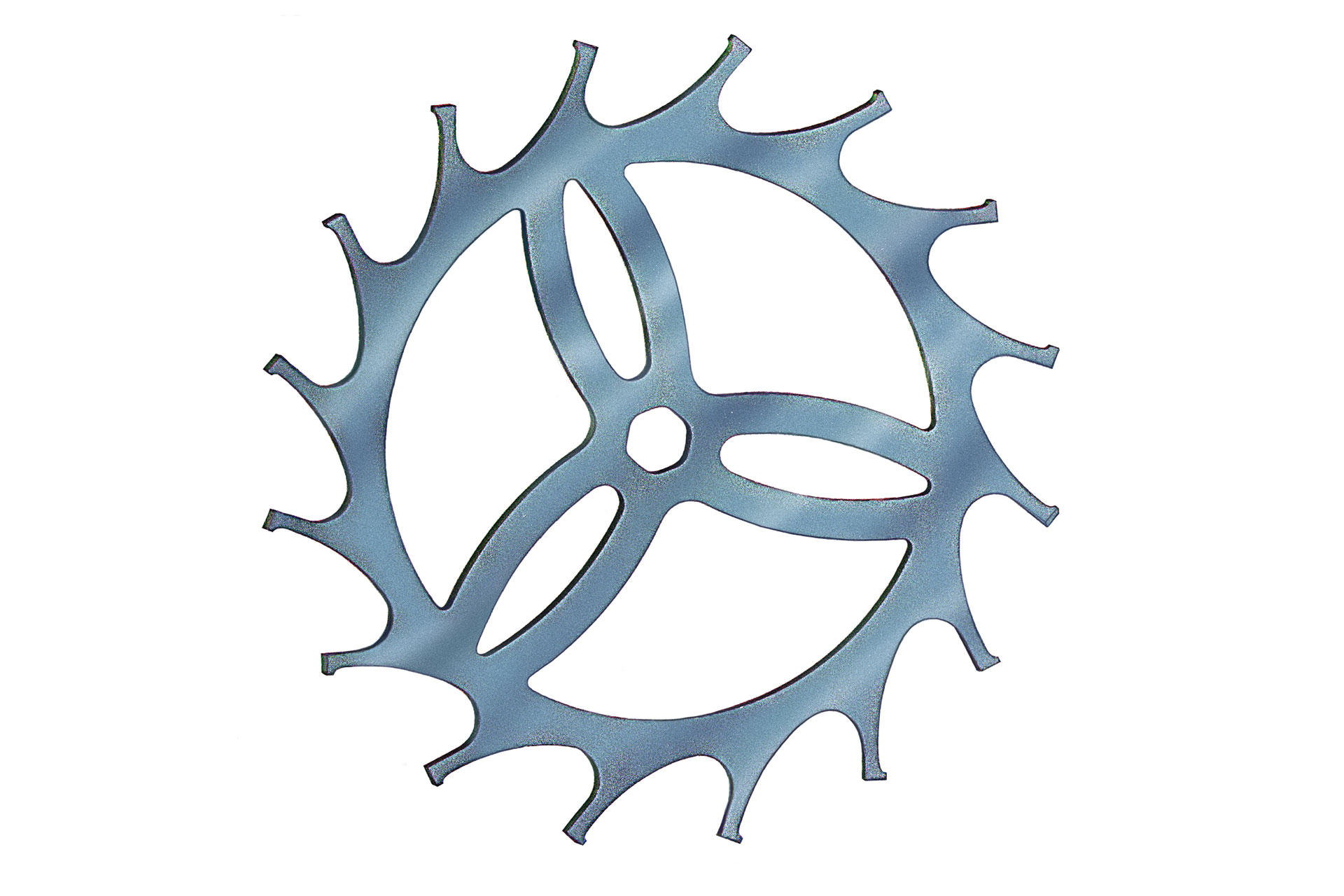

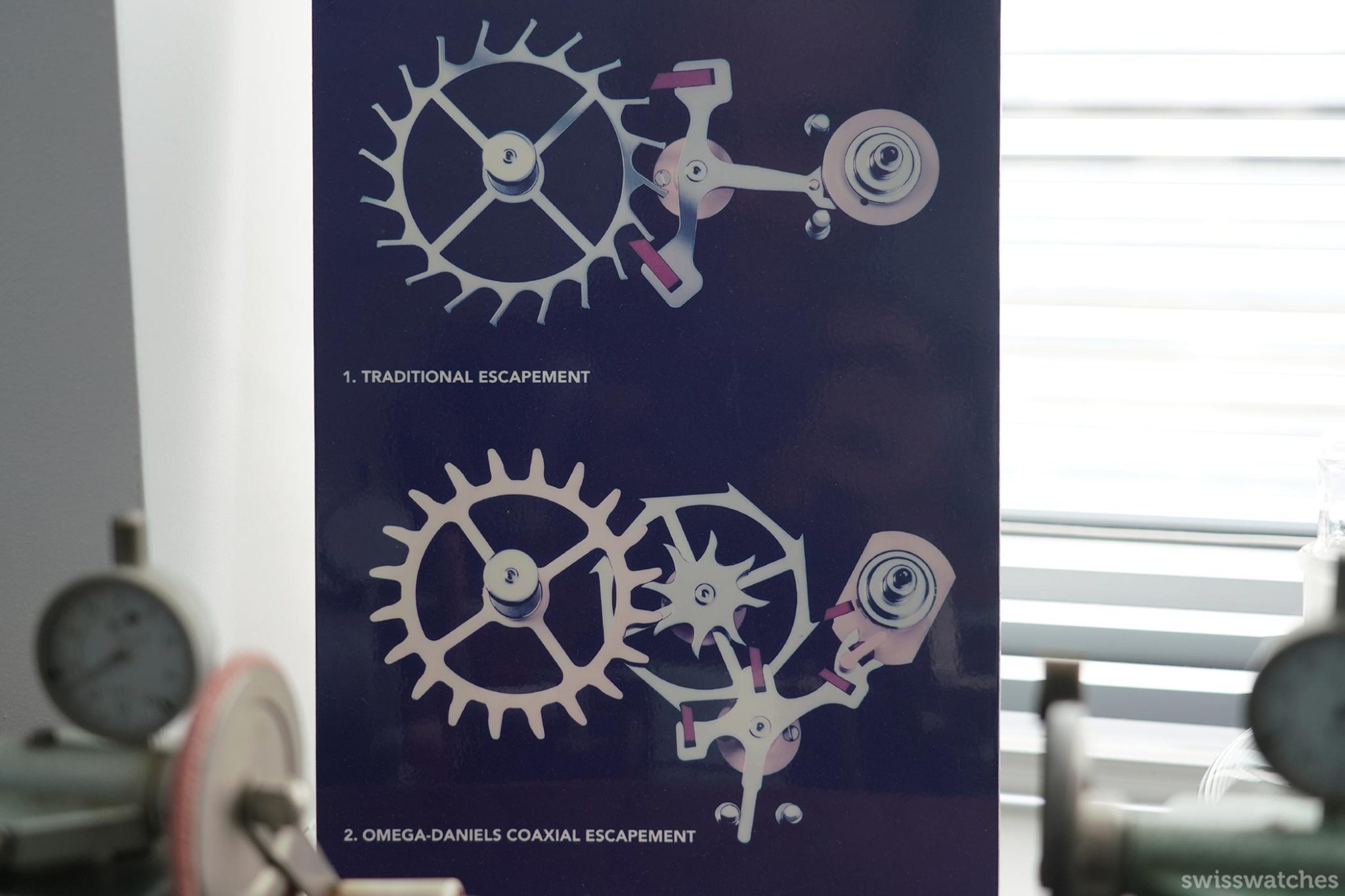

An escapement is vital to ensure that the mainspring releases its energy evenly, without depleting its reserves, and that the movement runs smoothly. The escapement regulates and synchronises the balance wheel, which is important for the accuracy and therefore the correct time indication. It consists of the escape wheel and the anchor.

An escape wheel made of Silizium Silinvar by Patek Philippe.

The former is shaped differently from the other wheels and its movements controlled by the anchor, which swings back and forth. This blocks and releases the escape wheel in time, which also influences the balance in the same way.

A Chronergy escapement from Rolex with escape wheel (left) and anchor (right).

Credit © Rolex/Ulysse Frechelin

Another important moment in horological history was the invention of the co-axial escapement by George Daniels in 1967, patented in 1980. One of the few such innovations of modern times, the co-axial escapement is a modification of the traditional lever escapement that functions using three pallets in order to avoid the sliding friction of a lever escapement. This was revolutionary in the sense that it removed the need for lubrication.

A comparison between the traditional lever escapement and George Daniel’s invention (left) and the Omega De Ville Trésor Power Reserve with coaxial escapement (right).

The balance wheel is necessary to maintain the precision of the movement’s time display. Together with the escapement, it forms the watch’s oscillation system and produces the watch’s characteristic ticking sound. This is because of its movements which set the pace for the pallet fork. The higher the number of oscillations, the faster the watch ticks.

A balance wheel is added to an Akrivia movement.

Here too, the mechanism consists of a wheel that is powered by a small, wafer-thin spiral spring. It is often made of special alloys to withstand temperature fluctuations and magnetic influences.

Time can be indicated through the use of either discs and jumping numbers or of hands. The latter is the more common variant and requires a motion works which is located below the dial.

The Van Cleef & Arpels’ Pierre Arpels Heure d’Ici & Heure d’Ailleurs is an example of a contemporary clock with jumping hours, in which the hours are indicated by numerical discs.

Pulling out the crown allows for a safe setting of the hands, separating the hands from the gear train until the hands have been adjusted and the crown has been pushed back in. The minute wheel moves the minute hand with one revolution per hour. A change wheel is interlocked with the minute wheel and slows it down enough to set the hour hand into motion. The change wheel completes one revolution every 12 hours. Last but not least, the second wheel powers the second hand.

The movement of this Jaeger-LeCoultre watch with hour and minute hands is clearly visible.

With the motion works, we have now completed our brief exploration of the six most important components of a simple mechanical watch with hands. With this foundation, we can now look one step further.

Of course, there are more complicated mechanical watches in addition to the simple ones. They have additional mechanisms whose components are integrated into the basic movement and are powered by the minute wheel or hand movement. These more complex mechanisms are divided into small and large complications, depending on their complexity, although the latter term is not universally clearly defined. Small complications include the second hand or a date, day of the week, or moonphase display. Grand complications such as a tourbillion, chronograph, perpetual calendar or repeaters (striking mechanisms) – or even all of these in combination – are even more elaborate.

The Duometre model from Jaeger-LeCoultre with two movements, heliotourbillon and perpetual calendar.

So far, we have taken a closer look at the mechanical watch with manual winding, but what how does a self-winding watch work? The so-called automatic watch is based on the classic mechanical watch as we have come to know it. It could be regarded as an extension of mechanical manually wound watches.

The first attempts at self-winding mechanisms were made in the 18th century, for example by the Belgian Hubert Sarton. Many of the development stages in the invention of the self-winding watch are not precisely documented, making it impossible to attribute them exactly. It was only with the invention of the wristwatch in the 20th century that the mechanism really came into use because, unlike pocket watches, the necessary energy could be generated through the wrist movement. In 1923, the British watchmaker John Harwood applied for the first patent for an automatic mechanism for wristwatches in Switzerland and was granted it a year later. Finally, a few years later, he began to manufacture these watches in series.

John Harwood’s watch with automatic winding from series production, from 1929 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 47-3543).

Credit © Museumsfoto, CC BY 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1931, the launch of the self-winding Rolex Oyster Perpetual with its sealed case brought success to the mechanism. These models even withstood the quartz crisis with their bidirectional winding system and ball bearings. Today, they still make up an important part of the revered brand’s portfolio.

A rare Rolex Oyster Perpetual Bubbleback in 18-carat gold, circa 1931.

Credit © Archive

The basic components correspond to a manually wound watch. However, in an automatic watch, the mainspring is not wound manually via the crown, but via a rotor. This semi-circular metal piece absorbs the energy transferred to the mainspring through wrist movements and stores it. Therefore, the rotor is naturally also called ‘oscillating weight’, because it nowadays rotates bidirectionally and at a 360° angle, winding up the mainspring and storing energy.

The calibre 01.01-C with a partially skeletonised oscillating weight (left) is fitted in Chopard’s 41 mm Alpine Eagle three-hand models.

As the rotor takes up more space and usually half of the visible caseback, automatic watches have an increased case height compared to mechanical timepieces. Some brands use space-saving micro-rotors that are not located on the movement and instead are integrated into the movement.

The JCB-003 calibre of the Biver Automatique with a 22-carat gold micro-rotor.

There is also the peripheral rotor, used by Patek Philippe, Carl F. Bucherer, Vacheron Constantin, and Cartier, to name but a few. There, the oscillating weight is mounted on a rail on the mainplate, but outside the movement. This positioning means that the rotor does not obscure the view of the entire movement, but reveals it via the sapphire caseback.

The calibre 2160 of the Overseas Tourbillon High Jewellery includes a peripheral rotor made of 22-carat gold.

Whether you opt for a hand-wound or self-winding model is up to you. In any case, with consistent and professional maintenance, mechanical timepieces can last for decades or even centuries as collector’s items – and this, of course, is part of their enduring appeal.

Apart from its impressive technical construction, a mechanical movement’s appearance often also proves eye-catching. It is not for nothing that many mechanical watches have a sapphire crystal caseback that reveals the movement. In contrast to a quartz watch, a mechanical movement’s numerous components provide a lot of surfaces for various decorations. Thus, many watch manufactures specialise in certain decoration techniques and are actively committed to preserving artisan traditions.

The ornamentally decorated hand-wound calibre 567.2 of the Breguet Classique 7637 Répétition Minutes with minute repeater.

Mechanical watches are therefore not luxury objects merely for the sake of it, but also fascinating cultural objects, characterised by their long cultural and technical history. It is a human story that, as showcased by many of the pioneering wristwatches released over the decades, is far from being told. Thus, purchasing a mechanical watch also sustains a small yet fascinating piece of history and tradition.

The Legacy Machine Perpetual Titan with a reimagined perpetual calendar is a masterful reflection of how watchmakers today combine tradition with innovation and continue to write the history of watchmaking.

ALSO READ OUR ARTICLE ABOUT GMT-WATCHES HERE.